(Press-News.org) VIDEO:

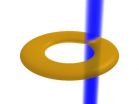

This is an animation showing a laser beam stirring a ring shaped quantum gas.

Click here for more information.

Atomtronics is an emerging technology whereby physicists use ensembles of atoms to build analogs to electronic circuit elements. Modern electronics relies on utilizing the charge properties of the electron. Using lasers and magnetic fields, atomic systems can be engineered to have behavior analogous to that of electrons, making them an exciting platform for studying and generating alternatives to charge-based electronics.

Using a superfluid atomtronic circuit, JQI physicists, led by Gretchen Campbell, have demonstrated a tool that is critical to electronics: hysteresis. This is the first time that hysteresis has been observed in an ultracold atomic gas. This research is published in the February 13 issue of Nature magazine, whose cover features an artistic impression of the atomtronic system.

Lead author Stephen Eckel explains, "Hysteresis is ubiquitous in electronics. For example, this effect is used in writing information to hard drives as well as other memory devices. It's also used in certain types of sensors and in noise filters such as the Schmitt trigger." Here is an example demonstrating how this common trigger is employed to provide hysteresis. Consider an air-conditioning thermostat, which contains a switch to regulate a fan. The user sets a desired temperature. When the room air exceeds this temperature, a fan switches on to cool the room. When does the fan know to turn off? The fan actually brings the temperature lower to a different set-point before turning off. This mismatch between the turn-on and turn-off temperature set-points is an example of hysteresis and prevents fast switching of the fan, which would be highly inefficient.

In the above example, the hysteresis is programmed into the electronic circuit. In this research, physicists observed hysteresis that is an inherent natural property of a quantum fluid. 400,000 sodium atoms are cooled to condensation, forming a type of quantum matter called a Bose-Einstein condensate (BEC), which has a temperature around 0.000000100 Kelvin (0 Kelvin is absolute zero). The atoms reside in a doughnut-shaped trap that is only marginally bigger than a human red blood cell. A focused laser beam intersects the ring trap and is used to stir the quantum fluid around the ring.

While BECs are made from a dilute gas of atoms less dense than air, they have unusual collective properties, making them more like a fluid—or in this case, a superfluid. What does this mean? First discovered in liquid helium in 1937, this form of matter, under some conditions, can flow persistently, undeterred by friction. A consequence of this behavior is that the fluid flow or rotational velocity around the team's ring trap is quantized, meaning it can only spin at certain specific speeds. This is unlike a non-quantum (classical) system, where its rotation can vary continuously and the viscosity of the fluid plays a substantial role.

Because of the characteristic lack of viscosity in a superfluid, stirring this system induces drastically different behavior. Here, physicists stir the quantum fluid, yet the fluid does not speed up continuously. At a critical stir-rate the fluid jumps from having no rotation to rotating at a fixed velocity. The stable velocities are a multiple of a quantity that is determined by the trap size and the atomic mass.

This same laboratory has previously demonstrated persistent currents and this quantized velocity behavior in superfluid atomic gases. Now they have explored what happens when they try to stop the rotation, or reverse the system back to its initial velocity state. Without hysteresis, they could achieve this by reducing the stir-rate back below the critical value causing the rotation to cease. In fact, they observe that they have to go far below the critical stir-rate, and in some cases reverse the direction of stirring to see the fluid return to the lower quantum velocity state.

Controlling this hysteresis opens up new possibilities for building a practical atomtronic device. For instance, there are specialized superconducting electronic circuits that are precisely controlled by magnetic fields and in turn, small magnetic fields affect the behavior of the circuit itself. Thus, these devices, called SQuIDs (superconducting quantum interference devices), are used as magnetic field sensors. "Our current circuit is analogous to a specific kind of SQuID called an RF-SQuID", says Campbell. "In our atomtronic version of the SQuID, the focused laser beam induces rotation when the speed of the laser beam "spoon" hits a critical value. We can control where that transition occurs by varying the properties of the "spoon". Thus, the atomtronic circuit could be used as an inertial sensor."

