(Press-News.org) PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — We celebrate our triumphs over adversity, but let's face it: We'd rather not experience difficulty at all. A new study ties that behavioral inclination to learning: When researchers added a bit of conflict to make a learning task more difficult, that additional conflict biased learning by reducing the influence of reward and increasing the influence of aversion to punishment.

This newly found relationship between conflict and reinforcement learning suggests that the circuits in the frontal cortex that calculate the degree of conflict, effort, and difficulty of actions are integrated with the dopamine-driven circuits that govern perceptions of reward and punishment in another part of the brain, the striatum. In two sets of experiments reported in Nature Communications, scientists at Brown University and the University of New Mexico gathered evidence for the link by several means, including EEG scans, genetic tests, manipulation with a low dose of a dopamine-related drug, even tracking eye blinks.

"The signals in the cortex that respond to conflict act to induce an aversive learning signal in your basic reinforcement learning systems," said Brown University cognitive scientist Michael Frank, co-author of the study led by former student James Cavanagh, now an assistant professor at the University of New Mexico.

A Tricky Task

The conflict in the experimental learning was merely a matter of having to use the left hand to indicate the selection of a stimulus on the right side of a screen, or vice versa. This simple case of spatial conflict is well established in cognitive psychology. In this study it slowed responses by only about 12 milliseconds but elicited reliable EEG brain signals typically associated with a conflict-induced "alarm bell."

Here's how the task worked: In a learning phase the 83 volunteer adults simply had to press the left button on a game pad when they saw a blue shape or the right button when they saw a yellow one. There were four shapes in all (call them A, B, C, and D) that could appear on either side of the screen. Each shape had a different probability of providing a one point reward when learners pressed the correct button. A was always rewarded, D was seldom rewarded. B and C were each equivalently rewarded 50 percent of the time, but B never provided a point when it appeared on the side opposite from the button and C's reward occurred only when it appeared on the side opposite from the button.

In this way, punishment (no points) for B became associated with the opposite-side conflict as did C's reward (one point).

After the conflict-infused learning phase, people then moved on to a second phase where they were shown pairs of these previously observed shapes and had to indicate their preferences in terms of which one they thought was more rewarding.

Everyone learned that A was rewarding and D was not, but learned perceptions of B and C were skewed in one of two ways for each participant. For those who learn better from reward, conflict acted to reduce experienced reward value, leading to a preference for B over C. For those who learn better from avoiding punishment, conflict acted to enhanced experienced punishment value, leading to greater avoidance of B. In essence the latter effect is like "adding insult to injury," where conflict made gaining no points even more aversive.

Behavior in the brain

The researchers weren't just relying on behavioral observation to inform their study. The EEG sensors monitored the midcingulate cortex, which previous research identified as the site where the brain determines the costs of effort, difficulty, and conflict in action. The sensors measured the strength of theta and delta frequency brainwaves while people carried out the phases of the task.

"The degree to which conflict reduced reward-related theta/delta activity of C compared with B was related to preferences for B, and the degree to which conflict enhanced punishment related-theta activity of B compared with C was related to avoidance of B," the authors wrote. "These findings suggest that conflict acted to both diminish reward value and to boost punishment avoidance within cortical systems associated with interpreting the salience of feedback."

So how does the cortical conflict signal actually change learning about reward values? The researchers looked to the volunteers' genes, specifically one called DARPP-32, which governs how dopamine is processed in downstream areas of the brain. That's because research has shown that people with some variants of the gene are more sensitive to reward learning, while people with other variants are more sensitive to punishment avoidance learning, consistent with how this gene affects dopamine function in neurons sensitive to rewards and punishments in the striatum.

The genotyping confirmed that whether people became biased in favor of B or C had to do with their genetic predisposition to learn more from reward or avoiding punishment.

In a second set of experiments with 30 volunteers, Cavanagh, Frank, and their co-authors actively manipulated dopamine function in this downstream area (i.e., the striatum). They gave subjects safe, low doses of the drug cabergoline, which temporarily reduces receptivity to dopamine. Prior work had shown that this subtle effect causes people to learn more from punishment avoidance than reward. Sure enough it did. Without the drug (on placebo), volunteers overall slightly favored B over C, but with the drug, that flipped to a significantly greater bias for C over B, consistent with learning from punishment avoidance.

They even observed that that degree to which this drug affected the conflict value learning was related to its effects on eye blink rate, which has been linked to dopamine activity.

Cavanagh said he hopes to apply the knowledge to better understand learning in people with obsessive-compulsive disorder and other anxiety disorders who have enhanced theta band signals of conflict.

"Does it make them learn more from 'punishments,' does it make them learn less from reward?" he said. "What does the consequence of this well-known alteration in anxiety have to do with the way they learn from the world?"

