Researchers at the University of Michigan Medical School have started to answer these questions by studying the microbiome of the lungs - the community of microscopic organisms are in constant contact with our respiratory system.

By studying these bacterial communities, and how they change in illness, they hope to pave the way for new ways to prevent and fight lung infections in patients.

Speaking the same language

In new findings reported in recent weeks, the U-M team has shown that a nasty "feedback loop" could explain the explosive onset of bacterial lung infections: The growth of certain bacteria is accelerated by the very molecules that our body's cells make as distress signals.

The study, published in the American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, was the first to ask how levels of these "distress signals" relate to bacterial communities in the lungs. These stress molecules, called catecholamines (such as adrenaline), together make up one of the body's primary ways of responding to stress or injury. Previous laboratory studies have found that some bacteria grow faster when exposed to these molecules, but no human or animal study has determined if they are related to changes in the respiratory microbiome.

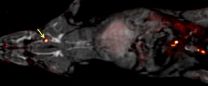

Using 40 samples taken from lung transplant patients in various states of health, the U-M team found that the community of bacteria in the lungs had collapsed in those with respiratory infections, and that this collapse was strongly associated with levels of catecholamines in the lung. The most common bacteria found in these collapsed communities were the ones that respond to catecholamines in laboratory experiments.

"Our findings suggest that the human and bacterial cells in our lungs are speaking the same language," says Robert Dickson, M.D., an assistant professor of internal medicine and the lead author of several of the new papers. "Our lung's immune cells respond to infection by making catecholamines. Our findings suggest that these catecholamines can in turn make certain dangerous bacteria grow faster, which causes more inflammation and stress signaling. It's a vicious cycle."

Dickson notes that understanding of the lung microbiome is still in its infancy, and the field is often overshadowed by the microbiome of the digestive tract.

In fact, many medical textbooks still teach that the lungs are free of bacteria, with microscopic organisms only present during infections. Meanwhile, in recent years research on the vast numbers of microbes living in our guts has blossomed.

But research led by Dickson and U-M microbiologist Gary Huffnagle, Ph.D., continues to show that, though our lungs aren't nearly as filled with microbes as our digestive tracts, the "ecosystem" of the lung microbiome is thriving and important.

"The lungs have their own anatomy, their own physiology, and their own ecology," says Dickson. "The rules from the gut microbiome may not apply. We need to start thinking about how pneumonia and other lung diseases emerge from the complex ecosystem of our respiratory tract."

In a recent paper in PLoS Pathogens, the U-M team lays out key principles for understanding the ecology of the lung microbiome and its role in disease.

Antarctica or Madagascar?

In another recent paper, published in the Annals of the American Thoracic Society, the U-M team asked how alike the bacterial communities in various areas of the lungs are in healthy individuals. The work sprang from an observation in patients with advanced lung disease: the bacterial communities found in one region of a patient's lungs can look entirely different from communities found elsewhere in the lungs of the same patient.

"Since the inside of our lungs has a surface area that's 30 times as big as our skin, it's not surprising to see some variation in bacteria," says Dickson. "But no one had looked to see how spatially varied these bacterial communities are in healthy people."

So the team, led by Jeffrey Curtis, M.D., obtained specimens of lung bacterial communities from multiple sites in the lungs of 15 healthy research volunteers. They studied them in detail using advanced genetic sequencing that makes it possible to see the relative numbers of different microbes in the population of a particular area. They found that healthy people have relatively uniform bacterial populations throughout their lungs, and the microbiome differs much more from person to person than within a single person's lungs.

These findings support the "adapted island model" that the U-M team has developed to explain how the lung microbiome is populated in healthy individuals. In this model, the lungs are constantly seeded by bacteria from the "source community" of the mouth, just as islands are seeded by immigration of species from nearby continents.

"The lungs aren't chock full of bacteria like the digestive tract, but they're not free of them either," says Dickson. He likens the healthy lung microbiome to the human population of Antarctica. "People move in, people move out, but there's not a whole lot of reproduction going on."

But in people with damaged lungs - such as those with cystic fibrosis or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease - the ecosystem is much more hospitable for bacteria. The lungs and airways become more like a tropical rainforest, rich in food and nutrients, where certain bacteria can thrive and reproduce - more like Madagascar than Antarctica.

Healthy vs. diseased

In a paper last year in The Lancet, Dickson and Huffnagle reviewed what's known about exacerbations - flare-ups of diseases such as asthma, CF, COPD and pulmonary fibrosis. In many cases, they conclude, these events can be linked to a disruption in the microbiome of the patient's lungs - a state known as dysbiosis.

"The old explanation for a lot of these exacerbations was that the airways are acutely infected with bacteria," says Dickson. "But a large number of microbiome studies have shown that this just isn't so. Our old definition of 'infection' doesn't explain what's happening at all."

Instead, argue Dickson and Huffnagle, exacerbations happen when the bacterial communities in a patient's airways are disordered, which creates inflammation, which in turn further disorders the bacterial communities. This cycle of dysbiosis and inflammation is common across a number of chronic inflammatory lung diseases.

The U-M team is launching a study that will sample the microbiome of critically ill patients, like those Dickson treats in the intensive care units at the U-M Health System. Many of these patients are at risk of sepsis or acute respiratory failure, or of infections with Clostridium difficile that take root after a patient has received antibiotics to treat infection. Care in the ICU also often includes treatment with epinephrine and norepinephrine - two of the catecholamines that the team showed are associated with collapse of the lung microbiome.

INFORMATION:

The research relies on the resources of the Medical School's Host Microbiome Initiative and the Michigan Institute for Clinical & Health Research, and is funded by National Institutes for Health grants U01HL098961, UL1TR000433, R01HL114447, T32HL00774921 as well as the Lung HIV Microbiome Initiative, HL098961. References: American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care, doi: 10.1164/rccm.201502-0326LE; PLoS Pathogens, DOI: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004923; Annals of the American Thoracic Society, 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201501-029OC; The Lancet, doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61136-3