(Press-News.org) It is hard to believe that they belong to the same species: The large, long-lived queen bee is busy producing offspring throughout her lifetime. The much smaller worker bees, on the other hand, gather food, take care of the beehive, look after and feed the brood – but they are infertile.

"The honey bee is an extreme example of different larval development," Professor Frank Lyko explains. Lyko, a scientist at DKFZ, studies how genes are regulated by chemical labeling with methyl groups. This type of regulation is part of what are called epigenetic regulation mechanisms – chemical alterations in the genetic material which do not change the sequence of DNA building blocks. This regulation mechanism enables the cell to adapt to changing environmental conditions.

Why is a cancer researchers interested in bees? "Cancer cells and healthy cells have identical genomes, but they behave very differently. To a large extent this is due to differences in the methylation of genes. Queen bees and worker bees also share the same genome, despite all differences in appearance. Here, too, methyl labels could be responsible for different larval development," says Lyko.

In a beehive, it is the food alone which determines the future of the offspring: If the larvae are fed pollen, they develop into worker bees. If they are to grow into queen bees, their only food is royal jelly, which is rich in fat and protein. Australian researchers have recently imitated the effects of this power food by turning off the enzyme that labels DNA with methyl groups in bee larvae. These larvae all turned into queens – completely without any royal jelly.

This was a clear indication that it is methyl labels that determine the larvae's fate by influencing the activity of particular genes. In their current work, Lyko and his team have investigated which genes turn a bee into a queen. While previous epigenetic investigations concentrated on the methyl labeling of individual genes, the Heidelberg researchers, jointly with bee experts from Australia, have been the first to compare methylation of the whole genomes of queens and workers. "The bee with its small genome has served as a model for us to test the method. By now, we are able to perform such investigations also in the human genome," Frank Lyko explains.

Other than the richly methylated human genome, the bee genome carries considerably less methyl labels. In more than 550 genes the investigators found clear differences between worker bees and queen bees. These genes have often remained largely unchanged in the course of evolution, which is an indication for researchers that they fulfill important tasks of the cell.

Moreover, Lyko's team identified a previously unknown mechanism by which gene methylation might influence character production. In bees, methyl labels are frequently found at so-called splice sites of genes where the blueprint for protein production is cut. If these recognition sites are made unrecognizable by chemical labels, the cell may possibly produce an altered protein with a different function. "So far, the theory has been that methyl labels block gene activity at the gene switches and thus produce diverging characteristics," Frank Lyko says. "But now we have found evidence to suggest that the mechanism discovered in bees may also play a role in cancer cells." This would mean that epigenetic factors in cancer not only turn genes on or off, but may also be responsible for production of proteins of a completely different kind.

INFORMATION:

Frank Lyko, Sylvain Foret, Robert Kucharski, Stephan Wolf, Cassandra Falckenhayn and Ryszard Maleszka: The Honey Bee Epigenomes: Differential Methylation of Brain DNA in Queens and Workers. PLoS Biology 2010, DOI: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000506

A picture for this press release is available at:

http://www.dkfz.de/de/presse/pressemitteilungen/2010/images/Lyko_Biene.jpg

Picture Source: Tobias Schwerdt, Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum

The German Cancer Research Center (Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum, DKFZ) is the largest biomedical research institute in Germany and is a member of the Helmholtz Association of National Research Centers. More than 2,200 staff members, including 1,000 scientists, are investigating the mechanisms of cancer and are working to identify cancer risk factors. They provide the foundations for developing novel approaches in the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of cancer. In addition, the staff of the Cancer Information Service (KID) offers information about the widespread disease of cancer for patients, their families, and the general public. The Center is funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (90%) and the State of Baden-Württemberg (10%).

Honey bees: Genetic labeling decides about blue blood

2010-11-04

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

A sweet discovery raises hope for treating Ebola, Lassa, Marburg and other fast-acting viruses

2010-11-04

When a team of European researchers sought to discover how a class of antiviral drugs worked, they looked in an unlikely place: the sugar dish. A new research report appearing in the Journal of Leukocyte Biology (http://www.jleukbio.org) suggests that a purified and modified form of a simple sugar chain may stop fast-acting and deadly viruses, such as Ebola, Lassa, or Marburg viruses, in their tracks. This compound, called chlorite-oxidized oxyamylose or COAM, could be a very attractive therapeutic option because not only did this compound enhance the early-stage immune ...

Language appears to shape our implicit preferences

2010-11-04

CAMBRIDGE, Mass., Nov. 3, 2010 -- The language we speak may influence not only our thoughts, but our implicit preferences as well. That's the finding of a study by psychologists at Harvard University, who found that bilingual individuals' opinions of different ethnic groups were affected by the language in which they took a test examining their biases and predilections.

