(Press-News.org) SALT LAKE CITY, March 12, 2014 – University of Utah chemists discovered how vibrations in chemical bonds can be used to predict chemical reactions and thus design better catalysts to speed reactions that make medicines, industrial products and new materials.

"The vibrations alone are not adequate, but combined with other classical techniques in physical organic chemistry, we are able to predict how reactions can occur," says chemistry professor Matt Sigman, senior author of the study in the Thursday, March 13, issue of the journal Nature.

"This should be applicable in a broad range of reactions. It streamlines the process of designing molecules for uses in new drugs, industrial chemicals and new materials."

Catalysts are chemicals that speed reactions between other chemicals without changing the catalyst itself.

Postdoctoral researcher Anat Milo, the study's first author, says use of the new method "can assist the design of reactions with fewer byproducts and much less waste, and the reactions would be more efficient. We are able to directly form the product we want."

She and Sigman conducted the study with Elizabeth Bess, a University of Utah Ph.D. student in chemistry. The research was funded by the National Science Foundation.

Shining Infrared Light on Bond Vibrations

Chemical bonds tie atoms together within molecules. But the bonds are not static. They vibrate. Those vibrations reflect changes in distance between atoms in the molecule. For example, in water (H2O) the sole oxygen atom is bound to two hydrogen atoms, and the two bonds constantly change in length.

"You can think of it like a spring," Sigman says. "You put two different weights on the end of a spring, and the spring vibrates once you put energy into it" by pushing or pulling. In chemical reactions, the energy is added with heat, light or electricity.

We cannot see these vibrations with our eyes, but this bending and stretching of chemical bonds can be seen if infrared light is bounced off the molecules – a method called infrared spectroscopy.

"This method is an extension of our eyes: wavelengths our eyes cannot detect, we use an instrument to detect," Milo says.

An infrared laser is aimed at a sample of a chemical – gas, liquid or solid – and certain wavelengths are absorbed. The wavelengths of the absorbed light reveal how the target molecule's chemical bonds vibrate, which in turn tells about the types and positions of atoms in the molecule, the kinds and strength of bonds among atoms and the symmetry of the molecule, Milo says.

"It's an important structure identification technique to identify the kinds of bonds in a molecule," Sigman says.

Infrared spectroscopy is a well-established method with decades of predictable results. So it now can be simulated in computers and produce results that reflect real experiments. Sigman, Milo and Bess performed such simulations in their study using the university's Center for High Performance Computing.

"We took several molecules with known bond vibrations, and we used the relationship of these molecules to each other to build a model mathematically of the relative relationship between the bond vibrations in different molecules," Sigman says. "We then built a mathematical relationship between these molecules that provides us with the ability to predict how other molecules will react based on their particular vibrations."

To show the method worked, the researchers performed three case studies, each a scenario with a different class of chemicals reacting with each other. They used computer simulations to predict the outcome of the reactions, and then experimentally verified them with real chemical reactions in the laboratory.

One case study involved how chemicals known as bisphenols reacted with acetic anhydride. A small protein known as a peptide served as a catalyst to speed the reactions.

The chemists simulated bond vibrations on different bisphenols to predict whether, when reacted with acetic anhydride and the catalyst, the resulting molecule would be "left-handed" or "right-handed" – a chemical property called chirality.

Chirality is important because when we consume a food or medicine, it must have the correct "handedness" or chirality "to essentially handshake with the molecules in your body" and do what it is supposed to do, Milo says. For example, a right-handed drug molecule may work, while the left-handed version of the same medicine may not.

"We managed to predict the handedness of the molecules accurately" 95 percent of the time by analyzing bond vibrations, Milo adds.

The second case study was similar to the first, but involved predicting the "handedness" of chemicals made when a catalyst was used to convert a double carbon-carbon bond to a single carbon-carbon bond in a chemical named diarylalkene.

In the third case study, the chemists used the method to predict whether a catalyst reacts with one side or the other side of a double carbon-carbon bond – two carbon atoms connected by two bonds instead of one – in what is called a Heck reaction, which is commonly used to make pharmaceuticals.

"It works like a champ," Sigman says.

Real-World Reactions

How can the new method be used for practical purposes?

"You would compute infrared vibrations for a specific class of molecules that you are interested in reacting," Sigman says. "You then take a handful of those molecules and you run the reaction and get the results."

"Then you take the infrared vibrations you think are important and determine the relationship between those vibrations and the reaction results," he adds. "The resulting mathematical equation allows you to make new predictions about how other chemicals in the class will react."

Sigman is collaborating with a major pharmaceutical company to use the new technique to improve chemical reactions for drug manufacturing.

