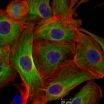

(Press-News.org) An essential weapon in the body's fight against infection has come into sharper view. Researchers at Princeton University have discovered the 3D structure of an enzyme that cuts to ribbons the genetic material of viruses and helps defend against bacteria.

The discovery of the structure of this enzyme, a first-responder in the body's "innate immune system," could enable new strategies for fighting infectious agents and possibly prostate cancer and obesity. The work was published Feb. 27 in the journal Science.

Until now, the research community has lacked a structural model of the human form of this enzyme, known as RNase L, said Alexei Korennykh, an assistant professor of molecular biology and leader of the team that made the discovery.

"Now that we have the human RNase L structure, we can begin to understand the effects of carcinogenic mutations in the RNase L gene. For example, families with hereditary prostate cancers often carry genetic mutations in the region, or locus, encoding RNase L," Korennykh said. The connection is so strong that the RNase L locus also goes by the name "hereditary prostate cancer 1." The newly found structure reveals the positions of these mutations and explains why some of these mutations could be detrimental, perhaps leading to cancer, Korennykh said. RNase L is also essential for insulin function and has been implicated in obesity.

The Princeton team's work has also led to new insights on the enzyme's function.

The enzyme is an important player in the innate immune system, a rapid and broad response to invaders that includes the production of a molecule called interferon. Interferon relays distress signals from infected cells to neighboring healthy cells, thereby activating RNase L to turn on its ability to slice through RNA, a type of genetic material that is similar to DNA. The result is new cells armed for destruction of the foreign RNA.

The 3D structure uncovered by Korennykh and his team consists of two nearly identical subunits called protomers. The researchers found that one protomer finds and attaches to the RNA, while the other protomer snips it.

The initial protomer latches onto one of the four "letters" that make up the RNA code, in particular, the "U," which stands for a component of RNA called uridine. The other protomer "counts" RNA letters starting from the U, skips exactly one letter, then cuts the RNA.

Although the enzyme can slice any RNA, even that of the body's own cells, it only does so when activated by interferon.

"We were surprised to find that the two protomers were identical but have different roles, one binding and one slicing," Korennykh said. "Enzymes usually have distinct sites that bind the substrate and catalyze reactions. In the case of RNase L, it appears that the same exact protein surface can do both binding and catalysis. One RNase L subunit randomly adopts a binding role, whereas the other identical subunit has no other choice but to do catalysis."

To discover the enzyme's structure, the researchers first created a crystal of the RNase L enzyme. The main challenge was finding the right combination of chemical treatments that would force the enzyme to crystallize without destroying it.

Korennykh groupAfter much trial and error and with the help of an automated system, postdoctoral research associate Jesse Donovan and graduate student Yuchen Han succeeded in making the crystals.

Next, the crystals were bombarded with powerful X-rays, which diffract when they hit the atoms in the crystal and form patterns indicative of the crystal's structure. The diffraction patterns revealed how the atoms of RNase L are arranged in 3D space.

At the same time Sneha Rath, a graduate student in Korennykh's laboratory, worked on understanding the RNA cleavage mechanism of RNase L using synthetic RNA fragments. Rath's results matched the structural findings of Han and Donovan, and the two pieces of data ultimately revealed how RNase L cleaves its RNA targets.

Han, Donovan and Rath contributed equally to the paper and are listed as co-first authors.

Finally, senior research specialist Gena Whitney and graduate student Alisha Chitrakar conducted additional studies of RNase L in human cells, confirming the 3D structure.

Now that the human structure has been solved, researchers can explore ways to either enhance or dampen RNase L activity for medical and therapeutic uses, Korennykh said.

"This work illustrates the wonderful usefulness of doing both crystallography and careful kinetic and enzymatic studies at the same time," said Peter Walter, professor of biochemistry and biophysics at the University of California-San Francisco School of Medicine. "Crystallography gives a static picture which becomes vastly enhanced by studies of the kinetics."

INFORMATION:

Support for the work was provided by Princeton University.

Han, Yuchen, Jesse Donovan, Sneha Rath, Gena Whitney, Alisha Chitrakar, and Alexei Korennykh. Structure of Human RNase L Reveals the Basis for Regulated RNA Decay in the IFN Response Science 1249845. Published online 27 February 2014 [DOI:10.1126/science.1249845]

It slices, it dices, and it protects the body from harm (Science)

2014-02-28

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Frequent childhood nightmares may indicate an increased risk of psychotic traits

2014-02-28

Children who suffer from frequent nightmares or bouts of night terrors may be at an increased risk of psychotic experiences in adolescence, according to new research from the University of Warwick.

The study, published today in the journal SLEEP, shows that children reporting frequent nightmares before the age of 12 were three and a half times more likely to suffer from psychotic experiences in early adolescence. Similarly, experiencing night terrors doubled the risk of such problems, including hallucinations, interrupted thoughts or delusions. Younger children, between ...

