(Press-News.org) DENVER (Feb. 13, 2014) – When a tsunami struck American Samoa in 2009, indigenous institutions on the islands provided effective disaster relief that could help federal emergency managers in similar communities nationwide, according to a study from the University of Colorado Denver and the University of Hawaii at Manoa.

The study found that following the tsunami, residents of the remote U.S. territory in the South Pacific relied on Fa'aSamoa or The Samoan Way, an umbrella term incorporating a variety of traditional institutions governing the lives of its citizens.

"We found that communities like this have strong traditions that may not fit into the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) model but they are still highly effective," said study author Andrew Rumbach, PhD, assistant professor of planning and design at CU Denver's College of Architecture and Planning. "We think these same kinds of traditions could play important roles in disaster preparation, response and recover in American Indian communities, Alaskan villages, and among other indigenous people."

The study was published Thursday in the journal Ecology and Society and available at http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/issues/article.php/6189

The 2009 tsunami resulted from three undersea earthquakes that sent a wall of water crashing into American Samoa, killing 34, injuring hundreds more and causing tens of millions of dollars in damage.

Immediately after, the leaders or matai began organizing the young men or aumaga to begin rescuing tsunami victims and clearing debris from roads and critical infrastructure, said Rumbach.

"The aumaga were crucially important for emergency response because with such widespread devastation across the island, they were the de facto first responders," he said. "Based in each village they are capable of responding to events locally and without having to be dispatched from larger population centers."

The association of village women, aualuma, provided first aid, food and water to the victims.

Another traditional institution, the pulenu'u or village mayors, helped mitigate the destruction by sounding alarms in each community to warn of the impending tsunami. That action is credited with saving Amanave, a community of 300 that was able to evacuate before water destroyed virtually the entire village.

All the while, extended families known as aigas offered shelter, food and other aid to vulnerable individuals.

"Supporting indigenous institutions through disaster management policies and programs leverages existing networks with high levels of social capital, while simultaneously strengthening those institutions and making them relevant to contemporary challenges," the study said. "It's a `win-win' scenario."

Rumbach said FEMA's recent turn toward more community-based disaster management efforts offers the chance to create more flexible response plans for diverse conditions, needs and priorities.

"In times of crisis these institutions played role of first responder all without specific training," said Rumbach. "That response could be improved by being trained in CPR, evacuation of the elderly and other skills. But we could incorporate these kinds of traditional responses into FEMA."

The lessons learned from American Samoa could be used in other island territories or traditional communities in the U.S.

"We often come in after disasters and set up whole new systems but in these places we could use institutions already in place," Rumbach said. "Traditional communities have a lot of capacity.

INFORMATION:

The College of Architecture and Planning is among the largest colleges of architecture and related design and planning disciplines in the U.S. Located on the University of Colorado Denver's downtown campus and the University of Colorado-Boulder, CAP brings together faculty, students and practitioners who share common pursuits in communities of interest including: emerging practices in design, sustainable urbanism, the creation of healthy environments and the preservation of cultural heritage. CAP is one of 13 schools and colleges at CU Denver which offers more than 128 degrees.

Study highlights indigenous response to natural disaster

Experience in American Samoa could be replicated elsewhere

2014-02-14

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Berkeley Lab researchers at AAAS 2014

2014-02-14

Can more accurate climate models help us understand extreme weather events? Can we use

synthetic biology to create better biofuels? These questions, and the ongoing search for Dark

Matter and better photovoltaic materials, are just some of the presentations by Lawrence

Berkeley National Lab researchers at this year's AAAS meeting. Here's a quick look at Berkeley

Lab@AAAS:

Friday, Feb. 14

1:00-2:30

Opportunities for New Materials in

Photovoltaics (Toronto Room, Hyatt Regency)

Ramamoorthy Ramesh

The

Department of Energy's ...

Superconductivity in orbit: Scientists find new path to loss-free electricity

2014-02-14

UPTON, NY—Armed with just the right atomic arrangements, superconductors allow electricity to flow without loss and radically enhance energy generation, delivery, and storage. Scientists tweak these superconductor recipes by swapping out elements or manipulating the valence electrons in an atom's outermost orbital shell to strike the perfect conductive balance. Most high-temperature superconductors contain atoms with only one orbital impacting performance—but what about mixing those elements with more complex configurations?

Now, researchers at the U.S. Department of ...

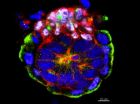

Rewriting the text books: Scientists crack open 'black box' of development

2014-02-14

We know much about how embryos develop, but one key stage – implantation – has remained a

mystery. Now, scientists from Cambridge have discovered a way to study and film this 'black box'

of development. Their results – which will lead to the rewriting of biology text books worldwide

– are published in the journal Cell. Embryo development in mammals occurs in two phases.

During the first phase, pre-implantation, the embryo is a small, free-floating ball of cells

called a blastocyst. In the second, post-implantation, phase the blastocyst embeds itself in the

mother's ...

A role of glucose tolerance could make the adaptor protein p66Shc a new target for cancer and diabetes

2014-02-14

[TORONTO,Canada, Feb 18, 2014] – A protein that has been known until recently as part of a complex communications network within the cell also plays a direct role in regulating sugar metabolism, according to a new study published on-line in the journal Science Signaling (February 18, 2014).

Cell growth and metabolism are tightly controlled processes in our cells. When these functions are disturbed, diseases such as cancer and diabetes occur. Mohamed Soliman, a PhD candidate at the Lunenfeld Tanenbaum Research Institute at Mount Sinai Hospital, found a unique role for ...

