(Press-News.org) BOSTON — A new bioprinting method developed at the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University and the Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS) creates intricately patterned 3D tissue constructs with multiple types of cells and tiny blood vessels. The work represents a major step toward a longstanding goal of tissue engineers: creating human tissue constructs realistic enough to test drug safety and effectiveness.

The method also represents an early but important step toward building fully functional replacements for injured or diseased tissue that can be designed from CAT scan data using computer-aided design (CAD), printed in 3D at the push of a button, and used by surgeons to repair or replace damaged tissue.

"This is the foundational step toward creating 3D living tissue," said Jennifer Lewis, Ph.D., senior author of the study, who is a Core Faculty Member of the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University, and the Hansjörg Wyss Professor of Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard SEAS. Along with lead author David Kolesky, a graduate student in SEAS and the Wyss Institute, her team reported the results February 18 in the journal Advanced Materials.

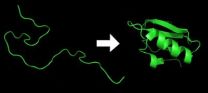

Tissue engineers have tried for years to produce lab-grown vascularized human tissues robust enough to serve as replacements for damaged human tissue. Others have printed human tissue before, but they have been limited to thin slices of tissue about a third as thick as a dime. When scientists try to print thicker layers of tissue, cells on the interior starve for oxygen and nutrients, and have no good way of removing carbon dioxide and other waste. So they suffocate and die.

Nature gets around this problem by permeating tissue with a network of tiny, thin-walled blood vessels that nourish the tissue and remove waste, so Kolesky and Lewis set out to mimic this key function.

3D printing excels at creating intricately detailed 3D structures, typically from inert materials like plastic or metal. In the past, Lewis and her team have pioneered a broad range of novel inks that solidify into materials with useful electrical and mechanical properties. These inks enable 3D printing to go beyond form to embed functionality.

To print 3D tissue constructs with a predefined pattern, the researchers needed functional inks with useful biological properties, so they developed several "bio-inks" — tissue-friendly inks containing key ingredients of living tissues. One ink contained extracellular matrix, the biological material that knits cells into tissues. A second ink contained both extracellular matrix and living cells.

To create blood vessels, they developed a third ink with an unusual property: it melts as it is cools, rather than as it warms. This allowed the scientists to first print an interconnected network of filaments, then melt them by chilling the material and suction the liquid out to create a network of hollow tubes, or vessels.

The Harvard team then road-tested the method to assess its power and versatility. They printed 3D tissue constructs with a variety of architectures, culminating in an intricately patterned construct containing blood vessels and three different types of cells – a structure approaching the complexity of solid tissues.

Moreover, when they injected human endothelial cells into the vascular network, those cells regrew the blood-vessel lining. Keeping cells alive and growing in the tissue construct represents an important step toward printing human tissues. "Ideally, we want biology to do as much of the job of as possible," Lewis said.

Lewis and her team are now focused on creating functional 3D tissues that are realistic enough to screen drugs for safety and effectiveness. "That's where the immediate potential for impact is," Lewis said.

Scientists could also use the printed tissue constructs to shed light on activities of living tissue that require complex architecture, such as wound healing, blood vessel growth, or tumor development.

"Tissue engineers have been waiting for a method like this," said Don Ingber, M.D., Ph.D., Wyss Institute Founding Director. "The ability to form functional vascular networks in 3D tissues before they are implanted not only enables thicker tissues to be formed, it also raises the possibility of surgically connecting these networks to the natural vasculature to promote immediate perfusion of the implanted tissue, which should greatly increase their engraftment and survival".

In addition to Lewis and Kolesky, the Wyss Institute research team also included Ryan L. Truby, A. Sydney Gladman, Travis A. Busbee, SEAS graduate students, and Kimberly A. Homan, Ph.D., a postdoctoral fellow at SEAS. The work was funded by the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering and the Harvard Materials Research Science and Engineering Center.