Study links poor sleep quality to reduced brain gray matter in Gulf War vets

2014-02-28

DARIEN, IL – A new study of Gulf War veterans found an association between poor sleep quality and reduced gray matter volume in the brain's frontal lobe, which helps control important processes such as working memory and executive function.

"Previous imaging studies have suggested that sleep disturbances may be associated with structural brain changes in certain regions of the frontal lobe," said lead author Linda Chao, associate adjunct professor in the Departments of Radiology and Biomedical Imaging and Psychiatry at the University of California, San Francisco. "The ...

Researchers identify brain differences linked to insomnia

2014-02-28

Johns Hopkins researchers report that people with chronic insomnia show more plasticity and activity than good sleepers in the part of the brain that controls movement.

"Insomnia is not a nighttime disorder," says study leader Rachel E. Salas, M.D., an assistant professor of neurology at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. "It's a 24-hour brain condition, like a light switch that is always on. Our research adds information about differences in the brain associated with it."

Salas and her team, reporting in the March issue of the journal Sleep, found that ...

UCLA study finds robotic-assisted prostate surgery offers better cancer control

2014-02-28

An observational study from UCLA's Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center has found that prostate cancer patients who undergo robotic-assisted prostate surgery have fewer instances of cancer cells at the edge of their surgical specimen and less need for additional cancer treatments like hormone or radiation therapy than patients who have traditional "open" surgery.

The study, published online Feb. 19 in the journal European Urology, was led by Dr. Jim Hu, UCLA's Henry E. Singleton Professor of Urology and director of robotic and minimally invasive surgery in the urology ...

Let there be tissue-penetrating light: Scientists develop new nanoscale method to fight cancer

2014-02-28

Researchers from UCLA's Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center have developed an innovative cancer-fighting technique in which custom-designed nanoparticles carry chemotherapy drugs directly to tumor cells and release their cargo when triggered by a two-photon laser in the infrared red wavelength.

The research findings by UCLA's Jeffrey Zink, a professor of chemistry and biochemistry, and Fuyu Tamanoi, a professor of microbiology, immunology and molecular genetics, and their colleagues were published online Feb. 20 in the journal Small and will appear in a later print ...

Robert Avery, D.O., M.S.C.E., studies innovations to improve vision in children with tumors

2014-02-28

Robert Avery, DO, MSCE, of Children's National Health System and colleagues are establishing innovative approaches with technology and medication to improve the vision of young children who have visual pathway glioma, a type of brain tumor.

Most optic pathway gliomas cause vision loss in children between one and eight years of age. As many as 20 percent of children with neurofibromatosis type 1 -- a genetic disorder that occurs in 1 in every 4,000 births – may develop these tumors. It is estimated that nearly half of those children may experience vision problems from ...

Tackling tumors with space station research

2014-02-28

In space, things don't always behave the way we expect them to. In the case of cancer, researchers have found that this is a good thing: some tumors seem to be much less aggressive in the microgravity environment of space compared to their behavior on Earth. This observation, reported in research published in February by the FASEB Journal, could help scientists understand the mechanism involved and develop drugs targeting tumors that don't respond to current treatments. This work is the latest in a large body of evidence on how space exploration benefits those of us on ...

Worm-like mite species discovered on Ohio State's campus

2014-02-28

COLUMBUS, Ohio – It looks like a worm and moves like a worm – sort of. But it is a previously unidentified microscopic species of mite that was discovered by a graduate student on The Ohio State University campus.

Affectionately dubbed the "Buckeye Dragon Mite" by Ohio State's Acarology Laboratory, the mite is officially named Osperalycus tenerphagus, Latin for "mouth purse" and "tender feeding," in a nod to its complex and highly unusual oral structure.

This mite doesn't resemble a mythological winged dragon, but the snake-like Chinese dancing dragons that appear in ...

3-D imaging sheds light on Apert syndrome development

2014-02-28

Three dimensional imaging of two different mouse models of Apert Syndrome shows that cranial deformation begins before birth and continues, worsening with time, according to a team of researchers who studied mice to better understand and treat the disorder in humans.

Apert Syndrome is caused by mutations in FGFR2 -- fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 -- a gene, which usually produces a protein that functions in cell division, regulation of cell growth and maturation, formation of blood vessels, wound healing, and embryonic development. With certain mutations, this gene ...

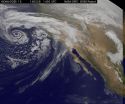

GOES-West satellite eyes soggy storm approaching California

2014-02-28

A swirling Eastern Pacific Ocean storm system headed for California was spotted by NOAA's GOES-West satellite on February 28. According to the National Weather Service, this storm system has the potential to bring heavy rainfall to the drought-stricken state.

The storm was captured using visible data from NOAA's GOES-West or GOES-15 satellite on Feb. 28 at 1430 UTC/6:30 a.m. PST was made into an image by NASA/NOAA's GOES Project at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md. The storm's center appeared as a tight swirl, with bands of clouds and showers already ...