The paper appears in the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology.

"Charlemagne is reputed to have said that to speak another language is to possess another soul," says co-author Oludamini Ogunnaike, ...

Researchers expand cyberspace to fight chronic condition in breast cancer survivors

2010-11-04

COLUMBIA, Mo. – Lymphedema is a chronic condition that causes swelling of the limbs and affects physical, mental and social health. It commonly occurs in breast cancer survivors and is the second-most dreaded effect of treatment, after cancer recurrence. Every day, researchers throughout the world learn more about the condition and how it can be treated. Now, University of Missouri researchers are developing a place in cyberspace where relevant and timely information can be easily stored, searched, and reviewed from anywhere with the goal of improving health care through ...

Earth's climate change 20,000 years ago reversed the circulation of the Atlantic Ocean

2010-11-04

The Atlantic Ocean circulation (termed meridional overturning circulation, MOC) is an important component of the climate system. Warm currents, such as the Gulf Stream, transport energy from the tropics to the subpolar North Atlantic and influence regional weather and climate patterns. Once they arrive in the North the currents cool, their waters sink and with them they transfer carbon from the atmosphere to the abyss. These processes are important for climate but the way the Atlantic MOC responds to climate change is not well known yet.

An international team of investigators ...

Psyllid identification key to area-wide control of citrus greening spread

2010-11-04

At least six psyllid species have been found in the citrus-growing areas of the Rio Grande Valley of Texas, according to a U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) scientist who is working to control the spread of the psyllid-transmitted citrus greening disease.

A few years ago, citrus growers in south Texas noticed a new insect, the Asian citrus psyllid, on their citrus trees. This was a cause for concern, because this tiny pest is responsible for transmitting citrus greening, also known as Huanglongbing (HLB). The disease was first detected in Florida in 2005 and now ...

Main squeeze not needed for boa mom

2010-11-04

In a finding that upends decades of scientific theory on reptile reproduction, researchers at North Carolina State University have discovered that female boa constrictors can squeeze out babies without mating.

More strikingly, the finding shows that the babies produced from this asexual reproduction have attributes previously believed to be impossible.

Large litters of all-female babies produced by the "super mom" boa constrictor show absolutely no male influence – no genetic fingerprint that a male was involved in the reproductive process. All the female babies ...

UGA study finds moving animals not a panacea for habitat loss

2010-11-04

Athens, Ga. – New University of Georgia research suggests moving threatened animals to protected habitats may not always be an effective conservation technique if the breeding patterns of the species are influenced by a social hierarchy.

Research, published in the early online edition of the journal Biological Conservation, found an initial group of gopher tortoises released on St. Catherine's Island, Ga. were three times more likely to produce offspring than a later-introduced group, although the initial group had a much smaller proportion of reproduction-aged males.

"There ...

Most river flows across the US are altered by land and water management

2010-11-04

The amount of water flowing in streams and rivers has been significantly altered in nearly 90 percent of waters that were assessed in a new nationwide USGS study. Flow alterations are a primary contributor to degraded river ecosystems and loss of native species.

"This USGS assessment provides the most geographically extensive analysis to date of stream flow alteration," said Bill Werkheiser, USGS Associate Director for Water. "Findings show the pervasiveness of stream flow alteration resulting from land and water management, the significant impact of altered stream ...

The developmental dynamics of the maize leaf transcriptome

2010-11-04

Photosynthesis is arguably the most impressive feat of nature, where plants harvest light energy and convert it into the building blocks of life at fantastically high efficiency. Indeed modern civilization became possible only with the cultivation of plants for food, shelter and clothing.

While scientists have been able to discover details of the fascinating process by which plants store solar energy as chemical energy, how developing plants build and regulate their solar reactors is still poorly understood. How many genes are involved, and which are the most important? ...

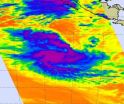

Tropical Storm Anggrek is tightly wrapped in NASA satellite imagery

2010-11-04

Bands of strong thunderstorms are wrapping around the center of Tropical Storm Anggrek in the Southern Indian Ocean, according to satellite imagery. NASA's Aqua satellite captured an infrared look at those strong thunderstorms today.

NASA's Aqua satellite passed over Anggrek on Nov. 3 at 07:05 UTC (3:05 a.m. EDT) and the Atmospheric Infrared Sounder (AIRS) instrument onboard captured an infrared image of the cold thunderstorms within the system. The image showed that strong, high thunderstorm cloud tops tightly circled the storm's center. There was also strong convection ...