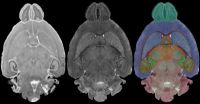

(Press-News.org) DURHAM, N.C. – The most detailed magnetic resonance images ever obtained of a mammalian brain are now available to researchers in a free, online atlas of an ultra-high-resolution mouse brain, thanks to work at the Duke Center for In Vivo Microscopy.

In a typical clinical MRI scan, each pixel in the image represents a cube of tissue, called a voxel, which is typically 1x1x3 millimeters. "The atlas images, however, are more than 300,000 times higher resolution than an MRI scan, with voxels that are 20 micrometers on a side," said G. Allan Johnson, Ph.D., who heads the Duke Center for In Vivo Microscopy and is Charles E. Putman Distinguished Professor of Radiology.

The interactive images in the atlas will allow researchers worldwide to evaluate the brain from all angles and assess and share their mouse studies against this reference brain in genetics, toxicology and drug discovery.

The brain atlas' detail reaches a resolution of 21 microns. A micron is a millionth of a meter, or 0.00003937 of an inch.

An article detailing the creation of the atlas was published as the cover story in the November issue of NeuroImage journal.

The atlas used three different magnetic resonance microscopy protocols of the intact brain followed by conventional histology to highlight different structures in the reference brain. The brains were scanned using an MR system operating at a magnetic field more than 6 times higher than is routinely used in the clinic. The images were acquired on fixed tissues, with the brain in the cranium to avoid the distortion that occurs when tissues are thinly sliced for conventional histology.

The new Waxholm Space brain can be digitally sliced from any plane or angle, so that researchers can precisely visualize any regions in the brain, along any axis without loss of spatial resolution. (Waxholm is the Swedish town where the early concepts gelled for this atlas.)

"Researchers can take the reference brain apart and put it back together, because we have the 3-D data set intact, and any section will have the same excellent resolution," said Johnson, who is also a professor of biomedical engineering and physics at Duke. "It eliminates the Humpty Dumpty problem that researchers used to face when they made 3-D measurements of brain structures."

For example, a geneticist might want to alter a mouse's genotype in an experiment and learn what happens when the animal becomes highly responsive to fear challenges. "It would be interesting to see if the amygdala, (a brain center related to emotional arousal), is really smaller or larger in the animal," Johnson said. "However, if you do conventional histology, the animal brain shrinks when it is dried or prepared in alcohol, sometimes by about 40 percent. Because of variability, that would make it challenging to measure. This atlas provides a reference to measure against."

The team was also able to digitally segment 37 unique brain structures using the three different data acquisition strategies.

Scientists obtained images of brains from eight mice of the most frequently used strain of laboratory mice (C57BL), aged 66-78 days old. They registered the images together and created both an average and a probabilistic brain for reference. The average and probabilistic brains provide quantitative measure of variability. "It was truly remarkable how alike these structures were from brain to brain," he said.

All of the data is available on the web: www.civm.duhs.duke.edu/neuro201001.

As new data is gathered from other sources, researchers will be able to register it to the same coordinate system, which will promote data sharing, Johnson said. For example the Duke group has recently added data – also at the highest resolution yet attained – that allows definition of fiber tracts connecting different parts of the brain. Investigators at the Allen Brain Institute are now using the MR data to provide 3-D location for their extensive gene expression studies (http://mouse.brain-map.org).

INFORMATION:

The project was supported by the National Center for Research Resources, and the National Cancer Institute Small Animal Imaging Resource Program, the Mouse Biomedical Informatics Research Network, and the International Neuroinformatics Coordinating Facility.

Co-authors include Alexandra Badea, Jeffrey Brandenburg, Gary Cofer, and Boma Fubara of the Duke Center for In Vivo Microscopy, and senior author Jonathan Nissanov and Song Liu of the Department of Neurobiology and Anatomy at Drexel University College of Medicine in Philadelphia. Dr. Nissanov is also with the Department of Basic Sciences at Touro University Nevada in Henderson, Nev.

Mouse brain seen in sharpest detail ever

2010-10-26

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Penn study identifies molecular guardian of cell's RNA

2010-10-26

PHILADELPHIA - When most genes are transcribed, the nascent RNAs they produce are not quite ready to be translated into proteins - they have to be processed first. One of those processes is called splicing, a mechanism by which non-coding gene sequences are removed and the remaining protein-coding sequences are joined together to form a final, mature messenger RNA (mRNA), which contains the recipe for making a protein.

For years, researchers have understood the roles played by the molecular machines that carry out the splicing process. But, as it turns out, one of those ...

UI study investigates variability in men's recall of sexual cues

2010-10-26

Even if a woman is perfectly clear in expressing sexual interest or rejection, young men vary in their ability to remember the cues, a new University of Iowa study shows.

