(Press-News.org) PASADENA, Calif.—Five years ago, neuroscientist Christof Koch of the California Institute of Technology (Caltech), neurosurgeon Itzhak Fried of UCLA, and their colleagues discovered that a single neuron in the human brain can function much like a sophisticated computer and recognize people, landmarks, and objects, suggesting that a consistent and explicit code may help transform complex visual representations into long-term and more abstract memories.

Now Koch and Fried, along with former Caltech graduate student and current postdoctoral fellow Moran Cerf, have found that individuals can exert conscious control over the firing of these single neurons—despite the neurons' location in an area of the brain previously thought inaccessible to conscious control—and, in doing so, manipulate the behavior of an image on a computer screen.

The work, which appears in a paper in the October 28 issue of the journal Nature, shows that "individuals can rapidly, consciously, and voluntarily control neurons deep inside their head," says Koch, the Lois and Victor Troendle Professor of Cognitive and Behavioral Biology and professor of computation and neural systems at Caltech.

The study was conducted on 12 epilepsy patients at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, where Fried directs the Epilepsy Surgery Program. All of the patients suffered from seizures that could not be controlled by medication. To help localize where their seizures were originating in preparation for possible later surgery, the patients were surgically implanted with electrodes deep within the centers of their brains. Cerf used these electrodes to record the activity, as indicated by spikes on a computer screen, of individual neurons in parts of the medial temporal lobe—a brain region that plays a major role in human memory and emotion.

Prior to recording the activity of the neurons, Cerf interviewed each of the patients to learn about their interests. "I wanted to see what they like—say, the band Guns N' Roses, the TV show House, and the Red Sox," he says. Using that information, he created for each patient a data set of around 100 images reflecting the things he or she cares about. The patients then viewed those images, one after another, as Cerf monitored their brain activity to look for the targeted firing of single neurons. "Of 100 pictures, maybe 10 will have a strong correlation to a neuron," he says. "Those images might represent cached memories—things the patient has recently seen."

The four most strongly responding neurons, representing four different images, were selected for further investigation. "The goal was to get patients to control things with their minds," Cerf says. By thinking about the individual images—a picture of Marilyn Monroe, for example—the patients triggered the activity of their corresponding neurons, which was translated first into the movement of a cursor on a computer screen. In this way, patients trained themselves to move that cursor up and down, or even play a computer game.

But, says Cerf, "we wanted to take it one step further than just brain–machine interfaces and tap into the competition for attention between thoughts that race through our mind."

To do that, the team arranged for a situation in which two concepts competed for dominance in the mind of the patient. "We had patients sit in front of a blank screen and asked them to think of one of the target images," Cerf explains. As they thought of the image, and the related neuron fired, "we made the image appear on the screen," he says. That image is the "target." Then one of the other three images is introduced, to serve as the "distractor."

"The patient starts with a 50/50 image, a hybrid, representing the 'marriage' of the two images," Cerf says, and then has to make the target image fade in—just using his or her mind—and the distractor fade out. During the tests, the patients came up with their own personal strategies for making the right images appear; some simply thought of the picture, while others repeated the name of the image out loud or focused their gaze on a particular aspect of the image. Regardless of their tactics, the subjects quickly got the hang of the task, and they were successful in around 70 percent of trials.

"The patients clearly found this task to be incredibly fun as they started to feel that they control things in the environment purely with their thought," says Cerf. "They were highly enthusiastic to try new things and see the boundaries of 'thoughts' that still allow them to activate things in the environment."

Notably, even in cases where the patients were on the verge of failure—with, say, the distractor image representing 90 percent of the composite picture, so that it was essentially all the patients saw—"they were able to pull it back," Cerf says. Imagine, for example, that the target image is Bill Clinton and the distractor George Bush. When the patient is "failing" the task, the George Bush image will dominate. "The patient will see George Bush, but they're supposed to be thinking about Bill Clinton. So they shut off Bush—somehow figuring out how to control the flow of that information in their brain—and make other information appear. The imagery in their brain," he says, "is stronger than the hybrid image on the screen."

According to Koch, what is most exciting "is the discovery that the part of the brain that stores the instruction 'think of Clinton' reaches into the medial temporal lobe and excites the set of neurons responding to Clinton, simultaneously suppressing the population of neurons representing Bush, while leaving the vast majority of cells representing other concepts or familiar person untouched."

INFORMATION:

The work in the paper, "On-line voluntary control of human temporal lobe neurons," is part of a decade-long collaboration between the Fried and Koch groups, funded by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the National Institute of Mental Health, the G. Harold & Leila Y. Mathers Charitable Foundation, and Korea's World Class University program.

Visit the Caltech Media Relations website at http://media.caltech.edu.

Controlling individual cortical nerve cells by human thought

2010-10-28

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Revising the timeline for deadly pancreatic cancer

2010-10-28

Pancreatic tumors are one of the most lethal cancers, with fewer than five percent of patients surviving five years after diagnosis. But a new study that peers deeply into the genetics of pancreatic cancer presents a bit of good news: an opportunity for early diagnosis. In contrast to earlier predictions, many pancreatic tumors are, in fact, slow growing, taking nearly 20 years to become lethal after the first genetic perturbations appear.

