(Press-News.org) The body clock's natural rhythm could be utilized to improve current therapies to delay the onset of chronic lung diseases.

Scientists at The University of Manchester have discovered a rhythmic defence pathway in the lung controlled by our body clocks, which is essential to combat daily exposure to toxins and pollutants.

Internal biological timers (circadian clocks) are found in almost all living things driving diverse processes such as sleep/wake cycles in humans to leaf movement in plants. In mammals including humans, circadian clocks are found in most cells and tissues of the body, and orchestrate daily rhythms in our physiology.

The research team's ground breaking findings, which are being published in Genes & Development, have for the first time found that the circadian clock in the mouse lung rhythmically switches on and off genes controlling the antioxidant defense pathway. This 24 hourly rhythm enables the lungs to anticipate and withstand daily exposure to pollutants.

The research was led by Dr Qing-Jun Meng from The University of Manchester who is also a Medical Research Council (MRC) Research Fellow. He has been studying body clocks for a number of years and has been awarded an MRC Career Development Award to establish the relationship between the disruption of circadian rhythms and the susceptibility to human diseases, especially those associated with old age.

Dr Meng said: "We used a mouse model that mimics human pulmonary fibrosis, and found that an oxidative and fibrotic challenge delivered to the lungs during the night phase (when mice are active) causes more severe lung damages than the same challenge administered during the day which is a mouse's resting phase."

This means that the rhythm of this lung clock gives an indication of more suitable times of the day for drugs to be administered to patients suffering from oxidative/fibrotic diseases such as pulmonary fibrosis, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Dr Meng continued: "Our findings show that timed administration of the antioxidant compound sulforaphane, effectively attenuates the severity of the lung fibrosis in this mouse model."

In other words the research suggests that taking drug treatments for oxidative and fibrotic diseases according to the lung clock time could increase their effectiveness, which would allow a lower dosage and consequently reduce side effects.

Dr Vanja Pekovic-Vaughan, who was part of the University's research team, said: "This research is the first to show that a functioning clock in the lung is essential to maintain the protective tissue function against oxidative stress and fibrotic challenges. We envisage a scenario whereby chronic rhythm disruption (e.g., during ageing or shift work) may compromise the temporal coordination of the antioxidant pathway, contributing to human disease."

This latest study is part of on-going research that is exploring how chronic disruption to body clocks by changes like ageing or shift work contribute to a number of conditions such as osteoarthritis, cardiovascular disease, breast cancer, and mood disorder.

Dr Meng said: "Our next step is to test our theory that similar rhythmic activity of the antioxidant defence pathway also operates in human lungs. This will enable us to translate our findings and identify the proper clock time to treat chronic lung diseases that are known to involve oxidative stress.

"Funded by an MRC Fellowship Partnership Award, we have teamed up with GlaxoSmithKline to explore the potential of utilizing the body clock mechanisms to improve the efficiency of the current antioxidant compounds for diseases. Timing the delivery of drugs - so-called 'chrono-therapy' or 'chrono-pharmacology' - has already demonstrated clinical benefits in treatment of cancer and arthritis," he said.

Professor Stuart Farrow, a Director in the Respiratory therapy area at GSK (who is also the industrial partner for Dr Meng on the MRC Fellowship Partnership Award), commented: "Chronic lung diseases are prevalent and debilitating, and continue to be an important area of unmet medical need. This exciting new research reveals an opportunity to harness the body clock to provide valuable benefit to patients."

INFORMATION:

Notes for editors

Kath Paddison

Media Relations Officer

Faculty of Life Sciences

The University of Manchester

Tel. +44 (0)161 275 2111

Email: kath.paddison@manchester.ac.uk

Please contact us for a copy of the paper 'The circadian clock regulates rhythmic

activation of the NRF2/glutathionemediated antioxidant defense pathway to modulate pulmonary fibrosis' by Vanja Pekovic-Vaughan, Julie Gibbs, Hikari Yoshitane, Nan Yang, Dharshika Pathiranage, Baoqiang Guo, Aya Sagami, Keiko Taguchi, David Bechtold, Andrew Loudon, Masayuki Yamamoto, Jefferson Chan, Gijsbertus T.J. van der Horst, Yoshitaka Fukada, Qing-Jun Meng

New research links body clocks to chronic lung diseases

2014-03-18

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Earthquakes caused by clogged magma a warning sign of eruption, study shows

2014-03-18

New research in Geophysical Research Letters examines earthquake swarms caused by mounting volcanic pressure which may signal an imminent eruption. The research team studied Augustine Volcano in Alaska which erupted in 2006 and found that precursory earthquakes were caused by a block in the lava flow.