INFORMATION:

PRESS CONTACT

Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University

Dan Ferber

dan.ferber@wyss.harvard.edu

+1 617-432-1547

IMAGES AND VIDEO AVAILABLE

About the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University

The Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University uses Nature's design principles to develop bioinspired materials and devices that will transform medicine and create a more sustainable world. Working as an alliance among Harvard's Schools of Medicine, Engineering, and Arts & Sciences, and in partnership with Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston Children's Hospital, Dana Farber Cancer Institute, Massachusetts General Hospital, the University of Massachusetts Medical School, Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital, Boston University, Tufts University, and Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin, the Institute crosses disciplinary and institutional barriers to engage in high-risk research that leads to transformative technological breakthroughs. By emulating Nature's principles for self-organizing and self-regulating, Wyss researchers are developing innovative new engineering solutions for healthcare, energy, architecture, robotics, and manufacturing. These technologies are translated into commercial products and therapies through collaborations with clinical investigators, corporate alliances, and new start-ups.

About the Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences

The Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS) serves as the connector and integrator of Harvard's teaching and research efforts in engineering, applied sciences, and technology. Through collaboration with researchers from all parts of Harvard, other universities, and corporate and foundational partners, we bring discovery and innovation directly to bear on improving human life and society. For more information, visit: http://seas.harvard.edu

An essential step toward printing living tissues

New method enables scientists to print tissue constructs with blood vessels

2014-02-19

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Antidepressant holds promise in treating Alzheimer's agitation

2014-02-19

Feb. 19, 2014 (Toronto) - An antidepressant medication has shown potential in treating symptoms of agitation that occur with Alzheimer's disease and in alleviating caregivers' stress, according to a multi-site U.S.- Canada study.

"Up to 90 per cent of people with dementia experience symptoms of agitation such as emotional distress, restlessness, aggression or irritability, which is upsetting for patients and places a huge burden on their caregivers," said Dr. Bruce G. Pollock, Vice President of Research at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH), who directed ...

'Beautiful but sad' music can help people feel better

2014-02-19

New research from psychologists at the universities of Kent and Limerick has found that music that is felt to be 'beautiful but sad' can help people feel better when they're feeling blue.

The research investigated the effects of what the researchers described as Self-Identified Sad Music (SISM) on people's moods, paying particular attention to their reasons for choosing a particular piece of music when they were experiencing sadness - and the effect it had on them.

The study identified a number of motives for sad people to select a particular piece of music they perceive ...

Stratification determines the fate of fish stocks in the Baltic Sea

2014-02-19

With its narrow connection to the North Sea, strong currents, a large number of river estuaries and a bottom profile marked by ridges, basins and troughs, the Baltic represents an inland sea with highly different water qualities. The fact that these morphological and hydrographic conditions can also influence the fate of fish stocks has now been shown by a team of fisheries biologists from GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel and the National Institute of Aquatic Resources (DTU Aqua) at the Technical University of Denmark. For their publication in the international ...

Dreams, deja vu and delusions caused by faulty 'reality testing'

2014-02-19

New research from the University of Adelaide has delved into the reasons why some people are unable to break free of their delusions, despite overwhelming evidence explaining the delusion isn't real.

In a new paper published in the journal Frontiers in Psychology, University of Adelaide philosopher Professor Philip Gerrans says dreams and delusions have a common link – they are associated with faulty "reality testing" in the brain's higher order cognitive systems.

"Normally this 'reality testing' in the brain monitors a 'story telling' system which generates a narrative ...

A challenge to the genetic interpretation of biology

2014-02-19

A proposal for reformulating the foundations of biology, based on the 2nd law of thermodynamics and which is in sharp contrast to the prevailing genetic view, is published today in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface under the title "Genes without prominence: a reappraisal of the foundations of biology". The authors, Arto Annila, Professor of physics at Helsinki University and Keith Baverstock, Docent and former professor at the University of Eastern Finland, assert that the prominent emphasis currently given to the gene in biology is based on a flawed interpretation ...

Two new butterfly species discovered in eastern USA

2014-02-19

Butterflies are probably best-loved insects. As such, they are relatively well studied, especially in the United States. Eastern parts of the country are explored most thoroughly. First eastern US butterfly species were described by the father of modern taxonomy Carl Linnaeus himself, over 250 years ago. For the last two and a half centuries, naturalists have been cataloguing species diversity of eastern butterflies, and every nook and cranny has been searched. Some even say that we learned everything there is to know about taxonomy of these butterflies.

Discovery of ...