This two-velocity state quantum system has the ingredients for making a qubit. However, this idea has some significant obstacles to overcome before it could be a viable choice. Atomtronics is a young technology and physicists are still trying to understand these systems and their potential. One current focus for Campbell's team includes exploring the properties and capabilities of the novel device by adding complexities such as a second ring.

INFORMATION:

This research was supported by the NSF Physics Frontier Center at JQI.

Stirring-up atomtronics in a quantum circuit

What's so 'super' about this superfluid

2014-02-13

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Ancient settlements and modern cities follow same rules of development, says CU-Boulder

2014-02-13

Recently derived equations that describe development patterns in modern urban areas appear to work equally well to describe ancient cities settled thousands of years ago, according to a new study led by a researcher at the University of Colorado Boulder.

"This study suggests that there is a level at which every human society is actually very similar," said Scott Ortman, assistant professor of anthropology at CU-Boulder and lead author of the study published in the journal PLOS ONE. "This awareness helps break down the barriers between the past and present and allows us ...

America's only Clovis skeleton had its genome mapped

2014-02-13

They lived in America about 13,000 years ago where they hunted mammoth, mastodons and giant bison with big spears. The Clovis people were not the first humans in America, but they represent the first humans with a wide expansion on the North American continent – until the culture mysteriously disappeared only a few hundred years after its origin. Who the Clovis people were and which present day humans they are related to has been discussed intensely and the issue has a key role in the discussion about how the Americas were peopled. Today there exists only one human skeleton ...

New target for psoriasis treatment discovered

2014-02-13

Researchers at King's College London have identified a new gene (PIM1), which could be an effective target for innovative treatments and therapies for the human autoimmune disease, psoriasis.

Psoriasis affects around 2 per cent of people in the UK and causes dry, red lesions on the skin which can become sore or itchy and can have significant impact on the sufferer's quality of life.

It is thought that psoriasis is caused by a problem with the body's immune system in which new skin cells are created too rapidly, causing a build up of flaky patches on the skin's surface. ...

Two parents with Alzheimer's disease? Disease may show up decades early on brain scans

2014-02-13

MINNEAPOLIS – People who are dementia-free but have two parents with Alzheimer's disease may show signs of the disease on brain scans decades before symptoms appear, according to a new study published in the February 12, 2014, online issue of Neurology®, the medical journal of the American Academy of Neurology.

"Studies show that by the time people come in for a diagnosis, there may be a large amount of irreversible brain damage already present," said study author Lisa Mosconi, PhD, with the New York University School of Medicine in New York. "This is why it is ideal ...

Solving an evolutionary puzzle

2014-02-13

For four decades, waste from nearby manufacturing plants flowed into the waters of New Bedford Harbor—an 18,000-acre estuary and busy seaport. The harbor, which is contaminated with polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and heavy metals, is one of the EPA's largest Superfund cleanup sites.

It's also the site of an evolutionary puzzle that researchers at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) and their colleagues have been working to solve.

Atlantic killifish—common estuarine fishes about three inches long—are not only tolerating the toxic conditions in the harbor, they ...

NIF experiments show initial gain in fusion fuel

2014-02-13

LIVERMORE, Calif. – Ignition – the process of releasing fusion energy equal to or greater than the amount of energy used to confine the fuel – has long been considered the "holy grail" of inertial confinement fusion science. A key step along the path to ignition is to have "fuel gains" greater than unity, where the energy generated through fusion reactions exceeds the amount of energy deposited into the fusion fuel.

Though ignition remains the ultimate goal, the milestone of achieving fuel gains greater than 1 has been reached for the first time ever on any facility. ...

Well-child visits linked to more than 700,000 subsequent flu-like illnesses

2014-02-13

CHICAGO (February 12, 2014) – New research shows that well-child doctor appointments for annual exams and vaccinations are associated with an increased risk of flu-like illnesses in children and family members within two weeks of the visit. This risk translates to more than 700,000 potentially avoidable illnesses each year, costing more than $490 million annually. The study was published in the March issue of Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology, the journal of the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America.