"There have been two competing theories explaining why pancreatic cancers are so lethal," says Bert Vogelstein, the Howard Hughes ...

1000 Genomes Project publishes analysis of completed pilot phase

2010-10-28

Small genetic differences between individuals help explain why some people have a higher risk than others for developing illnesses such as diabetes or cancer. Today in the journal Nature, the 1000 Genomes Project, an international public-private consortium, published the most comprehensive map of these genetic differences, called variations, estimated to contain approximately 95 percent of the genetic variation of any person on Earth.

Researchers produced the map using next-generation DNA sequencing technologies to systematically characterize human genetic variation ...

Large-scale fish farm production offsets environmental gains

2010-10-28

VICTORIA – Industrial-scale aquaculture production magnifies environmental degradation, according to the first global assessment of the effects of marine finfish aquaculture (e.g. salmon, cod, turbot and grouper) released today. This is true even when farming operations implement the best current marine fish farming practices.

Dr. John Volpe and his team at the University of Victoria developed the Global Aquaculture Performance Index (GAPI), an unprecedented system for objectively measuring the environmental performance of fish farming.

"Scale is critical," said Dr. ...

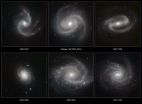

Spiral galaxies stripped bare

2010-10-28

HAWK-I [1] is one of the newest and most powerful cameras on ESO's Very Large Telescope (VLT). It is sensitive to infrared light, which means that much of the obscuring dust in the galaxies' spiral arms becomes transparent to its detectors. Compared to the earlier, and still much-used, VLT infrared camera ISAAC, HAWK-I has sixteen times as many pixels to cover a much larger area of sky in one shot and, by using newer technology than ISAAC, it has a greater sensitivity to faint infrared radiation [2]. Because HAWK-I can study galaxies stripped bare of the confusing effects ...

Singapore scientist leads team to discover origin of brain immune cells

2010-10-28

A team of international scientists led by Dr Florent Ginhoux of the Singapore Immunology Network (SIgN) of Singapore's Agency of Science, Technology and Research (A*STAR), have made a breakthrough that could lead to a better understanding of many neurodegenerative and inflammatory brain disorders. Their work, published in top scientific journal Science, uncovered the origins of microglia, which are white blood cells specific to the brain, and showed that, in mice, microglia had a completely different origin than other white blood cells. This understanding may lead to the ...

Narcotics and diagnostics overused in treatment of chronic neck pain

2010-10-28

Duke University and University of North Carolina (UNC) researchers report in the November issue of Arthritis Care & Research that narcotics and diagnostic testing are overused in treating chronic neck pain. Their findings indicate clinicians may overlook more effective treatments for neck pain, such as therapeutic exercise. According to reviews cited in the study, evidence to support the effectiveness of therapeutic exercise in treating chronic neck pain is good, yet only 53% of subjects were prescribed such exercise. This information was based upon reported data from a ...

Learning the truth not effective in battling rumors about NYC mosque, study finds

2010-10-28

COLUMBUS, Ohio – Evidence is no match against the belief in false rumors concerning the proposed Islamic cultural center and mosque near Ground Zero in New York City, a new study finds.

Researchers at Ohio State University found that fewer than one-third of people who had previously heard and believed one of the many rumors about the proposed center changed their minds after reading overwhelming evidence rejecting the rumor.

The false rumor that researchers used in the study was that Feisal Abdul Rauf, the Imam backing the proposed Islamic cultural center and mosque, ...

Victims of child abuse present higher rates of post-traumatic stress disorder

2010-10-28

In cases of child sexual abuse, there are children and teenagers that blame themselves (for example, after the thought that the abuse was led by them) or their family (thinking that their family should have protected them) for the abuse suffered in their childhood. This type of victims resort more frequently to avoidance coping. Thus, they try to sleep more than usual, avoid thinking on the problem, or resort to alcohol and drug abuse –in the case of teenagers. This behaviour leaves important psychological after-effects on victims: concretely, they present more symptoms ...

Introducing the 'A-Train'

2010-10-28

Mention the "A-Train" and most people probably think of the jazz legend Billy Strayhorn or perhaps New York City subway trains — not climate change. However, it turns out that a convoy of "A-Train" satellites has emerged as one of the most powerful tools scientists have for understanding our planet's changing climate.

The formation of satellites — which currently includes Aqua, CloudSat, Cloud-Aerosol Lidar and Infrared Pathfinder Satellite Observations (CALIPSO) and Aura satellites — barrels across the equator each day at around 1:30 p.m. local time each afternoon, giving ...

Glucosamine causes the death of pancreatic cells

2010-10-28

Quebec City, October 27, 2010—High doses or prolonged use of glucosamine causes the death of pancreatic cells and could increase the risk of developing diabetes, according to a team of researchers at Université Laval's Faculty of Pharmacy. Details of this discovery were recently published on the website of the Journal of Endocrinology.

In vitro tests conducted by Professor Frédéric Picard and his team revealed that glucosamine exposure causes a significant increase in mortality in insulin-producing pancreatic cells, a phenomenon tied to the development of diabetes. Cell ...