(Press-News.org) When deciding what materials to use in building something, determining how those materials respond to stress and strain is often the first task. A material's macroscopic, or bulk, properties in this area — whether it can spring back into shape, for example — is generally the product of what is happening on a microscopic scale. When stress causes a material's constituent molecules to rearrange in a way such that they can't go back to their original positions, it is known as "plastic deformation."

Researchers at the University of Pennsylvania have devised a method to study stress at the macro and micro scales at the same time, using a model system in which microscopic particles stand in for molecules. This method has allowed the researchers to demonstrate an unusual hybrid behavior in their model material: a reversible rearrangement of its particles that nevertheless has the characteristics of plastic deformation on the macroscale. That kind of plastic deformation is more akin to what happens with ketchup or toothpaste, a liquid-like flowing instead of a brittle fracturing of the material's particles.

Their study could pave the way for designing this potentially useful trait into new materials. Plastic deformation dissipates energy rather than transferring it, so a material that could repeatedly deform in this way could be used to dampen vibrations or protect against impacts.

The study was conducted by postdoctoral researcher Nathan Keim and professor Paulo Arratia, both of the Department of Mechanical Engineering and Applied Mechanics in Penn's School of Engineering and Applied Science. It was published in Physical Review Letters.

"If you're driving your car and you hit a lamppost, your car would be totally deformed," Arratia said. "That's plastic deformation because it's irreversible. When you put your car into reverse and back up away from the lamppost, it's not as if the car just springs back into shape. And even if you take it to the body shop and hammer it out to look like new, it's never going to be the same again on the atomic level."

"On the other end of the spectrum," Keim said, "there's elastic deformation. Those deformations are usually reversible rearrangements. If you take a piece of steel and deform it just a little bit, like sitting on the hood of your car rather than running it into a lamppost, it will come back exactly as it started, even on the microstructural level.

"What we were able to show with this model is that you can have something that's between the two ends of this spectrum, a hybrid regime that is plastic but also reversible."

Simultaneously investigating both the macroscopic and microscopic behavior of a material under stress time is a challenge: bulk materials are generally opaque, so seeing what is happening inside of them while they maintain their bulk properties is impossible. To provide a window to this inner world, the researchers built a model material that sacrifices complexity for access.

"The complexity we sacrificed is the third dimension," Keim said. "We have made an effectively 2-D material in the lab that consists of microscopic particles that sit on an oil-water interface. These particles have a little electric charge that keeps them constantly pushing away from each other, which means you can think of them as drops of liquid in an emulsion or even as atoms."

The researchers used this model material to study a behavior known as the "yielding transition," which is how disordered solids begin to flow. Just as toothpaste doesn't immediately flow out of the tube and ketchup doesn't pour out of the bottle once the cap is removed, the particles of a disordered solid are jammed against one another and don't easily rearrange themselves unless outside energy is added.

In the case of ketchup, this outside energy often takes the form of tapping the side of the bottle. In the case of this model material, the researchers added this energy by way of a needle that also sat at the material's oil-water interface, in the plane with the rest of the particles. Using an electromagnetic field, they could swing the needle back and forth against the particles and measure how much resistance they provided.

In experimenting with this model material, the researchers were surprised by what they described as a "learned behavior." They found that by repeatedly moving the needle back and forth, irreversibly deforming the material many times, the particles eventually rearranged themselves in such a way that they went back to their original state after each cycle of deformation.

"The material can reorganize itself so that the link between plasticity and irreversibility is broken," Arratia said. "The material flows slightly, and yet, at the end of each cycle, it is exactly unchanged."

Critically, this reversible rearrangement of particles is not like what happens in elastic deformations.

"After the material is deformed," Keim said, "it doesn't just bounce back to its original state. Rather than just pushing back elastically, like a spring would, it gives a little bit and dissipates energy, more like a viscous fluid than a solid."

Having a mix of plastic and elastic properties is potentially useful.

"You might want this in materials where the alternative to flowing is shattering," Keim said. "You'd rather that it deform a little bit before breaking, and you'd also want things not to be severely altered or damaged by being deformed again and again. This kind of plastic deformation also dissipates a lot more energy; you want the body of your car to absorb the energy of an impact and dissipate it, not transfer it to you."

While this behavior has now only been observed in the researchers' model material, understanding the conditions in which it arises could lead to ways of producing it in materials that might be used outside the lab.

"We are designing for failure," Arratia said. "Elastic deformation is pretty great, but it can't last forever, eventually something has to give. And when it gives, this would be a pretty great way to do it. You'd like that transition to be as graceful and non-destructive as possible."

INFORMATION:

The research was supported by the National Science Foundation through Penn's Materials Science Research and Engineering Center.

Penn researchers 'design for failure' with model material

2014-02-24

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Parents' attitudes about helping their grown children affect their mental health

2014-02-24

Older parents frequently give help to their middle-aged offspring, and their perceptions about giving this help may affect their mental health, according to a team of researchers.