Targeted treatment for ovarian cancer discovered

2014-02-19

Researchers at Women & Infants Hospital of Rhode Island have developed a biologic drug that would prevent the production of a protein known to allow ovarian cancer cells to grow aggressively while being resistant to chemotherapy. This would improve treatment and survival rates for some women.

The work coming out of the molecular therapeutic laboratory directed by Richard G. Moore, MD, entitled "HE4 (WFDC2) gene overexpression promotes ovarian tumor growth" was recently published in the international science journal Scientific Reports, a Nature publishing group.

"We ...

UNH research: Most of us have made best memories by age 25

2014-02-19

DURHAM, N.H. – By the time most people are 25, they have made the most important memories of their lives, according to new research from the University of New Hampshire.

Researchers at UNH have found that when older adults were asked to tell their life stories, they overwhelmingly highlighted the central influence of life transitions in their memories. Many of these transitions, such as marriage and having children, occurred early in life.

"When people look back over their lives and recount their most important memories, most divide their life stories into chapters ...

How stick insects honed friction to grip without sticking

2014-02-19

When they're not hanging upside down, stick insects don't need to stick. In fact, when moving upright, sticking would be a hindrance: so much extra effort required to 'unstick' again with every step.

Latest research from Cambridge's Department of Zoology shows that stick insects have specialised pads on their legs designed to produce large amounts of friction with very little pressure. When upright, stick insects aren't sticking at all, but harnessing powerful friction to ensure they grip firmly without the need to unglue themselves from the ground when they move. ...

Addicted to tanning?

2014-02-19

BOWLING GREEN, O.—They keep tanning, even after turning a deep brown and experiencing some of the negative consequences. Skin cancer is among the most common, preventable types of the disease, yet many continue to tan to excess.

Research from Lisham Ashrafioun, a Bowling Green State University Ph.D. student in psychology, and Dr. Erin Bonar, an assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of Michigan Addiction Research Center and a BGSU alumna, shows that some who engage in excessive tanning may also be suffering from obsessive-compulsive (OCD) and body dysmorphic ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Engineers sharpen gene-editing tools to target cystic fibrosis

Pets can help older adults’ health & well-being, but may strain budgets too

First evidence of WHO ‘critical priority’ fungal pathogen becoming more deadly when co-infected with tuberculosis

World-first safety guide for public use of AI health chatbots

Women may face heart attack risk with a lower plaque level than men

Proximity to nuclear power plants associated with increased cancer mortality

Women’s risk of major cardiac events emerges at lower coronary plaque burden compared to men

Peatland lakes in the Congo Basin release carbon that is thousands of years old

Breadcrumbs lead to fossil free production of everyday goods

New computation method for climate extremes: Researchers at the University of Graz reveal tenfold increase of heat over Europe

Does mental health affect mortality risk in adults with cancer?

EANM launches new award to accelerate alpha radioligand therapy research

Globe-trotting ancient ‘sea-salamander’ fossils rediscovered from Australia’s dawn of the Age of Dinosaurs

Roadmap for Europe’s biodiversity monitoring system

Novel camel antimicrobial peptides show promise against drug-resistant bacteria

Scientists discover why we know when to stop scratching an itch

A hidden reason inner ear cells die – and what it means for preventing hearing loss

Researchers discover how tuberculosis bacteria use a “stealth” mechanism to evade the immune system

New microscopy technique lets scientists see cells in unprecedented detail and color

Sometimes less is more: Scientists rethink how to pack medicine into tiny delivery capsules

Scientists build low-cost microscope to study living cells in zero gravity

The Biophysical Journal names Denis V. Titov the 2025 Paper of the Year-Early Career Investigator awardee

Scientists show how your body senses cold—and why menthol feels cool

Scientists deliver new molecule for getting DNA into cells

Study reveals insights about brain regions linked to OCD, informing potential treatments

Does ocean saltiness influence El Niño?

2026 Young Investigators: ONR celebrates new talent tackling warfighter challenges

Genetics help explain who gets the ‘telltale tingle’ from music, art and literature

Many Americans misunderstand medical aid in dying laws

Researchers publish landmark infectious disease study in ‘Science’

[Press-News.org] An essential step toward printing living tissuesNew method enables scientists to print tissue constructs with blood vessels