Working to unravel the complex wiring system that underlies this intense physiological state, investigators at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK), part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), have identified a long-sought component of this complicated neural network.

Described online today in Nature Neuroscience, the team has found that a melanoncortin 4 receptor-regulated (MC4R) circuit serves as the neural link that inhibits and controls eating. Their discovery shows that this brain circuit not only promotes fullness in hungry mice but also removes the almost painful sensation of grating hunger, findings that could provide a promising new target for the development of weight-loss drugs.

The Roots of Hunger

Hunger ensures survival by signaling to the body that energy reserves are low and food is needed to avoid starvation. "One reason that dieting is so difficult is because of the unpleasant sensation arising from a persistent hunger drive," explains the study's co-senior author Bradford Lowell, MD, PhD, an investigator in BIDMC'S Center for Nutrition and Metabolism and Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School. "Our results show that the artificial activation of this particular brain circuit is pleasurable and can reduce feeding in mice, essentially resulting in the same outcome as dieting but without the chronic feeling of hunger."

The Lowell laboratory has spent the last two decades creating a wiring diagram of the complex neurocircuitry that underscores hunger, feeding and appetite. Their group, along with others, made the key discovery that Agouti-peptide-expressing (AgRP) neurons, a small group of neurons located in the brain's hypothalamus, detect caloric deficiency and drive intense feeding.

"When these AgRP neurons are 'turned on,' either by fasting or by artificial means, laboratory animals eat voraciously," says Lowell. What's happening, he explains, is that AgRP neurons sense the low energy reserves, become activated, and through the release of inhibitory neurotransmitters, suppress the activity of downstream neurons, which are responsible for feelings of fullness, or satiety. This causes hunger.

But to understand exactly how the brain regulates appetite, the researchers needed to determine which neurons were downstream of the AgRP neurons and were actually causing the activation and inhibition of hunger.

"Determining the identity of these 'satiety' neurons is the key to establishing the blueprint for how the brain can regulate appetite," says Lowell. "It was an important missing point of connection in the wiring diagram."

The Search for Satiety Neurons

Because AgRP hunger neurons release the AgRP peptide which is known to block melanocortin 4 receptors, Lowell and co-corresponding authors Michael Krashes, PhD, and Alastair Garfield, PhD, hypothesized that these downstream satiety neurons must have many MC4Rs.

"Our previous work had revealed that out of all the millions of neurons in the brain, this tiny group of MC4R-expressing neurons in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus [PVH] were important for the regulation of feeding behavior and body weight," explains Lowell. With this in mind the authors set about mapping and then manipulating the activity of these PVH MC4R neurons and then observing the feeding behavior of the mice.

In order to gain direct access to these MC4R neurons from within the daunting tangle of neurocircuits, the authors used a group of genetically engineered mice that selectively express the Cre-recombinase protein in these particular brain cells; this enabled the scientists to map their connections and remotely control their activity.

Led by Garfield, a visiting fellow in the Lowell laboratory from the Centre for Integrative Physiology at the University of Edinburgh, the authors employed a chemogenetic technique known as DREADDs (Designer Receptor Exclusively Activated by Designer Drugs) to specifically and selectively control the activity of these PVH MC4R neurons in the Cre recombinase mice.

"Although these mice had eaten a day's worth of calories and were fully sated, when we used DREADDS to turn off the PVH MC4R cells they began to ravenously consume food for which they had no caloric need," says Garfield. He adds that the opposite also held true: artificially activating these satiety neurons prevented unfed hungry mice from eating. "Together these experiments suggested that PVH MC4R neurons function like a brake on feeding and are essential to prevent overeating," says Garfield.

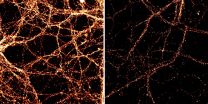

Much like an electronic circuit board, the brain is made up of discrete nodes connected by intricate wiring. After the authors determined that the PVH MC4 cells controlled satiety, says Garfield, the next logical step was to identify the downstream node in the circuit that was mediating this effect. By injecting a tracer molecule into the PVH MC4R neurons they were able to visualize the cells in other areas of the brain that were communicating with these cells. Their experiment revealed dense innervation of an area in the back of the brain called the lateral parabrachial nucleus (LPBN).