"Let's say you want to synthesize a molecule," he says. "You have various methods to try, but you don't know which one will work. Our approach allows you to predict if the particular set of reagents – chemicals reacting with each other – will give the desired results."

Milo added that the new technique "is able to provide predictions that are not possible with classical chemistry methods."

For example, it allows chemists to simultaneously examine "steric" and electronic effects in reactions – something Sigman says now must be done separately. Steric effects are how the size and shape of atoms in a molecule affect how a chemical reaction works. Electronic effects involve how electrons in the atoms are shared within the molecule.

Sigman says it is important that the new method can look at both kinds of effects at once "because most modern reactions involve both properties."

INFORMATION:

Videos of bond vibrations may be downloaded from:

https://vimeo.com/album/2764811

Before the embargo expires, the case-sensitive password is BenzoicVibe

Caption for videos:

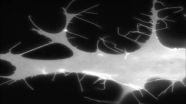

Two videos show two kinds of bond vibrations in a molecule of benzoic acid.

The first video shows how a double chemical bond between a carbon atom (gray) and oxygen atom (red) is stretched after the molecule has absorbed energy in the form of infrared light (upper right).

The second video shows the bending of single bonds between atoms of carbon (gray), oxygen (red) and hydrogen (white) (bottom right).

University of Utah chemists have discovered how such vibrations in chemical bonds can be used to predict chemical reactions and thus design better catalysts to aid reactions that make medicines, industrial products and new materials.

Credit: Anat Milo, University of Utah.

University of Utah Communications

75 Fort Douglas Boulevard, Salt Lake City, UT 84113

801-581-6773 fax: 801-585-3350

http://www.unews.utah.edu

Good vibes for catalytic chemistry

A way to make better catalysts for meds, industry and materials

2014-03-12

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

IRX3 is likely the 'fat gene'

2014-03-12

Mutations within the gene FTO have been implicated as the strongest genetic determinant of obesity risk in humans, but the mechanism behind this link remained unknown. Now, an international team of scientists has discovered that the obesity-associated elements within FTO interact with IRX3, a distant gene on the genome that appears to be the functional obesity gene. The FTO gene itself appears to have only a peripheral effect on obesity. The study appears online March 12 in Nature.

"Our data strongly suggest that IRX3 controls body mass and regulates body composition," ...

Building new drugs just got easier

2014-03-12

LA JOLLA, CA—March 12, 2014—Scientists at The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) have developed a method for modifying organic molecules that significantly expands the possibilities for developing new pharmaceuticals and improving old ones.

"This is a technology that can be applied directly to many medicinally relevant compounds," said Jin-Quan Yu, a professor in TSRI's Department of Chemistry and the senior author of the new report, which appears in Nature March 13, 2014.

The innovation makes it easier to modify existing organic compounds by attaching biologically active ...

Water-rich gem points to vast 'oceans' beneath the Earth: UAlberta study

2014-03-12

A University of Alberta diamond scientist has found the first terrestrial sample of a water-rich gem that yields new evidence about the existence of large volumes of water deep beneath the Earth.

An international team of scientists led by Graham Pearson, Canada Excellence Research Chair in Arctic Resources at the U of A, has discovered the first-ever sample of a mineral called ringwoodite. Analysis of the mineral shows it contains a significant amount of water—1.5 per cent of its weight—a finding that confirms scientific theories about vast volumes of water trapped 410 ...

Quantum chaos in ultracold gas discovered

2014-03-12

The team of Francesca Ferlaino, Institute for Experimental Physics of the University of Innsbruck, Austria, has experimentally shown chaotic behavior of particles in a quantum gas. "For the first time we have been able to observe quantum chaos in the scattering behavior of ultracold atoms," says an excited Ferlaino. The physicists used random matrix theory to confirm their results, thus asserting the universal character of this statistical theory. Nobel laureate Eugene Wigner formulated random matrix theory to describe complex systems in the 1950s. Although interactions ...

Key heart-failure culprit discovered

2014-03-12

SAN DIEGO, Calif., March 12, 2014 - A team of cardiovascular researchers from Sanford-Burnham Medical Research Institute (Sanford-Burnham), the Cardiovascular Research Center at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, and the University of California, San Diego have identified a small but powerful new player in the onset and progression of heart failure. Their findings, published in the journal Nature on March 12, also show how they successfully blocked the newly discovered culprit to halt the debilitating and chronic life-threatening condition in its tracks.

In the ...

Protein key to cell motility has implications for stopping cancer metastasis

2014-03-12

VIDEO:

Aberrant filopodia are induced by co-expression of fluorescently labeled Cdc42 and non-fluorescent IRSp53. Fluorescence shows the cell shape, because Cdc42 localizes to the plasma membrane.

