(Press-News.org) This news release is available in German.

Most children ill with fever in Tanzania suffer from a viral infection, a new study published in the New England Journal of Medicine shows. A research team led by Dr. Valérie D'Acremont from the Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute in Basel and the Policlinique Médicale Universitaire in Lausanne systematically assessed the causes of febrile illnesses in Tanzanian children. According to the results, in most cases a treatment with antimalarials or antibiotics is not required. The finding has the potential to improve the rational use of antimicrobials, and thus reduce costs and drug resistance.

In many African countries, sick children with fever are still believed to suffer from malaria. Fortunately, rapid and reliable diagnostic tools make malaria relatively easy to diagnose today. This is less true for other febrile illnesses that are potentially severe and for which a specific treatment is required.

For the first time, scientists from the Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute (Swiss TPH) in Basel and the Policlinique Médicale Universitaire in Lausanne, in collaboration with the Geneva University Hospitals, the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Geneva and the Tanzanian Ministry of Health attempted a comprehensive screening of Tanzanian children diagnosed with fever. The team led by Dr. Valérie D'Acremont analysed clinical field-data and the results of over 25'000 laboratory tests, using a complex algorithm. This allowed differentiating the bacterial, parasitic or viral causes for the children's fever episode.

The results show that in half of the cases children suffered from acute respiratory infections mostly due to viruses, in particular influenza. For the other children, malaria and bacterial infections were rare and most of them had also a viral infection. Neither an antimalarial nor an antibiotic treatment is required in these cases.

Antibiotic resistance as a major public health concern

These results are highly relevant for patient management and public health measures. Treatments with antibiotics and the development of resistance against them is one of the major public health problems not only in Africa, but worldwide. In Europe, i.e., resistance against antibiotics is a growing threat.

"When a child has a febrile illness, antibiotic should thus only be used in limited and specific situations that can be identified by a health professional" underscores Valérie D'Acremont. The study represents a milestone in helping health personnel in resource-limited countries to better gauge these specific situations and provide the best possible treatment for their feverish patients.

INFORMATION:

The study is published in the New England Journal of Medicine on February 27th 2014.

Supported by grants from the Swiss National Science

Foundation (3270B0-109696, to Dr. Lengeler; IZ70Z0-124023, to Dr. Genton; and 32003B_127160, to Dr. Kaiser), the Commission for International Medicine of the University Hospital of Geneva, and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

Valérie D'Acremont, Mary Kilowoko, Esther Kyungu, Sister Philipina, Willy Sangu, Judith Kahama-Maro, Christian Lengeler, Pascal Cherpillod, Laurent Kaiser, Blaise Genton. Beyond Malaria: Causes of Fever in Outpatient Tanzanian children. N Engl J Med 370;9 February 27, 2014.

Contacts

Valérie D'Acremont, Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute & PMU Lausanne

Valerie.Dacremont@unibas.ch, Tel +41 79 556 25 51

Willy Sangu, Disctrict Medical Office, Municipality of Ilala, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania

wsangu@yahoo.com, Tel +255 784 92 58 40

Katarzyna Gornik Verselle, Communication, Policlinique médicale universitaire Lausanne

Katarzyna.Gornik-Verselle@hospvd.ch, Tel +41 21 314 08 39 / Tel +41 79 556 67 74

Christian Heuss, Communication, Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute

christian.heuss@unibas.ch, Tel +41 61 284 86 83

About the Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute (Swiss TPH)

The Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute (Swiss TPH) is one of Switzerland's leading public and global health institutions. Associated with the University of Basel, the Institute combines re-search, teaching and service provision at local, national and international level. The Swiss TPH is a public sector organisation and receives around 17% of its budget of approximately 80 million francs from core contributions from the cantons of Basel-Stadt and Basel-Landschaft (10%) and from the federal government (8%). The remainder (82%) is acquired by competing for funds. The Institute has more than 600 employees working in 20 countries. Professor Marcel Tanner is head of the Institute.

Febrile illnesses in children most often due to viral infections

2014-02-27

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

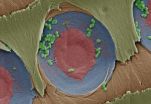

Breast cancer cells less likely to spread when one gene is turned off

2014-02-27

COLUMBUS, Ohio – New research suggests that a protein only recently linked to cancer has a significant effect on the risk that breast cancer will spread, and that lowering the protein's level in cell cultures and mice reduces chances for the disease to extend beyond the initial tumor.

The team of medical and engineering researchers at The Ohio State University previously determined that modifying a single gene to reduce this protein's level in breast cancer cells lowered the cells' ability to migrate away from the tumor site.

In a new study published in the journal ...

