(Press-News.org) Radio waves are used for many measurements and applications, for example, in communication with mobile phones, MRI scans, scientific experiments and cosmic observations. But 'noise' in the detector of the measuring instrument limits how sensitive and precise the measurements can be. Now researchers at the Niels Bohr Institute have developed a new method where they can avoid noise by means of laser light and can therefore achieve extreme precision of measurements. The results are published in the prestigious scientific journal, Nature.

'Noise' in the detector of a measuring instrument is first and foremost due to heat, that causes atoms and electrons to move chaotically, so the measurements become imprecise. The usual method to reduce noise in the detector of the measuring equipment is therefore to cool it down to 5-10 degrees Kelvin, which corresponds to approx. minus 265 degrees C. This is expensive and stille does not allow to measure the weakest signals.

"We have developed a detector that does not need to be cooled down, but which can operate at room temperature and yet hardly has any thermal noise. The only noise that fundamentally remains is so-called quantum noise, which is the minimal fluctuations of the laser light itself," explains Eugene Polzik, Professor and Head of the research center Quantop at the Niels Bohr Institute at the University of Copenhagen.

Optomechanical method

The method, called optomechanics, is a complex interaction between a mechanical movement and optical radiation.

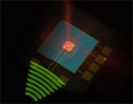

The experiment consists of an antenna, which picks up the radio waves, a capacitor and a laser beam. The antenna picks up the radio waves and transfers the signal to the capacitor, which is read by the laser beam - that is to say the capacitor and the laser beam make up the detector. But the capacitor is not an ordinary pair of metal plates.

"In our system, one metal plate in the capacitor is replaced by a 50 nanometer thick membrane (a nanometer is a millionth of a millimeter). It is this nanomembrane that allows us to make ultrasensitive measurements without cooling the system, explains Research Assistant Professor Albert Schliesser, who has coordinated the the experiments in Quantop's optomechanical laboratory at the Niels Bohr Institute.

He explains that the capacitor is made up of three layers. At the bottom is a chip made of glass with a layer of aluminum, where the positive and negative poles are. The nanomembrane itself is made of silicon nitrate and is coated with a thin layer of aluminum, since there has to be a metallic substance to better interact with the electric field. The chip and the membrane are only separated by a micrometer.

The radio wave signal produces fluctuations in the membrane and you can now read the signal optically using a laser beam. This is done through a complex interaction between the membrane's mechanical fluctuations, the electrical properties of the metallic layer and the light that is hitting the membrane.

The method was developed by Eugene Polzik and Albert Schliesser in collaboration with the theoretical quantum optics groups at the Niels Bohr Institute and the Joint Quantum Institute in Maryland, USA. The electromechanical chip was developed at Nanotech, DTU.

Ultrasensitive measurements

This optomechanical method has three types of noise: Electrical noise in the antenna, mechanical thermal noise in the membrane and quantum noise of the light.

The electrical noise is technical and is mostly due to disturbances from the environment.

"This has been a technical challenge and the two PhD students Tolga Bagci and Anders Simonsen have worked days and nights to solve the problem. The solution has been to find just the right way to shield the experiment," says Albert Schliesser.

Everything takes place at normal room temperature and yet there is almost no mechanical 'thermal noise'. This is surprising and is due to several factors - including the membrane's extremely high mechanical properties and that the membrane is separated from the surroundings by being enclosed in a vacuum chamber so that it responds as if it had been cooled down to two degrees Kelvin (minus 271 C).

The laser light has almost no noise, as all its photons are identical. In this way, the special properties of the nanomembrane are fully exploited.

Groundbreaking method

"This membrane is an extremely good oscillator and that is why it is so ultrasensitive. At room temperature, it works as effectively as if it was cooled down to minus 271 C and we are working to get it even closer to minus 273 degrees C, which is the absolute minimum. In addition, it is a huge advantage to use optical detection, as instead of using ordinary copper wires to transmit the signal, you can use fiber optic cables, where there is no energy loss," explains Eugene Polzik.

This is a groundbreaking new method for measuring electrical signals that could have a significant impact on future technologies. Eugene Polzik and Albert Schliesser see great potential in the new super sensitive method, both in equipment for medical treatment and for observations in space, where cosmologists measure radio radiation in order to study the infancy of the universe.

INFORMATION:

For more information contact:

Eugene Polzik, Professor, Quantop, Niels Bohr Institute, University of Copenhagen, +45 3532-5424, +45 2338-2045, polzik@nbi.dk

Albert Schliesser, Assistant Professor, Quantop, Niels Bohr Institute, University of Copenhagen, +45 3532-5401, +45 3532-5386, albert.schliesser@nbi.dk

Ultra sensitive detection of radio waves with lasers

2014-03-05

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Livestock can produce food that is better for the people and the planet

2014-03-05

With one in seven humans undernourished, and with the challenges of population growth and climate change, the need for efficient food production has never been greater. Eight strategies to cut the environmental and economic costs of keeping livestock, such as cows, goats and sheep, while boosting the quantity and quality of the food produced have been outlined by an international team of scientists.

