(Press-News.org) An international collaboration led by research groups from Mainz and Darmstadt, Germany, has achieved the synthesis of a new class of chemical compounds for superheavy elements at the RIKEN Nishina Center for Accelerator-based Research (RNC) in Japan. For the first time, a chemical bond was established between a superheavy element – seaborgium (element 106) in the present study – and a carbon atom. Eighteen atoms of seaborgium were converted into seaborgium hexacarbonyl complexes, which include six carbon monoxide molecules bound to the seaborgium. Its gaseous properties and adsorption to a silicon dioxide surface were studied, and compared with similar compounds of neighbors of seaborgium in the same group of the periodic table. The study opens perspectives for much more detailed investigations of the chemical behavior of elements at the end of the periodic table, where the influence of effects of relativity on chemical properties is most pronounced.

Chemical experiments with superheavy elements – with atomic number beyond 104 – are most challenging: First, the very element to be studied has to be artificially created using a particle accelerator. Maximum production rates are on the order of a few atoms per day at most, and are even less for the heavier ones. Second, the atoms decay quickly through radioactive processes – in the present case within about 10 seconds, adding to the experiment's complexity. A strong motivation for such demanding studies is that the very many positively charged protons inside the atomic nuclei accelerate electrons in the atom's shells to very high velocities – about 80 percent of the speed of light. According to Einstein's theory of relativity, the electrons become heavier than they are at rest. Consequently, their orbits may differ from those of corresponding electrons in lighter elements, where the electrons are much slower. Such effects are expected to be best seen by comparing properties of so-called homologue elements, which have a similar structure in their electronic shell and stand in the same group in the periodic table. This way, fundamental underpinnings of the periodic table of the elements – the standard elemental ordering scheme for chemists all around the world – can be probed.

Chemical studies with superheavy elements often focus on compounds, which are gaseous already at comparatively low temperatures. This allows their rapid transport in the gas phase, benefitting a fast process as needed in light of the short lifetimes. To date, compounds containing halogens and oxygen have often been selected; as an example, seaborgium was studied previously in a compound with two chlorine and two oxygen atoms – a very stable compound with high volatility. However, in such compounds, all of the outermost electrons are occupied in covalent chemical bonds, which may mask relativistic effects. The search for more advanced systems, involving compounds with different bonding properties that exhibit effects of relativity more clearly, continued for many years.

In the preparation for the current work, the superheavy element chemistry groups at the Institute for Nuclear Chemistry at Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz (JGU), the Helmholtz Institute Mainz (HIM), and the GSI Helmholtz Center for Heavy Ion Research (GSI) in Darmstadt together with Swiss colleagues from the Paul Scherrer Institute, Villigen, and the University of Berne developed a new approach, which promised to allow chemical studies with single, short-lived atoms also for compounds which were less stable. Initial tests were carried out at the TRIGA Mainz research reactor and were shown to work exceptionally well with short-lived atoms of molybdenum. The method was elaborated at Berne University and in accelerator experiments at GSI. Dr. Alexander Yakushev from the GSI team explains: "A big challenge in such experiments is the intense accelerator beam, which destroys even moderately stable chemical compounds. To overcome this problem, we first sent tungsten, the heavier neighbor of molybdenum, through a magnetic separator and separated it from the beam. Chemical experiments were then performed behind the separator, where conditions are ideal to study also new compound classes." The focus was on the formation of hexacarbonyl complexes. Theoretical studies starting in the 1990s predicted these to be rather stable. Seaborgium is bound to six carbon monoxide molecules through metal-carbon bonds, in a way typical of organometallic compounds, many of which exhibit the desired electronic bond situation the superheavy element chemists were dreaming of for long.

The Superheavy Element Group at the RNC in Wako, Japan, optimized the seaborgium production in the fusion process of a neon beam (element 10) with a curium target (element 96) and isolated it in the GAs-filled Recoil Ion Separator (GARIS). Dr. Hiromitsu Haba, team leader at RIKEN, explains: "In the conventional technique for producing superheavy elements, large amounts of byproducts often disturb the detection of single atoms of superheavy elements such as seaborgium. Using the GARIS separator, we were able at last to catch the signals of seaborgium and evaluate its production rates and decay properties. With GARIS, seaborgium became ready for next-generation chemical studies."

In 2013, the two groups teamed up, together with colleagues from Switzerland, Japan, the United States, and China, to study whether they could synthesize a superheavy element compound like seaborgium hexacarbonyl. In two weeks of round-the-clock experiments, with the German chemistry setup coupled to the Japanese GARIS separator, 18 seaborgium atoms were detected. The gaseous properties as well as the adsorption on a silicon dioxide surface were studied and found to be similar to those of the corresponding hexacarbonyls of the homologs molybdenum and tungsten – very characteristic compounds of the group-6 elements in the periodic table – adding proof to the identity of the seaborgium hexacarbonyl. The measured properties were in agreement with theoretical calculations, in which the effects of relativity were included.

