(Press-News.org) LA JOLLA, CA----Ever find yourself racking your brain on a Monday morning to remember where you put your car keys?

When you do find those keys, you can thank the hippocampus, a brain region responsible for storing and retrieving memories of different environments-such as that room where your keys were hiding in an unusual spot.

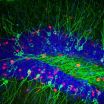

Now, scientists at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies have helped explain how the brain keeps track of the incredibly rich and complex environments people navigate on a daily basis. They discovered how the dentate gyrus, a subregion of the hippocampus, helps keep memories of similar events and environments separate, a finding they reported March 20 in eLife. The findings, which clarify how the brain stores and distinguishes between memories, may also help identify how neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer's disease, rob people of these abilities.

"Everyday, we have to remember subtle differences between how things are today, versus how they were yesterday - from where we parked our car to where we left our cellphone," says Fred H. Gage, senior author on the paper and the Vi and John Adler Chair for Research on Age-Related Neurodegenerative Disease at Salk. "We found how the brain makes these distinctions, by storing separate 'recordings' of each environment in the dentate gyrus."

The process of taking complex memories and converting them into representations that are less easily confused is known as pattern separation. Computational models of brain function suggest that the dentate gyrus helps us perform pattern separation of memories by activating different groups of neurons when an animal is in different environments.

However, previous laboratory studies found that in fact the same populations of neurons in the dentate gyrus are active in different environments, and that the way the cells distinguished new surroundings was by changing the rate at which they sent electrical impulses. This discrepancy between theoretical predictions and laboratory findings has perplexed neuroscientists and obscured our understanding of memory formation and retrieval.

To explore this mystery more deeply, the Salk scientists compared the functioning of the mouse dentate gyrus and another region of the hippocampus, known as CA1, using laboratory techniques for tracking the activity of neurons at multiple time points.

First, the researchers took mice from their original chamber and placed them in a novel chamber to learn about a new environment (episode 1). Meanwhile, they recorded which hippocampal neurons were active as the animals responded to their new surroundings. Subsequently, the mice were either returned to that same novel chamber to measure memory recall or to a slightly modified chamber to measure discrimination (episode 2). The active neurons in episode 2 were also labeled in order to determine if the neurons activated in episode 1 were used in the same way for recall and for discrimination of small differences between environments.

When the researchers compared the neural activity during the two episodes, they found that the dentate gyrus and CA1 sub-regions functioned differently. In CA1, the same neurons that were active during the initial learning episode were also active when the mice retrieved the memories. In the dentate gyrus, however, distinct groups of cells were active during the learning episodes and retrieval. Also, exposing the mice to two subtly different environments activated two distinct groups of cells in the dentate gyrus.

"This finding supported the predictions of theoretical models that different groups of cells are activated during exposure to similar, but distinct, environments," says Wei Deng, a Salk postdoctoral research and first author on the paper. "This contrasts with the findings of previous laboratory studies, possibly because they looked at different sub-populations of neurons in the dentate gyrus."

The Salk researchers' findings suggest that recalling a memory-such as the location of missing keys-does not always involve reactivation of the same neurons that were active during encoding. More importantly, the results indicate that the dentate gyrus performs pattern separation by using distinct populations of cells to represent similar but non-identical memories.

The findings help clarify the mechanisms that underpin memory formation and shed light on systems that are disrupted by injuries and diseases of the nervous system.

INFORMATION:

Mark Mayford, of Scripps Institute Research Institute, also contributed to the research. The study was supported by the James S. McDonnell Foundation, the Lookout Fund, the Kavli Institute for Brain and Mind, and the National Institutes of Health (Grants: MH-090258, NS-050217, AG-020938).

About the Salk Institute for Biological Studies:

The Salk Institute for Biological Studies is one of the world's preeminent basic research institutions, where internationally renowned faculty probe fundamental life science questions in a unique, collaborative, and creative environment. Focused both on discovery and on mentoring future generations of researchers, Salk scientists make groundbreaking contributions to our understanding of cancer, aging, Alzheimer's, diabetes and infectious diseases by studying neuroscience, genetics, cell and plant biology, and related disciplines.