The strategies to make ruminant - cud-chewing - livestock a more sustainable part of the food supply, led by academics at the University of Bristol's School of Veterinary ...

ALS-linked gene causes disease by changing genetic material's shape

2014-03-05

Johns Hopkins researchers say they have found one way that a recently discovered genetic mutation might cause two nasty nervous system diseases. While the affected gene may build up toxic RNA and not make enough protein, the researchers report, the root of the problem seems to be snarls of defective genetic material created at the mutation site.

The research team, led by Jiou Wang, Ph.D., an assistant professor of biochemistry and molecular biology and neuroscience at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, reports its finding March 5 on the journal Nature's ...

Study aims to define risk factors for falls in post-menopausal women

2014-03-05

ROSEMONT, Ill.–A new study appearing in the March issue of the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery (JBJS) showed that women with distal radius (wrist) fractures had decreased strength compared to similar patients without fractures. This could explain why these women were more likely to fall and might sustain future fractures.

The investigators used a variety of balance and strength tests combined with patient-provided information about walking habits to evaluate the physical performance and risk of falls for post-menopausal women with and without previous wrist fractures. ...

UF researchers find drug therapy that could eventually reverse memory decline in seniors

2014-03-05

GAINESVILLE, Fla. — It may seem normal: As we age, we misplace car keys, or can't remember a name we just learned or a meal we just ordered. But University of Florida researchers say memory trouble doesn't have to be inevitable, and they've found a drug therapy that could potentially reverse this type of memory decline.

The drug can't yet be used in humans, but the researchers are pursuing compounds that could someday help the population of aging adults who don't have Alzheimer's or other dementias but still have trouble remembering day-to-day items. Their findings will ...

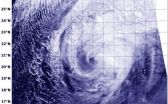

NASA sees Tropical Cyclone Faxai stretching out

2014-03-05

When a tropical cyclone becomes elongated it is a sign the storm is weakening. Imagery from NASA-NOAA's Suomi NPP satellite today revealed that wind shear was stretching out Tropical Cyclone Faxai and the storm was waning.

On March 5 at 1500 UTC/10 a.m. EST, Tropical Cyclone Faxai's center was located near 22.5 south and 155.2 east, about 699 nautical miles/804.4 miles/ 1,295 km west-northwest of Wake Island. According to the Joint Typhoon Warning Center or JTWC, Faxai's maximum sustained surface winds dropped to 50 knots/57.5 mph/92.6 kph. Faxai was moving to the northeast ...

UCSB study explores cocaine and the pleasure principle

2014-03-05

(Santa Barbara, Calif.) — On the other side of the cocaine high is the cocaine crash, and understanding how one follows the other can provide insight into the physiological effects of drug abuse. For decades, brain research has focused on the pleasurable effects of cocaine largely by studying the dopamine pathway. But this approach has left many questions unanswered.

So the Behavioral Pharmacology Laboratory (BPL) at UC Santa Barbara decided to take a different approach by examining the motivational systems that induce an animal to seek cocaine in the first place. Their ...

First-ever 3D image created of the structure beneath Sierra Negra volcano

2014-03-05

The Galápagos Islands are home to some of the most active volcanoes in the world, with more than 50 eruptions in the last 200 years. Yet until recently, scientists knew far more about the history of finches, tortoises, and iguanas than of the volcanoes on which these unusual fauna had evolved.

Now research out of the University of Rochester is providing a better picture of the subterranean plumbing system that feeds the Galápagos volcanoes, as well as a major difference with another Pacific Island chain—the Hawaiian Islands. The findings have been published in the Journal ...

Brain circuits multitask to detect, discriminate the outside world

2014-03-05

Imagine driving on a dark road. In the distance you see a single light. As the light approaches it splits into two headlights. That's a car, not a motorcycle, your brain tells you.

A new study found that neural circuits in the brain rapidly multitask between detecting and discriminating sensory input, such as headlights in the distance. That's different from how electronic circuits work, where one circuit performs a very specific task. The brain, the study found, is wired in way that allows a single pathway to perform multiple tasks.

"We showed that circuits in the ...

Similarity breeds proximity in memory, NYU researchers find

2014-03-05

Researchers at New York University have identified the nature of brain activity that allows us to bridge time in our memories. Their findings, which appear in the latest issue of the journal Neuron, offer new insights into the temporal nature of how we store our recollections and may offer a pathway for addressing memory-related afflictions.

"Our memories are known to be 'altered' versions of reality, and how time is altered has not been well understood," said Lila Davachi, an associate professor in NYU's Department of Psychology and Center for Neural Science and the ...

Are bilingual kids more open-minded?

2014-03-05

This news release is available in French. Montreal, March 5, 2014 — There are clear benefits to raising a bilingual child. But could there be some things learning a second language doesn't produce, such as a more open-minded youngster?

New research from Concordia University shows that, like monolingual children, bilingual children prefer to interact with those who speak their mother tongue with a native accent rather than with peers with a foreign accent.

The study, published in the journal Frontiers in Psychology and co-authored by psychology professors Krista ...