One gene influences recovery from traumatic brain injury

2014-02-27

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — Researchers report that one change in the sequence of the BDNF gene causes some people to be more impaired by traumatic brain injury (TBI) than others with comparable wounds.

The study, described in the journal PLOS ONE, measured general intelligence in a group of 156 Vietnam War veterans who suffered penetrating head wounds during the war. All of the study subjects had damage to the prefrontal cortex, a brain region behind the forehead that is important to cognitive tasks such as planning, problem-solving, self-restraint and complex thought.

The ...

Caesarean babies are more likely to become overweight as adults

2014-02-27

Babies born by caesarean section are more likely to be overweight or obese as adults, according to a new analysis.

The odds of being overweight or obese are 26 per cent higher for adults born by caesarean section than those born by vaginal delivery, the study found (see footnote).

The finding, reported in the journal PLOS ONE, is based on combined data from 15 studies with over 38,000 participants.

The researchers, from Imperial College London, say there are good reasons why many women should have a C-section, but mothers choosing a caesarean should be aware that ...

Cows are smarter when raised in pairs

2014-02-27

Cows learn better when housed together, which may help them adjust faster to complex new feeding and milking technologies on the modern farm, a new University of British Columbia study finds.

The research, published today in PLOS ONE, shows dairy calves become better at learning when a "buddy system" is in place. The study also provides the first evidence that the standard practice of individually housing calves is associated with certain learning difficulties.

"Pairing calves seems to change the way these animals are able to process information," said Dan Weary, corresponding ...

Impact on mummy skull suggests murder

2014-02-27

Blunt force trauma to the skull of a mummy with signs of Chagas disease may support homicide as cause of death, which is similar to previously described South American mummies, according to a study published February 26, 2014 in PLOS ONE by Stephanie Panzer from Trauma Center Murau, Germany, and colleagues, a study that has been directed by the paleopathologist Andreas Nerlich from Munich University.

For over a hundred years, the unidentified mummy has been housed in the Bavarian State Archeological Collection in Germany. To better understand its origin and life history, ...

Tree branch filters water

2014-02-27

A small piece of freshly cut sapwood can filter out more than 99 percent of the bacteria E. coli from water, according to a paper published in PLOS ONE on February 26, 2014 by Michael Boutilier and Jongho Lee and colleagues from MIT.

Researchers were interested in studying low-cost and easy-to-make options for filtering dirty water, a major cause of human mortality in the developing world. The sapwood of pine trees contains xylem, a porous tissue that moves sap from a tree's roots to its top through a system of vessels and pores. To investigate sapwood's water-filtering ...

Waterbirds' hunt aided by specialized tail

2014-02-27

The convergent evolution of tail shapes in diving birds may be driven by foraging style, according to a paper published in PLOS ONE on February 26, 2014 by Ryan Felice and Patrick O'Connor from Ohio University.

Birds use their wings and specialized tail to maneuver through the air while flying. It turns out that the purpose of a bird's tail may have also aided in their diversification by allowing them to use a greater variety of foraging strategies. To better understand the relationship between bird tail shape and foraging strategy, researchers examined the tail skeletal ...

MIT researchers make a water filter from the sapwood in tree branches

2014-02-27

If you've run out of drinking water during a lakeside camping trip, there's a simple solution: Break off a branch from the nearest pine tree, peel away the bark, and slowly pour lake water through the stick. The improvised filter should trap any bacteria, producing fresh, uncontaminated water.

In fact, an MIT team has discovered that this low-tech filtration system can produce up to four liters of drinking water a day — enough to quench the thirst of a typical person.

In a paper published this week in the journal PLoS ONE, the researchers demonstrate that a small ...

Study finds social-media messages grow terser during major events

2014-02-27

In the last year or two, you may have had some moments — during elections, sporting events, or weather incidents — when you found yourself sending out a flurry of messages on social media sites such as Twitter.

You are not alone, of course: Such events generate a huge volume of social-media activity. Now a new study published by researchers in MIT's Senseable City Lab shows that social-media messages grow shorter as the volume of activity rises at these particular times.

"This helps us better understand what is going on — the way we respond to things becomes faster ...

Humans have a poor memory for sound

2014-02-27

Remember that sound bite you heard on the radio this morning? The grocery items your spouse asked you to pick up? Chances are, you won't.

Researchers at the University of Iowa have found that when it comes to memory, we don't remember things we hear nearly as well as things we see or touch.

"As it turns out, there is merit to the Chinese proverb 'I hear, and I forget; I see, and I remember," says lead author of the study and UI graduate student, James Bigelow.

"We tend to think that the parts of our brain wired for memory are integrated. But our findings indicate ...