Faculty achievements have been recognized with numerous honors, including Nobel Prizes and memberships in the National Academy of Sciences. Founded in 1960 by polio vaccine pioneer Jonas Salk, M.D., the Institute is an independent nonprofit organization and architectural landmark.

The neuroscience of finding your lost keys

Salk scientists discover how the brain keeps track of similar but distinct memories

2013-03-21

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Parents should do chores together, study says

2013-03-21

You may have heard of couples that strive for exact equality when it comes to chores, i.e. I scrub a dish, you scrub a dish, I change a diaper, you change a diaper.

But new research finds that keeping score with chores isn't the best path to a high-quality relationship. Instead the data points to two items that should have a permanent place on a father's to-do list:

Do housework alongside your spouse

Spend quality time with the kids

"We found that it didn't matter who did what, but how satisfied people were with the division of labor," said Brigham Young University ...

To forgive or not to forgive: What Josh Hamilton tells us about sports fandom

2013-03-21

In a recently published article in Communication & Sport, Jimmy Sanderson, assistant professor in the Department of Communication Studies at Clemson University, and Elizabeth Emmons, a doctoral student in the College of Communication and Information Sciences at the University of Alabama explore people's willingness to forgive then Texas Rangers player Josh Hamilton after an incident in January 2012.

Hamilton serves as a unique study for fan behavior, as he as arguably generates as much attention as a human interest story as he does for his athletic performance. Hamilton's ...

Tackling issues of sexuality among people with dementia

2013-03-21

Managing the delicate issue of sexual expression amongst people with dementia is the focus of a new education resource produced by Griffith University researcher Dr Cindy Jones.

The first resource of its kind and the subject of funding from the Department of Health and Aging and Queensland Dementia Training and Study Centres (DTSC),

Sexualities and Dementia: Education Resource for Health Professionals is aimed at assisting health professionals working across care settings.

Based on national and international literature and research by Dr Jones from

Griffith's Centre ...

Study reveals potential treatments for Ebola and a range of other deadly viruses

2013-03-21

Illnesses caused by many of the world's most deadly viruses cannot be effectively treated with existing drugs or vaccines. A study published by Cell Press in the March 21 issue of the journal Chemistry & Biology has revealed several compounds that can inhibit multiple viruses, such as highly lethal Ebola virus, as well as pathogens responsible for rabies, mumps, and measles, opening up new therapeutic avenues for combating highly pathogenic viruses.

"The medical field currently does not have ideal antiviral therapies, often no therapeutics at all, and the development ...

Harnessing immune cells' adaptability to design an effective HIV vaccine

2013-03-21

In infected individuals, HIV mutates rapidly to escape recognition by immune cells. This process of continuous evolution is the main obstacle to natural immunity and the development of an effective vaccine. A new study published by Cell Press in the March 21 issue of the journal Immunity reveals that the immune system has the capacity to adapt such that it can recognize mutations in HIV. The findings suggest that our immune cells' adaptability could be harnessed to help in the fight against AIDS.

An international collaboration between research groups in France, England, ...

Functional characteristics of antitumor T cells change w increasing time after therapeutic transfer

2013-03-21

PHILADELPHIA — Scientists have characterized how the functionality of genetically engineered T cells administered therapeutically to patients with melanoma changed over time. The data, which are published in Cancer Discovery, a journal of the American Association for Cancer Research, highlight the need for new strategies to sustain antitumor T cell functionality to increase the effectiveness of this immunotherapeutic approach.

Early clinical research has indicated that cell-based immunotherapies for cancer, in particular melanoma, have potential because patients treated ...

Adults worldwide eat almost double daily AHA recommended amount of sodium

2013-03-21

Seventy-five percent of the world's population consumes nearly twice the daily recommended amount of sodium (salt), according to research presented at the American Heart Association's Nutrition, Physical Activity and Metabolism and Cardiovascular Disease Epidemiology and Prevention 2013 Scientific Sessions.

