(Press-News.org) MANHATTAN, KAN. -- A Kansas State University epidemiologist is helping cats, pet owners and soldiers stay healthy by studying feline tularemia and the factors that influence its prevalence.

Ram Raghavan, assistant professor of diagnostic medicine and pathobiology, and collaborative researchers have found that a certain combination of climate, physical environment and socio-ecologic conditions are behind tularemia infections among cats in the region. More than 50 percent of all tularemia cases in the U.S. occur in Kansas, Missouri, Oklahoma and Arkansas, Raghavan said.

Francisella tularensis, a bacterium that causes tularemia, commonly circulates among ticks, rabbits and rodents in the wild, but also frequently infects domestic cats. Tularemia is a zoonotic disease that can spread to humans through ticks or insect bites, eating undercooked rabbit meat, close contact with infected animals or even through airborne means. If left untreated, it can cause death in humans and animals, Raghavan said.

While it is not known exactly how many human tularemia cases are caused by exposure to infected cats, it is possible for cats to transmit the disease to owners through bites and scratches. Cats also can be reliable sentinels for recognizing disease activity in the environment. If cats hunt outdoors or come into contact with an infected rabbit or animal, they can bring tularemia back to their owners.

Raghavan's research so far has found that tularemia is more likely to appear:

In newly urbanized areas.

In residential locations surrounded by grassland.

In high-humidity environments. Raghavan found that locations where tularemia was confirmed had high-humidity conditions about eight weeks before the disease appeared.

For the research, Raghavan is partnering with the university's geography department and the Public Health Department of Fort Riley Medical Activity. Raghavan maps tularemia cases confirmed by the Kansas State Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory and then collaborates with John Harrington Jr. and Doug Goodin -- both professors of geography -- to compile geospatial data for tularemia locations. By bringing in layers of data the researchers are determining how different influential factors -- such as climate, land cover, landscape and pet owners' economic conditions -- can lead to feline tularemia.

"Taking a multidisciplinary and computational approach helps us quickly understand the disease and make new discoveries," Raghavan said. "We use diagnostic information collected over time at the Kansas State Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory and a wealth of extremely useful information from NASA and other agencies. We can then put all these data in a framework where it is useful for public health and animal health."

While tularemia is more common in young children and men, people also can get the disease when mowing lawns in a contaminated area, Raghavan said. Both human and feline tularemia cases peak through late spring and summer -- when the weather is warmer, more ticks are present and more people are outside. Tularemia cases decrease at summer's end.

"Climate plays such a huge role in zoonotic diseases," Raghavan said. "With all the talk about climate change, we need to know if there are any significant climate effects that are causing tularemia cases to increase."

Tularemia also poses concerns for the military and soldiers during training exercises, whether they are training in U.S. bases or bases around the world. During training, soldiers are actively engaged in the environment and that increases the risk of tularemia infection.

"They could be crawling on the ground and may come in contact with a dead animal or rabbit that was infected with tularemia," Raghavan said. "The soldiers also can be bitten by ticks. All it takes is a few bacteria to cause infection."

Because of the low infection dose of organisms, it is even more important to understand tularemia because of its potential as a bioterrorism tool, Raghavan said.

"If a little of the bacteria was present in the form of an aerosol, it could be released in a crowded area and potentially infect a lot of people very quickly," Raghavan said. "Because it is such a rare disease, not everyone is prepared for it, even though the treatments are very simple. Untreated infections can cause death."

Symptoms of tularemia in humans may include fever, swelling of lymph nodes, skin ulcers near tick bites, or cough, chest pain and difficulty breathing in more serious cases. Clinical signs in cats include lethargy, anorexia and fever. People should contact their doctor or their veterinarian if they observe tularemia symptoms, Raghavan said.

INFORMATION:

The researchers recently published their work in the journal of Vector Borne and Zoonotic Diseases. Raghavan also is collaborating with Dan Andresen, associate professor of computing and information sciences at Kansas State University, and is using the university's high-performance computing cluster, Beocat, to run simulations. Raghavan received support from the National Science Foundation Experimental Program to Stimulate Competitive Research, or EPSCoR.

Research prevents zoonotic feline tularemia by finding influential geospatial factors

2014-02-19

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Infants with leukemia inherit susceptibility

2014-02-19

Babies who develop leukemia during the first year of life appear to inherit an unfortunate combination of genetic variations that can make the infants highly susceptible to the disease, according to a new study at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis and the University of Minnesota.

The research is available online in the journal Leukemia.

Doctors have long puzzled over why it is that babies just a few months old sometimes develop cancer. As infants, they have not lived long enough to accumulate a critical number of cancer-causing mutations.

"Parents ...