Dr. Hideto En'yo, the director of RNC says: "This breakthrough experiment could not have succeeded without the powerful and tight collaboration between fourteen institutes around the world." Prof. Frank Maas, the director of the HIM, says "The experiment represents a milestone in chemical studies of superheavy elements, showing that many advanced compounds are within reach of experimental investigation. The perspectives that this opens up for gaining more insight into the nature of chemical bonds, not only in superheavy elements, are fascinating."

Following this first successful step along the path to more detailed studies of the superheavy elements, the team already has plans for further studies of yet other compounds, and with even heavier elements than seaborgium. Soon, Einstein may have to show the deck in his hand with which he twists the chemical properties of elements at the end of the periodic table.

INFORMATION:

Publication:

Julia Even et al.

Synthesis and detection of a seaborgium carbonyl complex

Science, 18 September 2014

DOI: 10.1126/science.1255720

Images:

http://www.uni-mainz.de/bilder_presse/09_kernchemie_seaborgium_01.jpg

Dr. Julia Even from the Helmholtz Institute in Mainz, Germany, and Dr. Hiromitsu Haba from RIKEN, Wako, Japan, prepare the GARIS gas-filled recoil separator (top right) for connection to the Recoil Transfer Chamber chemistry interface (bottom center).

photo: Matthias Schädel

http://www.uni-mainz.de/bilder_presse/09_kernchemie_seaborgium_02.jpg

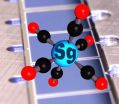

Graphic representation of a seaborgium hexacarbonyl molecule on the silicon dioxide covered detectors of a COMPACT detector array

ill.: Alexander Yakushev (GSI) / Christoph E. Düllmann (JGU)

Further information:

Professor Dr. Christoph Düllmann

Institute for Nuclear Chemistry

Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz

D 55099 Mainz, GERMANY

phone +49 6131 39-25852

fax +49 6131 39-20811

e-mail: duellmann@uni-mainz.de

http://www.kernchemie.uni-mainz.de/eng/index.php

GSI Helmholtz Centre for Heavy Ion Research

Planckstr. 1

D 64291 Darmstadt, GERMANY

phone +49 6159 71-2462

fax +49 6159 71-3463

e-mail: C.E.Duellmann@gsi.de

https://www.gsi.de/en/start/news.htm

Related link:

http://www.superheavies.de

http://www.sciencemag.org/content/345/6203/1491 (abstract)

Milestone in chemical studies of superheavy elements

Chemical bond between a superheavy element and a carbon atom established for the first time, new vistas for studying effects of Einstein's relativity on the structure of the periodic table

2014-09-19

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Technique to model infections shows why live vaccines may be most effective

2014-09-19

Vaccines against Salmonella that use a live, but weakened, form of the bacteria are more effective than those that use only dead fragments because of the particular way in which they stimulate the immune system, according to research from the University of Cambridge published today in the journal PLOS Pathogens.

The BBSRC-funded researchers used a new technique that they have developed where several populations of bacteria, each of which has been individually tagged with a unique DNA sequence, are administered to the same host (in this case, a mouse). This allows the ...

How pneumonia bacteria can compromise heart health

2014-09-19

Bacterial pneumonia in adults carries an elevated risk for adverse cardiac events (such as heart failure, arrhythmias, and heart attacks) that contribute substantially to mortality—but how the heart is compromised has been unclear. A study published on September 18th in PLOS Pathogens now demonstrates that Streptococcus pneumoniae, the bacterium responsible for most cases of bacterial pneumonia, can invade the heart and cause the death of heart muscle cells.

Carlos Orihuela, from the University of Texas Health Science Center in San Antonio, USA, and colleagues initially ...

Human sense of fairness evolved to favor long-term cooperation

2014-09-19

VIDEO:

This is a video describing the ultimatum game in chimpanzees.

Click here for more information.

ATLANTA—The human response to unfairness evolved in order to support long-term cooperation, according to a research team from Georgia State University and Emory University.

Fairness is a social ideal that cannot be measured, so to understand the evolution of fairness in humans, Dr. Sarah Brosnan of Georgia State's departments of Psychology and Philosophy, the Neuroscience Institute ...

Nuclear spins control current in plastic LED

2014-09-19

SALT LAKE CITY, Sept. 18, 2014 – University of Utah physicists read the subatomic "spins" in the centers or nuclei of hydrogen isotopes, and used the data to control current that powered light in a cheap, plastic LED – at room temperature and without strong magnetic fields.

The study – published in Friday's issue of the journal Science – brings physics a step closer to practical machines that work "spintronically" as well as electronically: superfast quantum computers, more compact data storage devices and plastic or organic light-emitting diodes, or OLEDs, more efficient ...

Changes in coastal upwelling linked to temporary declines in marine ecosystem

2014-09-19

In findings of relevance to both conservationists and the fishing industry, new research links short-term reductions in growth and reproduction of marine animals off the California Coast to increasing variability in the strength of coastal upwelling currents — currents which historically supply nutrients to the region's diverse ecosystem.

Along the west coast of North America, winds lift deep, nutrient-rich water into sunlit surface layers, fueling vast phytoplankton blooms that ultimately support fish, seabirds and marine mammals.