Global sodium intake from commercially prepared food, table salt, salt and soy sauce added during cooking averaged nearly 4,000 mg a day in 2010.

The World Health Organization recommends limiting sodium to less than 2,000 mg a day and the American Heart Association ...

Japanese researchers identify a protein linked to the exacerbation of COPD

2013-03-21

Researchers from the RIKEN Advanced Science Institute and Nippon Medical School in Japan have identified a protein likely to be involved in the exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). This protein, Siglec-14, could serve as a potential new target for the treatment of COPD exacerbation.

In a study published today in the journal Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences the researchers show that COPD patients who do not express Siglec-14, a glycan-recognition protein, are less susceptible to exacerbation compared with those who do.

COPD is a chronic ...

Scripps Research study underlines potential of new technology to diagnose disease

2013-03-21

JUPITER, FL – March 21, 2013 – Researchers at The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) in Jupiter, FL, have developed cutting-edge technology that can successfully screen human blood for disease markers. This tool may hold the key to better diagnosing and understanding today's most pressing and puzzling health conditions, including autoimmune diseases.

"This study validates that the 'antigen surrogate' technology will indeed be a powerful tool for diagnostics," said Thomas Kodadek, PhD, a professor in the Departments of Chemistry and Cancer Biology and vice chairman of ...

BUSM researchers identify chemical compounds that halt virus replication

2013-03-21

(Boston) – Researchers at Boston University School of Medicine (BUSM) have identified a new chemical class of compounds that have the potential to block genetically diverse viruses from replicating. The findings, published in Chemistry & Biology, could allow for the development of broad-spectrum antiviral medications to treat a number of viruses, including the highly pathogenic Ebola and Marburg viruses.

Claire Marie Filone, PhD, postdoctoral researcher at BUSM and the United States Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases (USAMRIID), is the paper's first ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Alkali cation effects in electrochemical carbon dioxide reduction

Test platforms for charging wireless cars now fit on a bench

$3 million NIH grant funds national study of Medicare Advantage’s benefit expansion into social supports

Amplified Sciences achieves CAP accreditation for cutting-edge diagnostic lab

Fred Hutch announces 12 recipients of the annual Harold M. Weintraub Graduate Student Award

Native forest litter helps rebuild soil life in post-mining landscapes

Mountain soils in arid regions may emit more greenhouse gas as climate shifts, new study finds

Pairing biochar with other soil amendments could unlock stronger gains in soil health

Why do we get a skip in our step when we’re happy? Thank dopamine

UC Irvine scientists uncover cellular mechanism behind muscle repair

Platform to map living brain noninvasively takes next big step

Stress-testing the Cascadia Subduction Zone reveals variability that could impact how earthquakes spread

We may be underestimating the true carbon cost of northern wildfires

Blood test predicts which bladder cancer patients may safely skip surgery

Kennesaw State's Vijay Anand honored as National Academy of Inventors Senior Member

Recovery from whaling reveals the role of age in Humpback reproduction

Can the canny tick help prevent disease like MS and cancer?

Newcomer children show lower rates of emergency department use for non‑urgent conditions, study finds

Cognitive and neuropsychiatric function in former American football players

From trash to climate tech: rubber gloves find new life as carbon capturers materials

A step towards needed treatments for hantaviruses in new molecular map

Boys are more motivated, while girls are more compassionate?

Study identifies opposing roles for IL6 and IL6R in long-term mortality

AI accurately spots medical disorder from privacy-conscious hand images

Transient Pauli blocking for broadband ultrafast optical switching

Political polarization can spur CO2 emissions, stymie climate action

Researchers develop new strategy for improving inverted perovskite solar cells

Yes! The role of YAP and CTGF as potential therapeutic targets for preventing severe liver disease

Pancreatic cancer may begin hiding from the immune system earlier than we thought

Robotic wing inspired by nature delivers leap in underwater stability

[Press-News.org] The neuroscience of finding your lost keysSalk scientists discover how the brain keeps track of similar but distinct memories