"We usually view the elderly as needy, but our research shows that parents ages 60 and over are giving help to their children, and this support is often associated with lower rates of depression among the older adults," said Lauren Bangerter, Ph.D. student in human development and family studies, Penn State.

The team -- which included researchers at Penn State, the University of Texas ...

Specialized cognitive therapy improves blood sugar control in depressed diabetes patients

2014-02-24

Although maintaining good blood sugar control is crucial for avoiding complications of diabetes, it has been estimated that only about half of patients are successful in meeting target blood glucose levels. The prevalence of depression among diabetes patients – up to twice as high as in the general population – can interfere with patients' ability to manage their diabetes. Now a group of Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) investigators report that a program of cognitive behavioral therapy that addresses both mood and diabetes self-care led to improved blood sugar control ...

Almost 200 new species of parasitoid wasps named after local parataxonomists in Costa Rica

2014-02-24

An inventory of wild-caught caterpillars, its food plants and parasitoids, has been going on for more than 34 years in Area de Conservación Guanacaste (ACG), a protected area of approximately 1200 km2 in northwestern Costa Rica. As a result, more than 10,000 species of moths and butterflies are estimated to live in ACG. Their caterpillars are in turn attacked by many parasitoid wasps, also numbering thousands of species. However, most of those wasps have never been described and remain unknown.

For the past few years researchers from Canada, Costa Rica and the United ...

New technology detect cellular memory

2014-02-24

Cells in our body are constantly dividing to maintain our body functions. At each division, our DNA code and a whole machinery of supporting components has to be faithfully duplicated to maintain the cell's memory of its own identity. Researchers at BRIC, University of Copenhagen, have developed a new technology that has revealed the dynamic events of this duplication process and the secrets of cellular memory. The results are published in Nature Cell Biology.

In 2009, two women at BRIC, University of Copenhagen joined forces to develop a new technology that could elucidate ...

Researchers make the invisible visible

2014-02-24

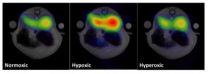

The 2003 development of the so-called hyperpolarization technique by a Danish research was a groundbreaking moment that made it possible to see all the body's cells with the help of a new contrast agent for MRI scans. Researchers from Aarhus have now taken another big step towards understanding the body's cells and with it also the development of diseases:

"With the hyperpolarization method, sensitivity to specific contrast agents is up to 10,000 times higher than with a traditional MRI scanning. What we have now documented is that with the hyperpolarization MRI scanning ...

Team converts sugarcane to a cold-tolerant, oil-producing crop

2014-02-24

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — A multi-institutional team reports that it can increase sugarcane's geographic range, boost its photosynthetic rate by 30 percent and turn it into an oil-producing crop for biodiesel production.

These are only the first steps in a bigger initiative that will turn sugarcane and sorghum – two of the most productive crop plants known – into even more productive, oil-generating plants.

The team will present its latest findings Tuesday (Feb. 25) at the U.S. Department of Energy's ARPA-E Energy Innovation Summit in Washington, D.C.

"Biodiesel is attractive ...

Pointing is infants' first communicative gesture

2014-02-24

VIDEO:

Catalan researchers have studied the acquisition and development of language in babies on the basis of the temporary coordination of gestures and speech. The results are the first in showing...

Click here for more information.

Catalan researchers have studied the acquisition and development of language in babies on the basis of the temporary coordination of gestures and speech. The results are the first in showing how and when they acquire the pattern of coordination ...

The chemistry of Sriracha: Hot sauce science

2014-02-24

WASHINGTON, Feb. 24, 2014 — Forget ketchup and mustard — Sriracha might be the world's new favorite condiment. Beloved by millions for its unique spicy, garlicky, slightly sweet flavor, the chemistry of "rooster sauce" is the subject of the American Chemical Society's latest Reactions video. The video is available at http://youtu.be/U2DJN0gnuI8.

INFORMATION:

Subscribe to the series at Reactions YouTube, and follow us on Twitter @ACSreactions to be the first to see our latest videos.

The American Chemical Society is a nonprofit organization chartered by the U.S. ...

Uninsured adolescents and young adults more likely to be diagnosed with advanced cancer

2014-02-24

ATLANTA – February 24, 2014 – A new American Cancer Society study shows that uninsured adolescents and young adults were far more likely to be diagnosed with late-stage cancer, which is more difficult and expensive to treat and more deadly, compared to young patients with health insurance. The study, published early online, will appear in the March issue of the journal CANCER.

The study's authors says their data suggest a way forward for cancer control efforts in the adolescent and young adult (AYA) population, a group that has benefited the least from recent progress ...

Creating animated characters outdoors

2014-02-24

This news release is available in German.

So far, film studios have had to put in huge amounts of effort to set monsters, superheroes, fairies or other virtual characters into real feature film scenes. Within the so-called motion capturing process, real actors wear skintight suits with markers on them. These suits reflect infrared light that is emitted and captured by special cameras. Subsequent to this, the movements of the actors are rendered with the aid of software into animated characters. The most popular example of this is "Gollum" from the film Lord of the ...