Overall, college-age men were quite good at recalling whether their female peers – in this case, represented through photos – showed interest. Their memories were especially sharp if the model happened to be good looking, dressed more provocatively, and conveyed interest through an inviting expression or posture.

But as researchers examined variations in sexual-cue recall, they found two noteworthy ...

Genetic markers offer new clues about how malaria mosquitoes evade eradication

2010-10-26

VIDEO:

Boston College DeLuca Professor of Biology Marc A.T. Muskavitch discusses his latest malaria research, published in the journal Science. Muskavitch and an international team of researchers developed the first high-resolution...

Click here for more information.

CHESTNUT HILL, Mass. (10/25/2010) – The development and first use of a high-density SNP array for the malaria vector mosquito have established 400,000 genetic markers capable of revealing new insights into how ...

Microwave oven key to self-assembly process meeting semi-conductor industry need

2010-10-26

Thanks to a microwave oven, the fundamental nanotechnology process of self assembly may soon replace the lithographic processing use to make the ubiquitous semi-conductor chips. By using microwaves, researchers at Canada's National Institute for Nanotechnology (NINT) and the University of Alberta have dramatically decreased the cooking time for a specific molecular self-assembly process used to assemble block copolymers, and have now made it a viable alternative to the conventional lithography process for use in patterning semi-conductors. When the team of chemists and ...

Heat acclimation benefits athletic performance

2010-10-26

Turning up the heat might be the best thing for athletes competing in cool weather, according to a new study by human physiology researchers at the University of Oregon.

Published in the October issue of the Journal of Applied Physiology, the paper examined the impact of heat acclimation to improve athletic performance in hot and cool environments.

Researchers conducted exercise tests on 12 highly trained cyclists -- 10 males and two females -- before and after a 10-day heat acclimation program. Participants underwent physiological and performance tests under both ...

Unexpected findings of lead exposure may lead to treating blindness

2010-10-26

HOUSTON, Oct. 25, 2010 – Some unexpected effects of lead exposure that may one day help prevent and reverse blindness have been uncovered by a University of Houston (UH) professor and his team.

Donald A. Fox, a professor of vision sciences in UH's College of Optometry (UHCO), described his team's findings in a paper titled "Low-Level Gestational Lead Exposure Increases Retinal Progenitor Cell Proliferation and Rod Photoreceptor and Bipolar Cell Neurogenesis in Mice," published recently online in Environmental Health Perspectives and soon to be published in the print ...

Rice hulls a sustainable drainage option for greenhouse growers

2010-10-26

WEST LAFAYETTE, Ind. - Greenhouse plant growers can substitute rice hulls for perlite in their media without the need for an increase in growth regulators, according to a Purdue University study.

Growing media for ornamental plants often consists of a soilless mix of peat and perlite, a processed mineral used to increase drainage. Growers also regularly use plant-growth regulators to ensure consistent and desired plant characteristics such as height to meet market demands. Organic substitutes for perlite like tree bark have proven difficult because they absorb the plant-growth ...

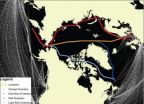

As Arctic warms, increased shipping likely to accelerate climate change

2010-10-26

As the ice-capped Arctic Ocean warms, ship traffic will increase at the top of the world. And if the sea ice continues to decline, a new route connecting international trading partners may emerge -- but not without significant repercussions to climate, according to a U.S. and Canadian research team that includes a University of Delaware scientist.

Growing Arctic ship traffic will bring with it air pollution that has the potential to accelerate climate change in the world's northern reaches. And it's more than a greenhouse gas problem -- engine exhaust particles could ...

UF research gives clues about carbon dioxide patterns at end of Ice Age

2010-10-26

GAINESVILLE, Fla. — New University of Florida research puts to rest the mystery of where old carbon was stored during the last glacial period. It turns out it ended up in the icy waters of the Southern Ocean near Antarctica.

The findings have implications for modern-day global warming, said Ellen Martin, a UF geological sciences professor and an author of the paper, which is published in this week's journal Nature Geoscience.

"It helps us understand how the carbon cycle works, which is important for understanding future global warming scenarios," she said. "Ultimately, ...

Purdue-led research team finds Haiti quake caused by unknown fault

2010-10-26

WEST LAFAYETTE, Ind. - Researchers found a previously unmapped fault was responsible for the devastating Jan. 12 earthquake in Haiti and that the originally blamed fault remains ready to produce a large earthquake.

Eric Calais, a Purdue University professor of earth and atmospheric sciences, led the team that was the first on the ground in Haiti after the magnitude 7.0 earthquake, which killed more than 200,000 people and left 1.5 million homeless.

The team determined the earthquake's origin is a previously unmapped fault, which they named the LÄogëne fault. The newly ...