Click here for more information.

PHILADELPHIA - "Cell movement is the basic recipe of life, and all cells have the capacity to move," says Roberto Dominguez, PhD, professor of Physiology at the Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania. Motility – albeit on a cellular spatial ...

Countering the caregiver placebo effect

2014-03-12

How do you know that your pet is benefiting from its pain medication? A new clinical trial design from North Carolina State University researchers could help overcome pet owners' unconscious observation bias and determine whether the drugs they test are effective.

When animals are recruited for clinical trials, particularly for pain medications, researchers must rely on owner observation to determine whether the medication is working. Sounds simple enough, but as it turns out, human and animal behavior can affect the results.

All clinical trials have a "control" ...

'Ultracold' molecules promising for quantum computing, simulation

2014-03-12

WEST LAFAYETTE, Ind. – Researchers have created a new type of "ultracold" molecule, using lasers to cool atoms nearly to absolute zero and then gluing them together, a technology that might be applied to quantum computing, precise sensors and advanced simulations.

"It sounds counterintuitive, but you can use lasers to take away the kinetic energy, resulting in radical cooling," said Yong P. Chen, an associate professor of physics and electrical and computer engineering at Purdue University.

Physicists are using lasers to achieve such extreme cooling, reducing the temperature ...

Turing's theory of morphogenesis validated 60 years after his death

2014-03-12

PITTSBURGH—British mathematician Alan Turing's accomplishments in computer science are well known—he's the man who cracked the German Enigma code, expediting the Allies' victory in World War II. He also had a tremendous impact on biology and chemistry. In his only paper in biology, Turing proposed a theory of morphogenesis, or how identical copies of a single cell differentiate, for example, into an organism with arms and legs, a head and tail.

Now, 60 years after Turing's death, researchers from the University of Pittsburgh and Brandeis University have provided the ...

Large study identifies the exact gut bacteria involved in Crohn's disease

2014-03-12

While the causes of Crohn's disease are not well understood, recent research indicates an important role for an abnormal immune response to the microbes that live in the gut. In the largest study of its kind, researchers have now identified specific bacteria that are abnormally increased or decreased when Crohn's disease develops. The findings, which appear in the March 12 issue of the Cell Press journal Cell Host & Microbe, suggest which microbial metabolites could be targeted to treat patients with this chronic and currently incurable inflammatory bowel disease.

Twenty-eight ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Urine tests confirm alcohol consumption in wild African chimpanzees

Barshop Institute to receive up to $38 million from ARPA-H, anchoring UT San Antonio as a national leader in aging and healthy longevity science

Anion-cation synergistic additives solve the "performance triangle" problem in zinc-iodine batteries

Ancient diets reveal surprising survival strategies in prehistoric Poland

Pre-pregnancy parental overweight/obesity linked to next generation’s heightened fatty liver disease risk

Obstructive sleep apnoea may cost UK + US economies billions in lost productivity

Guidelines set new playbook for pediatric clinical trial reporting

Adolescent cannabis use may follow the same pattern as alcohol use

Lifespan-extending treatments increase variation in age at time of death

From ancient myths to ‘Indo-manga’: Artists in the Global South are reframing the comic

Putting some ‘muscle’ into material design

House fires release harmful compounds into the air

Novel structural insights into Phytophthora effectors challenge long-held assumptions in plant pathology

Q&A: Researchers discuss potential solutions for the feedback loop affecting scientific publishing

A new ecological model highlights how fluctuating environments push microbes to work together

Chapman University researcher warns of structural risks at Grand Renaissance Dam putting property and lives in danger

Courtship is complicated, even in fruit flies

Columbia announces ARPA-H contract to advance science of healthy aging

New NYUAD study reveals hidden stress facing coral reef fish in the Arabian Gulf

36 months later: Distance learning in the wake of COVID-19

Blaming beavers for flood damage is bad policy and bad science, Concordia research shows

The new ‘forever’ contaminant? SFU study raises alarm on marine fiberglass pollution

Shorter early-life telomere length as a predictor of survival

Why do female caribou have antlers?

How studying yeast in the gut could lead to new, better drugs

Chemists thought phosphorus had shown all its cards. It surprised them with a new move

A feedback loop of rising submissions and overburdened peer reviewers threatens the peer review system of the scientific literature

Rediscovered music may never sound the same twice, according to new Surrey study

Ochsner Baton Rouge expands specialty physicians and providers at area clinics and O’Neal hospital

New strategies aim at HIV’s last strongholds

[Press-News.org] Good vibes for catalytic chemistryA way to make better catalysts for meds, industry and materials