(Press-News.org) Scientists have long known that large volcanic explosions can affect the weather by spewing particles that block solar energy and cool the air. Some suspect that extended "volcanic winters" from gigantic blowups helped kill off dinosaurs and Neanderthals. In the summer following Indonesia's 1815 Tambora eruption, frost wrecked crops as far off as New England, and the 1991 blowout of the Philippines' Mount Pinatubo lowered average global temperatures by 0.7 degrees F—enough to mask the effects of manmade greenhouse gases for a year or so.

Now, scientists have shown that eruptions also affect rainfall over the Asian monsoon region, where seasonal storms water crops for nearly half of earth's population. Tree-ring researchers at Columbia University's Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory showed that big eruptions tend to dry up much of central Asia, but bring more rain to southeast Asian countries including Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, Thailand and Myanmar—the opposite of what many climate models predict. Their paper appears in an advance online version of the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

The growth rings of some tree species can be correlated with rainfall, and the observatory's Tree Ring Lab used rings from some 300 sites across Asia to measure the effects of 54 eruptions going back about 800 years. The data came from Lamont's new 1,000-year tree-ring atlas of Asian weather, which has already produced evidence of long, devastating droughts; the researchers also have done a prior study of volcanic cooling in the tropics. "We might think of the study of the solid earth and the atmosphere as two different things, but really everything in the system is interconnected," said Kevin Anchukaitis, the study's lead author. "Volcanoes can be important players in climate over time."

Large explosive eruptions send up sulfur compounds that turn into tiny sulfate particles high into the atmosphere, where they deflect solar radiation. Resulting cooling on earth's surface can last for months or years. (Not all eruptions will do it; for instance, the continuing eruption of Indonesia's Merapi this fall has killed dozens, but this latest episode is probably not big enough by itself to effect large-scale weather changes.) As for rainfall, in the simplest models, lowered temperatures decrease evaporation of water from the surface into the air; and less water vapor translates to less rain. But matters are greatly complicated by atmospheric circulation patterns, cyclic changes in temperatures over the oceans, and the shapes of land masses. Up to now, most climate models incorporating known forces such as changes in the sun and atmosphere have predicted that volcanic explosions would disrupt the monsoon by bringing less rain to southeast Asia--but the researchers found the opposite.

The researchers studied eruptions including one in 1258 from an unknown tropical site, thought to be the largest of the last millennium; the 1600-1601 eruption of Peru's Huaynaputina; Tambora in 1815; the 1883 explosion of Indonesia's Krakatau; Mexico's El Chichón, in 1982; and Pinatubo. The tree rings showed that huge swaths of southern China, Mongolia and surrounding areas consistently dried up in the year or two following big events, while mainland southeast Asia got increased rain. The researchers say there are many possible factors involved, and it would speculative at this point to say exactly why it works this way.

"The data only recently became available to test the models," said Rosanne D'Arrigo, one of the study's coauthors. "Now, it's obvious there's a lot of work to be done to understand how all these different forces interact." For instance, in some episodes pinpointed by the study, it appears that strong cycles of the El Niño-Southern Oscillation, which drives temperatures over the Pacific and Indian oceans and is thought to strongly affect the Asian monsoon, might have counteracted eruptions, lessening their drying or moistening effects. But it could work the other way, too, said Anchukaitis; if atmospheric dynamics and volcanic eruptions come together with the right timing, they could reinforce one another, with drastic results. "Then you get flooding or drought, and neither flooding nor drought is good for the people living in those regions," he said. The study also raises questions whether proposed "geoengineering" schemes to counteract manmade climate change with huge artificial releases of volcanism-like particles might have complex unintended consequences.

Ultimately, said Anchukaitis, such studies should help scientists refine models of how natural and manmade forces might act together to in the future to shift weather patterns—a vital question for all areas of the world.