NASA satellite sees a ragged eye develop in Tropical Cyclone Guito

2014-02-19

NASA satellite data was an "eye opener" when it came to Tropical Cyclone 15S, now known as Guito in the Mozambique Channel today, Feb. 19, 2014. NASA's Aqua satellite passed over Guito and visible imagery revealed a ragged eye had developed as the tropical cyclone intensified.

The Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer or MODIS instrument aboard NASA's Aqua satellite captured a visible image of Tropical Cyclone Guito on Feb. 19 at 1140 UTC/6:40 a.m. EST as it continued moving south through the Mozambique Channel. The image revealed a ragged-looking eye with a band ...

Surveys find that despite economic challenges Malagasy fishers support fishing regulations

2014-02-19

Scientists from the Wildlife Conservation Society, the ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies, and other groups have found that the fishing villages of Madagascar—a country with little history of natural resource regulation—are generally supportive of fishing regulations, an encouraging finding that bodes well for sustainable strategies needed to reduce poverty in the island nation.

Specifically, Malagasy fishers perceive restrictions on certain kinds of fishing gear as being beneficial for their livelihoods, according to the results of a survey conducted with ...

Kessler Foundation researchers study impact of head movement on fMRI data

2014-02-19

West Orange, NJ. February 19, 2014. Kessler Foundation researchers have shown that discarding data from subjects with multiple sclerosis (MS) who exhibit head movement during functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) may bias sampling away from subjects with lower cognitive ability. The study was published in the January issue of Human Brain Mapping. (Wylie GR, Genova H, DeLuca J, Chiaravalloti N, Sumowski JF. Functional MRI movers and shakers: Does subject-movement cause sampling bias.) Glenn Wylie, DPhil, is associate director of Neuroscience in Neuropsychology & Neuroscience ...

Clouds seen circling supermassive black holes

2014-02-19

Astronomers see huge clouds of gas orbiting supermassive black holes at the centers of galaxies. Once thought to be a relatively uniform, fog-like ring, the accreting matter instead forms clumps dense enough to intermittently dim the intense radiation blazing forth as these enormous objects condense and consume matter, they report in a paper to be published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, available online now.

Video depicting the swirling clouds is posted to YouTube http://youtu.be/QA8nzRkjOEw

Evidence for the clouds comes from records collected ...

Better cache management could improve chip performance, cut energy use

2014-02-19

Computer chips keep getting faster because transistors keep getting smaller. But the chips themselves are as big as ever, so data moving around the chip, and between chips and main memory, has to travel just as far. As transistors get faster, the cost of moving data becomes, proportionally, a more severe limitation.

So far, chip designers have circumvented that limitation through the use of "caches" — small memory banks close to processors that store frequently used data. But the number of processors — or "cores" — per chip is also increasing, which makes cache management ...

When faced with a hard decision, people tend to blame fate

2014-02-19

Life is full of decisions. Some, like what to eat for breakfast, are relatively easy. Others, like whether to move cities for a new job, are quite a bit more difficult. Difficult decisions tend to make us feel stressed and uncomfortable – we don't want to feel responsible if the outcome is less than desirable. New research suggests that we deal with such difficult decisions by shifting responsibility for the decision to fate.

The findings are published in Psychological Science, a journal of the Association for Psychological Science.

"Fate is a ubiquitous supernatural ...

UK failing to harness its bioenergy potential

2014-02-19

The UK could generate almost half its energy needs from biomass sources, including household waste, agricultural residues and home-grown biofuels by 2050, new research suggests.

Scientists from the Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research at The University of Manchester found that the UK could produce up to 44% of its energy by these means without the need to import.

The study, published in Energy Policy journal, highlights the country's potential abundance of biomass resources that are currently underutilised and totally overlooked by the bioenergy sector. Instead, ...

Making nanoelectronics last longer for medical devices, 'cyborgs'

2014-02-19

The debut of cyborgs who are part human and part machine may be a long way off, but researchers say they now may be getting closer. In a study published in ACS' journal Nano Letters, they report development of a coating that makes nanoelectronics much more stable in conditions mimicking those in the human body. The advance could also aid in the development of very small implanted medical devices for monitoring health and disease.

Charles Lieber and colleagues note that nanoelectronic devices with nanowire components have unique abilities to probe and interface with living ...

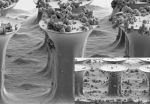

Gecko-inspired adhesion: Self-cleaning and reliable

2014-02-19

This news release is available in German. Geckos outclass adhesive tapes in one respect: Even after repeated contact with dirt and dust do their feet perfectly adhere to smooth surfaces. Researchers of the KIT and the Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, have now developed the first adhesive tape that does not only adhere to a surface as reliably as the toes of a gecko, but also possesses similar self-cleaning properties. Using such a tape, food packagings or bandages might be opened and closed several times. The results are published in the "Interface" journal of ...