IBEX research shows influence of galactic magnetic field extends beyond our solar system

2014-02-14

In a report published today, new research suggests the enigmatic "ribbon" of energetic

particles discovered at the edge of our solar system by NASA's Interstellar Boundary Explorer (IBEX)

may be only a small sign of the vast influence of the galactic magnetic field.

IBEX researchers have sought answers about the ribbon since its discovery in 2009. Comprising

primarily space physicists, the IBEX team realized that the galactic magnetic field wrapped around

our heliosphere — the giant "bubble" that envelops and protects our solar system — appears to

determine the orientation ...

Rebuilding the brain after stroke

2014-02-14

DETROIT – Enhancing the brain's inherent ability to rebuild itself after a stroke with molecular

components of stem cells holds enormous promise for treating the leading cause of long-term

disability in adults.

Michael Chopp, Ph.D., Scientific Director of the Henry Ford Neuroscience Institute, will present

this approach to treating neurological diseases Thursday, Feb. 13, at the American Heart

Association's International Stroke Conference in San Diego.

Although most stroke victims recover some ability to voluntarily use their hands and other body

parts, half are ...

Amidst bitter cold and rising energy costs, new concerns about energy insecurity

2014-02-14

February 13,2014 --With many regions of the country braced by an unrelenting cold snap, the problem of energy insecurity continues to go unreported despite its toll on the most vulnerable. In a new brief, researchers at Columbia University's Mailman School of Public Health paint a picture of the families most impacted by this problem and suggest recommendations to alleviate its chokehold on millions of struggling Americans. The authors note that government programs to address energy insecurity are coming up short, despite rising energy costs.

Energy Insecurity (EI) is ...

Harvard scientists find cell fate switch that decides liver, or pancreas?

2014-02-14

Harvard stem cell scientists have a new theory for how stem cells decide whether to become

liver or pancreatic cells during development. A cell's fate, the researchers found, is determined by

the nearby presence of prostaglandin E2, a messenger molecule best known for its role in

inflammation and pain. The discovery, published in the journal Developmental Cell, could potentially

make liver and pancreas cells easier to generate both in the lab and for future cell therapies.

Wolfram Goessling, MD, PhD, and Trista North, PhD, both principal faculty members of the

Harvard ...

Arctic biodiversity under serious threat from climate change according to new report

2014-02-14

Unique and irreplaceable Arctic wildlife and landscapes are crucially at risk due to global warming caused by human activities according to the Arctic Biodiversity Assessment (ABA), a new report prepared by 253 scientists from 15 countries under the auspices of the Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna (CAFF), the biodiversity working group of the Arctic Council.

"An entire bio-climatic zone, the high Arctic, may disappear. Polar bears and the other highly adapted organisms cannot move further north, so they may go extinct. We risk losing several species forever," says ...

Pregabalin effectively treats restless leg syndrome with less risk of worsening symptoms

2014-02-13

A report in the Feb. 13 New England Journal of Medicine confirms previous studies suggesting that long-term treatment with the type of drugs commonly prescribed to treat restless leg syndrome (RLS) can cause a serious worsening of the condition in some patients. The year-long study from a multi-institutional research team found that pregabalin – which is FDA-approved to treat nerve pain, seizures, and other conditions – was effective in reducing RLS symptoms and was much less likely to cause symptom worsening than pramipexole, one of several drugs that activate the dopamine ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy may help prevent preeclampsia

Menopausal hormone therapy not linked to increased risk of death

Chronic shortage of family doctors in England, reveals BMJ analysis

Booster jabs reduce the risks of COVID-19 deaths, study finds

Screening increases survival rate for stage IV breast cancer by 60%

ACC announces inaugural fellow for the Thad and Gerry Waites Rural Cardiovascular Research Fellowship

University of Oklahoma researchers develop durable hybrid materials for faster radiation detection

Medicaid disenrollment spikes at age 19, study finds

Turning agricultural waste into advanced materials: Review highlights how torrefaction could power a sustainable carbon future

New study warns emerging pollutants in livestock and aquaculture waste may threaten ecosystems and public health

Integrated rice–aquatic farming systems may hold the key to smarter nitrogen use and lower agricultural emissions

Hope for global banana farming in genetic discovery

Mirror image pheromones help beetles swipe right

Prenatal lead exposure related to worse cognitive function in adults

Research alert: Understanding substance use across the full spectrum of sexual identity

Pekingese, Shih Tzu and Staffordshire Bull Terrier among twelve dog breeds at risk of serious breathing condition

Selected dog breeds with most breathing trouble identified in new study

Interplay of class and gender may influence social judgments differently between cultures

Pollen counts can be predicted by machine learning models using meteorological data with more than 80% accuracy even a week ahead, for both grass and birch tree pollen, which could be key in effective

Rewriting our understanding of early hominin dispersal to Eurasia

Rising simultaneous wildfire risk compromises international firefighting efforts

Honey bee "dance floors" can be accurately located with a new method, mapping where in the hive forager bees perform waggle dances to signal the location of pollen and nectar for their nestmates

Exercise and nutritional drinks can reduce the need for care in dementia

Michelson Medical Research Foundation awards $750,000 to rising immunology leaders

SfN announces Early Career Policy Ambassadors Class of 2026

Spiritual practices strongly associated with reduced risk for hazardous alcohol and drug use

Novel vaccine protects against C. diff disease and recurrence

An “electrical” circadian clock balances growth between shoots and roots

Largest study of rare skin cancer in Mexican patients shows its more complex than previously thought

Colonists dredged away Sydney’s natural oyster reefs. Now science knows how best to restore them.

[Press-News.org] Study highlights indigenous response to natural disasterExperience in American Samoa could be replicated elsewhere