The new study, led by Bryan Black ...

World population to keep growing this century, hit 11 billion by 2100

2014-09-19

Using modern statistical tools, a new study led by the University of Washington and the United Nations finds that world population is likely to keep growing throughout the 21st century. The number of people on Earth is likely to reach 11 billion by 2100, the study concludes, about 2 billion higher than some previous estimates.

The paper published online Sept. 18 in the journal Science includes the most up-to-date estimates for future world population, as well as a new method for creating such estimates.

"The consensus over the past 20 years or so was that world population, ...

Scientists discover 'dimmer switch' for mood disorders

2014-09-19

Researchers at University of California, San Diego School of Medicine have identified a control mechanism for an area of the brain that processes sensory and emotive information that humans experience as "disappointment."

The discovery of what may effectively be a neurochemical antidote for feeling let-down is reported Sept. 18 in the online edition of Science.

"The idea that some people see the world as a glass half empty has a chemical basis in the brain," said senior author Roberto Malinow, MD, PhD, professor in the Department of Neurosciences and neurobiology section ...

Study shows how epigenetic memory is passed across generations

2014-09-19

A growing body of evidence suggests that environmental stresses can cause changes in gene expression that are transmitted from parents to their offspring, making "epigenetics" a hot topic. Epigenetic modifications do not affect the DNA sequence of genes, but change how the DNA is packaged and how genes are expressed. Now, a study by scientists at the University of California, Santa Cruz, shows how epigenetic memory can be passed across generations and from cell to cell during development.

The study, published September 19 in Science, focused on one well studied epigenetic ...

New insights into the world of quantum materials

2014-09-19

This news release is available in German.

How a system behaves is determined by its interaction properties. An important concept in condensed matter physics for describing the energy distribution of electrons in solids is the Fermi surface, named for Italian physicist Enrico Fermi. The existence of the Fermi surface is a direct consequence of the Pauli exclusion principle, which forbids two identical fermions from occupying the same quantum state simultaneously. Energetically, the Fermi surface divides filled energy levels from the empty ones. For electrons and other ...

A more efficient, lightweight and low-cost organic solar cell

2014-09-19

AMHERST, Mass. – For decades, polymer scientists and synthetic chemists working to improve the power conversion efficiency of organic solar cells were hampered by the inherent drawbacks of commonly used metal electrodes, including their instability and susceptibility to oxidation. Now for the first time, researchers at the University of Massachusetts Amherst have developed a more efficient, easily processable and lightweight solar cell that can use virtually any metal for the electrode, effectively breaking the "electrode barrier."

This barrier has been a big problem ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Ambitious model fails to explain near-death experiences, experts say

Multifaceted effects of inward foreign direct investment on new venture creation

Exploring mutations that spontaneously switch on a key brain cell receptor

Two-step genome editing enables the creation of full-length humanized mouse models

Pusan National University researchers develop light-activated tissue adhesive patch for rapid, watertight neurosurgical sealing

Study finds so-called super agers tend to have at least two key genetic advantages

Brain stimulation device cleared for ADHD in the US is overall safe but ineffective

Scientists discover natural ‘brake’ that could stop harmful inflammation

Tougher solid electrolyte advances long-sought lithium metal batteries

Experts provide policy roadmap to reduce dementia risk

New 3D imaging system could address limitations of MRI, CT and ultrasound

First-in-human drug trial lowers high blood fats

Decades of dredging are pushing the Dutch Western Scheldt Estuary beyond its ecological limits

A view into the innermost workings of life: First scanning electron microscope with nanomanipulator inaugurated in hesse at Goethe University

Simple method can enable early detection and prevention of chronic kidney disease

S-species-stimulated deep reconstruction of ultra-homogeneous CuS nanosheets for efficient HMF electrooxidation

Mechanical and corrosion behavior of additively manufactured NiTi shape memory alloys

New discovery rewrites the rules of antigen presentation

Researchers achieve chain-length control of fatty acid biosynthesis in yeast

Water interactions in molecular sieve catalysis: Framework evolution and reaction modulation

Shark biology breakthrough: Study tracks tiger sharks to Maui mating hub

Mysterious iron ‘bar’ discovered in famous nebula

World-first tool reduces harmful engagement with AI-generated explicit images

Learning about public consensus on climate change does little to boost people’s support for action, study shows

Sylvester Cancer Tip Sheet for January 2026

The Global Ocean Ship-Based Hydrographic Investigations Program (GO-SHIP) receives the Ocean Observing Team Award

Elva Escobar Briones selected for The Oceanography Society Mentoring Award

Why a life-threatening sedative is being prescribed more often for seniors

Findings suggest that certain medications for Type 2 diabetes reduce risk of dementia

UC Riverside scientists win 2025 Buchalter Cosmology Prize

[Press-News.org] Milestone in chemical studies of superheavy elementsChemical bond between a superheavy element and a carbon atom established for the first time, new vistas for studying effects of Einstein's relativity on the structure of the periodic table