INFORMATION:

'The Influence of Volcanic Eruptions on the Climate of the Asian Monsoon Region' is at: http://www.agu.org/journals/pip/gl/2010GL044843-pip.pdf

View a slide show: Tree Rings, Climate Change and the Rainy Season

http://www.ldeo.columbia.edu/video/the-tree-ring-project

Author contacts:

Kevin Anchukaitis kja@ldeo.columbia.edu 845-365-8783

Rosanne D'Arrigo rdd@ldeo.columbia.edu 845-365-8617

Brendan Buckley bmb@ldeo.columbia.edu 845-365-8782

Edward Cook drdendro@ldeo.columbia.edu 845-365-8618

More information: Kevin Krajick, Senior Science Writer, The Earth Institute

kkrajick@ei.columbia.edu 212-854-9729

The Earth Institute, Columbia University mobilizes the sciences, education and public policy to achieve a sustainable earth. Through interdisciplinary research among more than 500 scientists in diverse fields, the Institute is adding to the knowledge necessary for addressing the challenges of the 21st century and beyond. With over two dozen associated degree curricula and a vibrant fellowship program, the Earth Institute is educating new leaders to become professionals and scholars in the growing field of sustainable development. We work alongside governments, businesses, nonprofit organizations and individuals to devise innovative strategies to protect the future of our planet. www.earth.columbia.edu

Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, a member of The Earth Institute, is one of the world's leading research centers seeking fundamental knowledge about the origin, evolution and future of the natural world. More than 300 research scientists study the planet from its deepest interior to the outer reaches of its atmosphere, on every continent and in every ocean. From global climate change to earthquakes, volcanoes, nonrenewable resources, environmental hazards and beyond, Observatory scientists provide a rational basis for the difficult choices facing humankind in the planet's stewardship. www.ldeo.columbia.edu

Volcanoes have shifted Asian rainfall

Defying models, some regions drier, others wetter

2010-11-04

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Headgear, mouth guards have little or no impact on reducing concussions in rugby players

2010-11-04

TORONTO, Ont., Nov. 3, 2010 – Existing headgear and mouth guards have limited or no benefit in reducing concussions in rugby players, according to Dr. Michael Cusimano, a neurosurgeon at St. Michael's Hospital.

However, educational injury prevention programs that promote proper playing techniques and enforcement of the rules do result in a significant reduction in concussions and head, neck and spinal injuries, Cusimano concluded after a review of existing studies on the topic.

Cusimano still recommends rugby players wear mouth guards and protective headgear ...

Chromosome imbalances lead to predictable plant defects

2010-11-04

WEST LAFAYETTE, Ind. - Physical defects in plants can be predicted based on chromosome imbalances, a finding that may shed light on how the addition or deletion of genes and the organization of the genome affects organisms, according to a study involving a Purdue University researcher.

The findings identify easily measured characteristics that vary with imbalances of specific chromosomes, said Brian Dilkes, a Purdue assistant professor of horticulture. Understanding why and how those imbalances result in certain characteristics could open the door to correcting those ...

E. coli thrives near plant roots, can contaminate young produce crops

2010-11-04

WEST LAFAYETTE, Ind. - E. coli can live for weeks around the roots of produce plants and transfer to the edible portions, but the threat can be minimized if growers don't harvest too soon, a Purdue University study shows.

Purdue scientists added E. coli to soil through manure application and water treated with manure and showed that the bacteria can survive and are active in the rhizosphere, or the area around the plant roots, of lettuce and radishes. E. coli eventually gets onto the aboveground surfaces of the plants, where it can live for several weeks. Activity in ...

U of M researcher finds public support for HPV vaccine wanes when linked to controversy

2010-11-04

MINNEAPOLIS / ST. PAUL, Minn. (Nov. 2, 2010) – The vaccine that protects against the potentially cancer-causing human papillomavirus (HPV) enjoys wide support in the medical and public health communities. Yet state laws to require young girls to be vaccinated as a requirement for middle school attendance have aroused controversy with parents, politicians, and even medical and public health experts disagreeing about whether such laws are appropriate. News coverage about HPV vaccine requirements tends to amplify this controversy, possibly leading to negative attitudes among ...

Organic onions, carrots and potatoes do not have higher levels of healthful antioxidants

2010-11-04

With the demand for organically produced food increasing, scientists are reporting new evidence that organically grown onions, carrots, and potatoes generally do not have higher levels of healthful antioxidants and related substances than vegetables grown with traditional fertilizers and pesticides. Their study appears in ACS' bi-weekly Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry.

In the study, Pia Knuthsen and colleagues point out that there are many reasons to pay a premium for organic food products. The most important reasons for the popularity of organic food products ...

Built-in timer for improving accuracy of cost saving paper-strip medical tests

2010-11-04

Scientists are reporting the development of a simple, built-in timer intended to improve the accuracy of paper tests and test strips for diagnosing diseases inexpensively at-home and elsewhere. Their study appears in ACS' semi-monthly journal Analytical Chemistry.