To probe the importance of this circuit in regulating appetite the scientists used optigenetics, a technology enabling them to selectively activate the subset of PVH MC4R neurons that target the LPBN by delivering blue laser light via a glass optical fiber implanted in the brains of the mice. As predicted, in the hungry mice, laser activation of this explicit PVH MC4R - LPBN circuit engaged a "brake" that significantly reduced the animals' food consumption.

Confirming the Drive Reduction Theory

"There is a major hypothesis called 'Drive Reduction' that proposes that you eat to get rid of the unpleasant feeling of hunger," explains Lowell. "This is in contrast to other views that propose that you eat because the taste of good food is rewarding. We, therefore, needed to conduct a behavioral experiment that would tell us whether this PVH MC4R - LPBN circuit, which mice normally activate by eating, would be pleasant if activated artificially, in the absence of any food being consumed."

To answer this question, co-senior author Michael Krashes and his colleagues at the NIDDK developed a sophisticated behavioral experiment in which laser stimulation served as a surrogate for eating food. The experiment also enabled the mice to control the activation of their PVH MC4R - LPBN circuit based on their spatial location.

"We built a two-chamber apparatus separated by a doorway through which the hungry animals were free to move back and forth, as we tracked their activity," explains Krashes. "If the animal moved into one chamber, computer software triggered the delivery of the blue laser light, which stimulated the animal's PVH MC4R - LPBN brain circuit. But when the animal returned to the other chamber, the laser switched off and the circuit was no longer stimulated."

The scientists followed the mice for 25 minutes to determine in which chamber the animals preferred to spend time. "Normal mice displayed no preference for either chamber," says Krashes, "but the genetically engineered mice [which were able to stimulate the brain's PVH MC4R - LPBN circuit] greatly preferred the blue light-associated chamber, highlighting the gratifying sensation that took away their bad feelings of hunger."

Remarkably, explains Krashes, when this experiment was repeated in mice that had recently eaten a meal (and therefore were not experiencing the negative feelings of hunger), turning on the satiety-promoting PVH MC4R - LPBN circuit lost its positive value, and the animals no longer showed a preference for the light-paired chamber.

"If the animals had found food in one particular chamber, then we expect that they would have stayed in that chamber and would have eaten, but since there was no food, they found another way of achieving the same result by self-stimulating the satiety-promoting PVH MC4R - LPBN circuit," Krashes explains.

"Turning on the PVH-MC4R satiety neurons had the same effect as dieting but because it directly reduced hunger drive it did not cause the gnawing feelings of discomfort that often come with dieting," says Lowell. "Our findings suggest that the therapeutic targeting of these cells may reduce both food consumption and the aversive sensations of hunger - and therefore may be an effective treatment for obesity."

INFORMATION:

In addition to Lowell, Krashes and Garfield, coauthors include Chia Li and Joseph Madara (co-first authors), Bhavik P Shah, Emily Webber, Jennifer S. Steger, John N. Campbell, Oksana Gavrilova, Charlotte E. Lee, David P. Olson, Joel K. Elmquist and Bakhos A. Tannous.

This work was supported in part by the Boston Area Diabetes Endocrinology Research Center; the University of Edinburgh Chancellor's Fellowship; US National Institutes of Health grants (R01DK096010, R01DK089044, R01DK071051, R01DK075632; R37DK053477, BNORC Transgenic Core P30DK046200, BADERC Transgenic Core P30DK057521, F32DK089710; K08DK0671561; and R01 DK088423; R37 DK0053301) and an American Diabetes Association Mentor-Based Fellowship. This research was also supported, in part, by the Intramural Research Program of the NIDDK, NIH (1ZIADK075087, 1ZIADK075088).

Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center is a patient care, teaching and research affiliate of Harvard Medical School and consistently ranks as a national leader among independent hospitals in National Institutes of Health funding.

BIDMC is in the community with Beth Israel Deaconess Hospital-Milton, Beth Israel Deaconess Hospital-Needham, Beth Israel Deaconess Hospital-Plymouth, Anna Jaques Hospital, Cambridge Health Alliance, Lawrence General Hospital, Signature Healthcare, Beth Israel Deaconess HealthCare, Community Care Alliance and Atrius Health. BIDMC is also clinically affiliated with the Joslin Diabetes Center and Hebrew Senior Life and is a research partner of Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center and The Jackson Laboratory. BIDMC is the official hospital of the Boston Red Sox. For more information, visit http://www.bidmc.org.

The content of this press release is the sole responsibility of its authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIH.