(Press-News.org) CINCINNATI – Analyzing the genomes of twin 3-year-old sisters – one healthy and one with aggressive leukemia – led an international team of researchers to identify a novel molecular target that could become a way to treat recurring and deadly malignancies.

Scientists in China and the United States report their findings online Feb. 9 in Nature Genetics. The study points to a molecular pathway involving a gene called SETD2, which can mutate in blood cells during a critical step as DNA is being transcribed and replicated.

The findings stem from the uniquely rare opportunity to compare the whole genomes of the monozygotic twin sisters (which means they came from a single egg). This led to a series of follow up experiments in human samples from leukemia patients and mouse models of human disease. Those tests verified and extended initial findings researchers gleaned from the twin sisters' blood samples, according to Gang Huang, PhD, co-corresponding author and a researcher in the divisions of Pathology and Experimental Hematology and Cancer Biology at Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center.

"We reasoned that monozygotic twins discordant for human leukemia would have identical inherited genetic backgrounds and well-matched tissue-specific events," Huang said. "This provided a strong basis for comparison and analysis. We identified a gene mutation involving SETD2 that contributes to the initiation and progression of leukemia by promoting the self-renewal potential of leukemia stem cells."

The twin sisters' genomes were compared at the laboratory of co-corresponding author Qian-fei Wang, PhD, Beijing Institute of Genomics, Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing, China. The sick sister had a particularly acute and aggressive form of the acute myeloid leukemia (AML) known as MLL, or multi-lineage leukemia.

Acute and aggressive leukemia like MLL develops and progresses rapidly in patients, requiring prompt treatment with chemotherapy, radiation or bone marrow transplant. These treatments can be risky or only partially effective. About 70 percent of people with AML respond initially to standard chemotherapy. Unfortunately, five-year survival rates vary between 15-70 percent, depending on the subtype of AML.

The researchers – including co-corresponding author Tao Cheng, MD, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences & Peking Union Medical College in Tianjin, China – are searching for improved and more targeted treatment strategies. The authors show in their current study that the onset of aggressive and acute leukemia is fueled by a spiraling cascade of multiple gene mutations and what are called chromosomal translocations – essentially incorrect alignments of DNA and genetic information during cell replication.

In comparing the blood cells of both twin sisters, these researchers identified a chromosomal translocation generated what is known as the MLL-NRIP3 fusion leukemia gene. When they activated the MLL-NRIP3 gene in laboratory mouse models, the animals developed the same type of leukemia, but it took a long period of time for them to do so. Researchers said this suggested that there had to be additional cooperative epigenetic and molecular events in play to induce full-blown leukemia.

The authors went on to demonstrate that activation of the MLL-NRIP3 fusion leukemia gene cooperated with the molecular cascade (including mutations in SETD2) to cause the multi-lineage form of acute myeloid leukemia (AML). The scientists' initial clue came by looking for additional genomic alterations in the leukemic blood cells of the sick twin sister. They discovered activation of the MLL-NRIP3 fusion leukemia started the molecular cascade that led to bi-allelic (two mutations) in the gene SETD2 – a tumor suppressor and enzyme that regulates a specific histone modification protein called H3K36me3.

During a process called transcriptional elongation, SETD2 and H3K36me3 normally mark the zone for accurate gene transcription along the DNA. In the case of the sick twin sister, the gene mutations and molecular cascade disrupted the H3K36me3 mark, leading to abnormal transcription and the multi-lineage form of acute leukemia.

Researchers then analyzed blood samples from 241 people who had different forms acute leukemia. SETD2 mutations were found in samples from 6.2 percent of those patients. Patients with SETD2 mutations also had a leukemia associated with major chromosomal translocations and disruption of the H3K36me3 mark.

In follow up tests on cell cultures of pre-leukemic cells and mouse models, researchers saw the same progression of gene mutations and related molecular events fuel the growth of leukemic cells. Researchers also noticed mutation of SETD2 activated two genes (MTOR and JAK-STAT) that known contributors to cancer and leukemia. The scientists decided to test two existing targeted molecular inhibitors of MTOR on pre-leukemic cells that are generated by SETD2 gene mutations.

That treatment resulted in a marked decrease in cell growth, indicating that SETD2 mutations activate numerous molecular pathways to generate leukemia. Huang said the tests also demonstrate that there are multiple opportunities to find new molecular targets for developing more effective drugs – in particular those that would target the MLL fusion-SETD2-H3K36me3 pathway for treating acute and aggressive multi-lineage leukemia.

Researchers are following up their current study by identifying additional pathways activated by mutations of SETD2. They also are looking possible new molecular targets and therapeutic strategies for block disruptions in the MLL fusions-SETD2-H3K36me3 pathway.

INFORMATION:

Other collaborating institutions include: the Institute of Hematology and Blood Diseases Hospital at the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College; the University of Science & Technology, Wuhan, Hubei, China; Changhai Hospital, Second Military Medical University, Shanghai, China; the University Feinberg School of Medicine and Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children's Hospital of Chicago Research Center, Chicago. Co-first authors are: Xiaofan Zhu, Fuhong He, Huimin Zeng, Shaoping Ling and Aili Chen.

Funding support came from: the China Ministry of Science and Technology (2011CB964801, 2012CB966600, 2010DFB30270); the Chinese Academy of Sciences; the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81090411, 81000220, 81130074, 30825017) Tianjin Municipal Science & Technology Commission (09ZCZDSF03800).