Scott Phillips and Hyeran Noh note that so-called point-of-care tests include paper strip tests and others performed at home or bedside instead of in laboratories. They show special promise for improving medical care in developing countries and reducing health care costs elsewhere. When fully developed, these ...

Does adolescent stress lead to mood disorders in adulthood?

2010-11-04

Montreal, November 3, 2010 – Stress may be more hazardous to our mental health than previously believed, according to new research from Concordia University. A series of studies from the institution have found there may be a link between the recent rise in depression rates and the increase of daily stress.

"Major depression has become one of the most pressing health issues in both developing and developed countries," says principal researcher Mark Ellenbogen, a professor at the Concordia Centre for Research in Human Development and a Canada Research Chair in Developmental ...

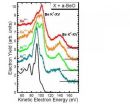

Electrons get confused

2010-11-04

Scientists from Helmholtz-Zentrum Berlin (HZB) observed exotic behaviour from beryllium oxide (BeO) when they bombarded it with high-speed heavy ions: After being shot in this way, the electrons in the BeO appeared "confused", and seemed to completely forget the material properties of their environment. The researchers' measurements show changes in the electronic structure that can be explained by extremely rapid melting around the firing line of the heavy ions. If this interpretation is correct, then this would have to be the fastest melting ever observed. The researchers ...

Levels of coumarin in cassia cinnamon vary greatly even in bark from the same tree

2010-11-04

A "huge" variation exists in the amounts of coumarin in bark samples of cassia cinnamon from trees growing in Indonesia, scientists are reporting in a new study. That natural ingredient in the spice may carry a theoretical risk of causing liver damage in a small number of sensitive people who consume large amounts of cinnamon. The report appears in ACS' bi-weekly Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry.

Friederike Woehrlin and colleagues note that cinnamon is the second most popular spice, next to black pepper, in the United States and Europe. Cinnamon, which comes ...

Small materials poised for big impact in construction

2010-11-04

Bricks, blocks, and steel I-beams — step aside. A new genre of construction materials, made from stuff barely 1/50,000th the width of a human hair, is about to debut in the building of homes, offices, bridges, and other structures. And a new report is highlighting both the potential benefits of these nanomaterials in improving construction materials and the need for guidelines to regulate their use and disposal. The report appears in the monthly journal ACS Nano.

Pedro Alvarez and colleagues note that nanomaterials likely will have a greater impact on the construction ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Alkali cation effects in electrochemical carbon dioxide reduction

Test platforms for charging wireless cars now fit on a bench

$3 million NIH grant funds national study of Medicare Advantage’s benefit expansion into social supports

Amplified Sciences achieves CAP accreditation for cutting-edge diagnostic lab

Fred Hutch announces 12 recipients of the annual Harold M. Weintraub Graduate Student Award

Native forest litter helps rebuild soil life in post-mining landscapes

Mountain soils in arid regions may emit more greenhouse gas as climate shifts, new study finds

Pairing biochar with other soil amendments could unlock stronger gains in soil health

Why do we get a skip in our step when we’re happy? Thank dopamine

UC Irvine scientists uncover cellular mechanism behind muscle repair

Platform to map living brain noninvasively takes next big step

Stress-testing the Cascadia Subduction Zone reveals variability that could impact how earthquakes spread

We may be underestimating the true carbon cost of northern wildfires

Blood test predicts which bladder cancer patients may safely skip surgery

Kennesaw State's Vijay Anand honored as National Academy of Inventors Senior Member

Recovery from whaling reveals the role of age in Humpback reproduction

Can the canny tick help prevent disease like MS and cancer?

Newcomer children show lower rates of emergency department use for non‑urgent conditions, study finds

Cognitive and neuropsychiatric function in former American football players

From trash to climate tech: rubber gloves find new life as carbon capturers materials

A step towards needed treatments for hantaviruses in new molecular map

Boys are more motivated, while girls are more compassionate?

Study identifies opposing roles for IL6 and IL6R in long-term mortality

AI accurately spots medical disorder from privacy-conscious hand images

Transient Pauli blocking for broadband ultrafast optical switching

Political polarization can spur CO2 emissions, stymie climate action

Researchers develop new strategy for improving inverted perovskite solar cells

Yes! The role of YAP and CTGF as potential therapeutic targets for preventing severe liver disease

Pancreatic cancer may begin hiding from the immune system earlier than we thought

Robotic wing inspired by nature delivers leap in underwater stability

[Press-News.org] Volcanoes have shifted Asian rainfallDefying models, some regions drier, others wetter