"Well child visits are critically important. However, ...

'Viewpoint' addresses IOM report on genome-based therapeutics and companion diagnostics

2014-02-13

The promise of personalized medicine, says University of Vermont (UVM) molecular pathologist Debra Leonard, M.D., Ph.D., is the ability to tailor therapy based on markers in the patient's genome and, in the case of cancer, in the cancer's genome. Making this determination depends on not one, but several genetic tests, but the system guiding the development of those tests is complex, and plagued with challenges.

In a February 12, 2014 Online First Journal of the American Medical Association "Viewpoint" article, Leonard and colleagues address this issue in conjunction ...

Rare bacteria outbreak in cancer clinic tied to lapse in infection control procedure

2014-02-13

CHICAGO (February 12, 2014) – Improper handling of intravenous saline at a West Virginia outpatient oncology clinic was linked with the first reported outbreak of Tsukamurella spp., gram-positive bacteria that rarely cause disease in humans, in a new report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The report was published in the March issue of Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology, the journal of the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America.

"This outbreak illustrates the need for outpatient clinics to follow proper infection control guidelines ...

No such thing as porn 'addiction,' researchers say

2014-02-13

Journalists and psychologists are quick to describe someone as being a porn "addict," yet there's no strong scientific research that shows such addictions actually exists. Slapping such labels onto the habit of frequently viewing images of a sexual nature only describes it as a form of pathology. These labels ignore the positive benefits it holds. So says David Ley, PhD, a clinical psychologist in practice in Albuquerque, NM, and Executive Director of New Mexico Solutions, a large behavioral health program. Dr. Ley is the author of a review article about the so-called "pornography ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy may help prevent preeclampsia

Menopausal hormone therapy not linked to increased risk of death

Chronic shortage of family doctors in England, reveals BMJ analysis

Booster jabs reduce the risks of COVID-19 deaths, study finds

Screening increases survival rate for stage IV breast cancer by 60%

ACC announces inaugural fellow for the Thad and Gerry Waites Rural Cardiovascular Research Fellowship

University of Oklahoma researchers develop durable hybrid materials for faster radiation detection

Medicaid disenrollment spikes at age 19, study finds

Turning agricultural waste into advanced materials: Review highlights how torrefaction could power a sustainable carbon future

New study warns emerging pollutants in livestock and aquaculture waste may threaten ecosystems and public health

Integrated rice–aquatic farming systems may hold the key to smarter nitrogen use and lower agricultural emissions

Hope for global banana farming in genetic discovery

Mirror image pheromones help beetles swipe right

Prenatal lead exposure related to worse cognitive function in adults

Research alert: Understanding substance use across the full spectrum of sexual identity

Pekingese, Shih Tzu and Staffordshire Bull Terrier among twelve dog breeds at risk of serious breathing condition

Selected dog breeds with most breathing trouble identified in new study

Interplay of class and gender may influence social judgments differently between cultures

Pollen counts can be predicted by machine learning models using meteorological data with more than 80% accuracy even a week ahead, for both grass and birch tree pollen, which could be key in effective

Rewriting our understanding of early hominin dispersal to Eurasia

Rising simultaneous wildfire risk compromises international firefighting efforts

Honey bee "dance floors" can be accurately located with a new method, mapping where in the hive forager bees perform waggle dances to signal the location of pollen and nectar for their nestmates

Exercise and nutritional drinks can reduce the need for care in dementia

Michelson Medical Research Foundation awards $750,000 to rising immunology leaders

SfN announces Early Career Policy Ambassadors Class of 2026

Spiritual practices strongly associated with reduced risk for hazardous alcohol and drug use

Novel vaccine protects against C. diff disease and recurrence

An “electrical” circadian clock balances growth between shoots and roots

Largest study of rare skin cancer in Mexican patients shows its more complex than previously thought

Colonists dredged away Sydney’s natural oyster reefs. Now science knows how best to restore them.

[Press-News.org] Stirring-up atomtronics in a quantum circuitWhat's so 'super' about this superfluid