About Cincinnati Children's:

Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center ranks third in the nation among all Honor Roll hospitals in U.S. News and World Report's 2013 Best Children's Hospitals ranking. It is ranked #1 for cancer and in the top 10 for nine of 10 pediatric specialties. Cincinnati Children's, a non-profit organization, is one of the top three recipients of pediatric research grants from the National Institutes of Health, and a research and teaching affiliate of the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine. The medical center is internationally recognized for improving child health and transforming delivery of care through fully integrated, globally recognized research, education and innovation. Additional information can be found at http://www.cincinnatichildrens.org. Connect on the Cincinnati Children's blog, via Facebook and on Twitter.

Study involving twin sisters provides clues for battling aggressive cancers

2014-02-10

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Genome editing goes hi-fi

2014-02-10

SAN FRANCISCO, CA—February 9, 2014—Sometimes biology is cruel. Sometimes simply a one-letter change in the human genetic code is the difference between health and a deadly disease. But even though doctors and scientists have long studied disorders caused by these tiny changes, replicating them to study in human stem cells has proven challenging. But now, scientists at the Gladstone Institutes have found a way to efficiently edit the human genome one letter at a time—not only boosting researchers' ability to model human disease, but also paving the way for therapies that ...

Cochlear implants -- with no exterior hardware

2014-02-10

Cochlear implants — medical devices that electrically stimulate the auditory nerve — have granted at least limited hearing to hundreds of thousands of people worldwide who otherwise would be totally deaf. Existing versions of the device, however, require that a disk-shaped transmitter about an inch in diameter be affixed to the skull, with a wire snaking down to a joint microphone and power source that looks like an oversized hearing aid around the patient's ear.

Researchers at MIT's Microsystems Technology Laboratory (MTL), together with physicians from Harvard Medical ...

Scientists invent advanced approach to identify new drug candidates from genome sequence

2014-02-10

JUPITER, FL—February 9, 2014—In research that could ultimately lead to many new medicines, scientists from the Florida campus of The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) have developed a potentially general approach to design drugs from genome sequence. As a proof of principle, they identified a highly potent compound that causes cancer cells to attack themselves and die.

"This is the first time therapeutic small molecules have been rationally designed from only an RNA sequence—something many doubted could be done," said Matthew Disney, PhD, an associate professor at TSRI ...

Fight or flight? Vocal cues help deer decide during mating season

2014-02-10

Previous studies have shown that male fallow deer, known as bucks, can call for a mate more than 3000 times per hour during the rut (peak of the mating season), and their efforts in calling, fighting and mating can leave them sounding hoarse.

In this new study, published today (10 February) in the journal Behavioral Ecology, scientists were able to gauge that fallow bucks listen to the sound quality of rival males' calls and evaluate how exhausted the caller is and whether they should fight or keep their distance.

"Fallow bucks are among the most impressive vocal athletes ...

Pacific trade winds stall global surface warming -- for now

2014-02-10

Heat stored in the western Pacific Ocean caused by an unprecedented strengthening of the equatorial trade winds appears to be largely responsible for the hiatus in surface warming observed over the past 13 years.

New research published today in the journal Nature Climate Change indicates that the dramatic acceleration in winds has invigorated the circulation of the Pacific Ocean, causing more heat to be taken out of the atmosphere and transferred into the subsurface ocean, while bringing cooler waters to the surface.

"Scientists have long suspected that extra ocean ...

Seven new genetic regions linked to type 2 diabetes

2014-02-10

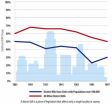

Seven new genetic regions associated with type 2 diabetes have been identified in the largest study to date of the genetic basis of the disease.

DNA data was brought together from more than 48,000 patients and 139,000 healthy controls from four different ethnic groups. The research was conducted by an international consortium of investigators from 20 countries on four continents, co-led by investigators from Oxford University's Wellcome Trust Centre for Human Genetics.

The majority of such 'genome-wide association studies' have been done in populations with European ...

Optogenetic toolkit goes multicolor

2014-02-10

CAMBRIDGE, MA -- Optogenetics is a technique that allows scientists to control neurons' electrical activity with light by engineering them to express light-sensitive proteins. Within the past decade, it has become a very powerful tool for discovering the functions of different types of cells in the brain.

Most of these light-sensitive proteins, known as opsins, respond to light in the blue-green range. Now, a team led by MIT has discovered an opsin that is sensitive to red light, which allows researchers to independently control the activity of two populations of neurons ...

Clues to cancer pathogenesis found in cell-conditioned media

2014-02-10

Philadelphia, PA, February 10, 2014 – Primary effusion lymphoma (PEL) is a rare B-cell neoplasm distinguished by its tendency to spread along the thin serous membranes that line body cavities without infiltrating or destroying nearby tissue. By growing PEL cells in culture and analyzing the secretome (proteins secreted into cell-conditioned media), investigators have identified proteins that may explain PEL pathogenesis, its peculiar cell adhesion, and migration patterns. They also recognized related oncogenic pathways, thereby providing rationales for more individualized ...

Smoking linked with increased risk of most common type of breast cancer

2014-02-10

Young women who smoke and have been smoking a pack a day for a decade or more have a significantly increased risk of developing the most common type of breast cancer. That is the finding of an analysis published early online in Cancer, a peer-reviewed journal of the American Cancer Society. The study indicates that an increased risk of breast cancer may be another health risk incurred by young women who smoke.

The majority of recent studies evaluating the relationship between smoking and breast cancer risk among young women have found that smoking is linked with an increased ...

No strength in numbers

2014-02-10

Urban legislators have long lamented that they do not get their fair share of bills passed in state governments, often blaming rural and suburban interests for blocking their efforts. Now a new study confirms one of those suspicions but surprisingly refutes the other.

The analysis—of 1,736 bills in 13 states over 120 years—found that big-city legislation was passed at dramatically lower rates than bills for smaller places.

However, rural and suburban colleagues should not be blamed for the dismal track record, conclude co-authors Gerald Gamm of the University of Rochester ...