36 hours before the first magmatic explosions, a swarm of 54 earthquakes was detected across the 13-station seismic network on Augustine Island. By analyzing the resulting seismic waves, the authors found that the earthquakes were being triggered from sources within the ...

Eat more, die young: Why eating a diet very low in nutrients can extend lifespan

2014-03-18

A new evolutionary theory in BioEssays claims that consuming a diet very low in nutrients can extend lifespan in laboratory animals, a finding which could hold clues to promoting healthier ageing in humans.

Scientists have known for decades that severely restricted food intake reduces the incidence of diseases of old age, such as cancer, and increases lifespan.

"This effect has been demonstrated in laboratories around the world, in species ranging from yeast to flies to mice. There is also some evidence that it occurs in primates," says lead author, Dr Margo Adler, ...

Follow the ant trail for drug design

2014-03-18

This news release is available in German. The path to developing new drugs is a long one. If a target is identified for a new active agent – for instance a particular protein that plays a key role in a disease – an active molecule that binds to the target must then be developed. Pharmaceutical companies trawl through their collections of chemicals for substances that act on the target protein in the desired fashion. However, these compounds are often just the starting point for a long process of adjustment and testing. Chemists use computer simulations to design new ...

Democrats, Republicans see each other as mindless -- unless they pose a threat

2014-03-18

We are less likely to humanize members of groups we don't belong to—except, under some circumstances, when it comes to members of the opposite political party. A study by researchers at New York University and Harvard Business School suggests that we are more prone to view members of the opposite political party as human if we view those individuals as threatening.

"It's hardly surprising that we dehumanize those who are not part of our groups," says Jay Van Bavel, an assistant professor in NYU's Department of Psychology and one of the study's co-authors. "However, what ...

Research on the protein gp41 could help towards designing future vaccinations against HIV

2014-03-18

This news release is available in Spanish. Researchers from the University of Granada have discovered, for the first time, an allosteric interaction (that is, a regulation mechanism whereby enzymes can be activated or de-activated) between this protein, which forms part of the sheath of the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) and the antibody 2F5 (FAB), a potent virus neutralizer. This important scientific breakthrough could help specialists to understand the mechanisms behind generating immune responses and help towards the design of future vaccines against the HIV ...

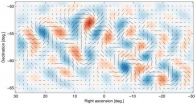

First direct evidence of cosmic inflation

2014-03-18

Almost 14 billion years ago, the universe we inhabit burst into existence in an extraordinary event that initiated the Big Bang. In the first fleeting fraction of a second, the universe expanded exponentially, stretching far beyond the view of our best telescopes. All this, of course, was just theory.

Researchers from the BICEP2 collaboration today announced the first direct evidence for this cosmic inflation. Their data also represent the first images of gravitational waves, or ripples in space-time. These waves have been described as the "first tremors of the Big Bang." ...

Immunologists present improved mass spectrometric method for proteomic analyses

2014-03-18

When it comes to analyzing cell components or body fluids or developing new medications, there is no way around mass spectrometry. Mass spectrometry is a highly sensitive method of measurement that has been used for many years for the analysis of chemical and biological materials. Scientists at the Institute of Immunology of the University Medical Center of Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz (JGU) have now significantly improved this analytical method that is widely employed within their field. They have also developed a software program for the integrated analysis of ...

UNH research: Positive memories of exercise spur future workouts

2014-03-18

DURHAM, N.H. – Getting motivated to exercise can be a challenge, but new research from the University of New Hampshire shows that simply remembering a positive memory about exercise may be just what it takes to get on the treadmill. This is the first study to explore how positive memories can influence future workouts.

"This study underscores the power of memory's directive influence in a new domain with practical applications: exercise behaviors. These results provide the first experimental evidence that autobiographical memory activation can be an effective tool in ...

Male, stressed, and poorly social

2014-03-18

Stress, this enemy that haunts us every day, could be undermining not only our health but also our relationships with other people, especially if we are men. In fact, stressed women apparently become more "prosocial". These are the main findings of a study carried out with the collaboration of Giorgia Silani, from the International School for Advanced Studies (SISSA) of Trieste. The study was coordinated by the Social Cognitive Neuroscience Unit of the University of Vienna and saw the participation of the University of Freiburg.

"There's a subtle boundary between the ...

What's so bad about feeling happy?

2014-03-18

Why is being happy, positive and satisfied with life the ultimate goal of so many people, while others steer clear of such feelings? It is often because of the lingering belief that happiness causes bad things to happen, says Mohsen Joshanloo and Dan Weijers of the Victoria University of Wellington in New Zealand. Their article, published in Springer's Journal of Happiness Studies, is the first to review the concept of aversion to happiness, and looks at why various cultures react differently to feelings of well-being and satisfaction.

"One of these cultural phenomena ...