INFORMATION:

In addition to Cavanagh and Frank, other authors are Sean Masters and Kevin Bath of Brown.

The National Science Foundation supported the study (grant 1125788).

HOUSTON – (Nov. 4, 2014) – Rice University scientists who want to gain an edge in energy production and storage report they have found it in molybdenum disulfide.

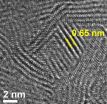

The Rice lab of chemist James Tour has turned molybdenum disulfide's two-dimensional form into a nanoporous film that can catalyze the production of hydrogen or be used for energy storage.

The versatile chemical compound classified as a dichalcogenide is inert along its flat sides, but previous studies determined the material's edges are highly efficient catalysts for hydrogen evolution reaction ...

HOUSTON – (Nov. 4, 2014) – A majority of Madagascar's 101 species of lemurs are threatened with extinction, and that could have serious consequences for the rainforests they call home. A new study by Rice University researchers shows the positive impacts lemurs can have on rainforest tree populations, which raises concerns about the potential impact their disappearance could have on the region's rich biodiversity.

A large proportion of trees in Madagascar's rainforest have fruits eaten by lemurs. Lemurs in turn disperse the seeds of their fruit trees throughout ...

OAK BROOK, Ill. – Researchers using coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA) have found a close association between high-risk coronary artery plaque and a common liver disease. The study, published online in the journal Radiology, found that a single CT exam can detect both conditions.

Previous research has shown that CCTA can detect high-risk coronary artery plaque, or plaque prone to life-threatening ruptures. For the new study, researchers looked at associations between high-risk plaque and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), a condition characterized ...

Over eighty percent of breast cancer patients in the United States use complementary therapies following a breast cancer diagnosis, but there has been little science-based guidance to inform clinicians and patients about their safety and effectiveness. In newly published guidelines from the Society for Integrative Oncology, researchers at Columbia University's Mailman School of Public Health and the Herbert Irving Comprehensive Cancer Center with colleagues at MD Anderson Cancer Center, University of Michigan, Memorial Sloan Kettering, and other institutions in the U.S. ...

PHILADELPHIA - Two new studies from the Abramson Cancer Center and the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania offer hope for breast cancer survivors struggling with cancer-related pain and swelling, and point to ways to enhance muscular strength and body image. The studies appear in a first of its kind monograph from the Journal of the National Cancer Institute Monographs focusing on integrative oncology, which combines a variety of therapies, some non-traditional, for maximum benefit to cancer patients.

In the first study, A Hybrid Effectiveness-Implementation ...

Chestnut Hill, MA (November 4, 2014): Whether it's politics in the United States or violent conflict in the Mideast, the roots of the vitriol and intractability begin to grow not from a hatred of the other side, but from a misunderstanding of what's motivating the other side. According to a new study co-authored by a Boston College neuroscientist, not only does this misunderstanding pose a barrier to solutions, but it can be corrected through financial incentives.

The research involved the participation of almost 3,000 people: Israelis and Palestinians in the Mideast, ...

Over half the smokers using the Liverpool Stop Smoking Service have tried electronic cigarettes (51.3 per cent). Of these, nearly half had used them within the past month and are considered current users (45.5 per cent).

The data* – presented at the National Cancer Research Institute (NCRI) Cancer Conference in Liverpool today (Tuesday) – also highlights that smokers are more likely to try e-cigarettes if they feel more confident that the products are safer than tobacco smoking.

Researchers from the University of Liverpool quizzed more than 320 smokers from ...

Swallowing a sponge on a string could replace traditional endoscopy as an equally effective but less invasive way of diagnosing a condition that can be a forerunner of oesophageal cancer.

The results of a Cancer Research UK trial involving more than 1,000 people are being presented today (Tuesday) at the National Cancer Research Institute's annual conference in Liverpool.

The trial invited more than 600 patients with Barrett's Oesophagus – a condition that can sometimes lead to oesophageal cancer – to swallow the Cytosponge and to undergo an endoscopy. ...

Shift work, like chronic jet lag, is known to disrupt the body's internal clock (circadian rhythms), and it has been linked to a range of health problems, such as ulcers, cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome, and some cancers.

But little is known about its potential impact on brain function, such as memory and processing speed.

The researchers therefore tracked the cognitive abilities of more than 3000 people who were either working in a wide range of sectors or who had retired, at three time points: 1996; 2001; and 2006.

Just under half (1484) of the sample, ...

Around one in five patients with chest pain will have no obvious signs of coronary artery disease after investigation, and their symptoms are unlikely to have a physical cause.

But it is not always clear who these patients are, and they often undergo extensive and expensive tests to find out that nothing is wrong with their hearts.

The German authors therefore wanted to test the prevalence of physical and mental symptoms in 253 patients who had been investigated for chest pain/shortness of breath/palpitations and found to have no coronary artery disease.

The type ...