(Press-News.org) CAMBRIDGE, Mass. (March 16, 2014) – For several years, a class of anti-diabetic drugs known as biguanides, has been associated with anti-cancer properties. A number of retrospective studies have shown that the widely used diabetes drug metformin can benefit some cancer patients. Despite this intriguing correlation, it has been unclear how metformin might exert its anti-cancer effects and, perhaps more importantly, in which patients.

Now, Whitehead Institute scientists are beginning to unravel this mystery, identifying a major mitochondrial pathway that imbues cancer cells with the ability to survive in low-glucose environments. By finding cancer cells with defects in this pathway or with impaired glucose utilization, the scientists can predict which tumor will be sensitive to the anti-diabetic drugs known to inhibit the pathway in question. Their work is described online this week in the journal Nature.

To study how cancer cells survive in the kind of low-glucose environment found within cancerous tumors, Kıvanç Birsoy and Richard Possemato, postdoctoral researchers in Whitehead Member David Sabatini's lab, developed a system that circulates low-nutrient media continuously around cells. Of the 30 cancer cell lines tested within this system, most appeared unaffected by a lack of glucose. However, a few of the lines thrived and reproduced rapidly, while others struggled. The varied responses to a glucose shortage were puzzling.

"No one really understood why cancer cells had these responses or whether they were important for the formation of the tumor," says Possemato, who coauthored the Nature paper with Birsoy. "The cancer-relevance of the alterations that we found as underlying this response to low glucose will still need to be investigated."

Birsoy and Possemato wondered whether certain cancer cells' susceptibility to a low glucose environment could be exploited to attack tumors. They screened overly distressed cells for genes whose suppression improved or further hindered the cells' survival rates. The screen flagged genes involved in glucose transportation and oxidative phosphorylation, a metabolic pathway in mitochondria. The powerhouses of a cell, mitochondria are membrane-bound organelles with their own DNA, including genes that control oxidative phosphorylation.

Birsoy and Possemato hypothesized that cancer cells with mutations in these genes are over-taxing their mitochondria under normal conditions. When placed in a harsh, low-glucose environment, the mitochondria are maxed out, and the cells suffer. If true, the hypothesis would suggest that further impairing mitochondrial function, with biguanides—which are known oxidative phosphorylation inhibitors—could push the mitochondria beyond their limits, to the detriment of the cancer cells.

They first tested their hypothesis in vitro on 13 cell lines with glucose utilization defects and mitochondrial DNA mutations. Compared to control cells, those sensitive to low glucose were five to 20 times more susceptible to phenformin, a more potent biguanide than metformin. Birsoy and Possemato then tested phenformin's effectiveness in mice implanted with tumors derived from low-glucose-sensitive cancer cells. The drug inhibited the tumors' growth.

"These results show that mitochondrial DNA mutations and glucose import defects can be used as biomarkers for biguanide sensitivity to determine if a cancer patient might benefit from these drugs," says Birsoy. "And this is the first time that anyone has shown that the direct cytotoxic effects of this class of drugs, including metformin and phenformin, on cancer cells are mediated through their effect on mitochondria."

To confirm the accuracy of their proposed biomarkers, Birsoy and Possemato want to analyze previous clinical trials to see if cancer patients with the proposed biomarkers fared better with metformin treatment than patients without the biomarkers.

INFORMATION:

This work is supported by the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society, Jane Coffin Childs Fund, Council of Higher Education Turkey, Karadeniz T. University Scholarships, David H. Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research at MIT, Alexander and Margaret Stewart Trust Fund, and the National Institutes of Health (NIH grants K99 CA168940 and CA103866, CA129105, and AI07389).

Written by Nicole Giese Rura

David Sabatini's primary affiliation is with Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research, where his laboratory is located and all his research is conducted. He is also a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator and a professor of biology at Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Full Citation:

"Metabolic determinants of cancer cell sensitivity to glucose limitation and biguanides"

Nature, March 16, 2014.

Kıvanç Birsoy (1,2,3,4,*), Richard Possemato (1,2,3,4,*), Franziska K. Lorbeer (1), Erol C. Bayraktar (1), Prathapan Thiru (1), Burcu Yucel (1), Tim Wang (1,2,3,4), Walter W. Chen (1,2,3,4), Clary B. Clish (3) and David M. Sabatini (1,2,3,4).

1. Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research, Nine Cambridge Center, Cambridge, MA 02142, USA

2. Howard Hughes Medical Institute and Department of Biology, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA 02139, USA

3. Broad Institute of Harvard and MIT, Seven Cambridge Center, Cambridge, MA 02142, USA

4. The David H. Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research at MIT, 77 Massachusetts Avenue, Cambridge, MA 02139, USA

*These authors contributed equally to this work

How diabetes drugs may work against cancer

2014-03-18

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Less is more: New theory on why very low nutrient diets can extend lifespan

2014-03-18

UNSW scientists have developed a new evolutionary theory on why consuming a diet that is very low in nutrients extends lifespan in laboratory animals - research that could hold clues to promoting healthier ageing in humans.

Scientists have known for decades that severely restricted food intake reduces the incidence of diseases of old age, such as cancer, and increases lifespan.

"This effect has been demonstrated in laboratories around the world, in species ranging from yeast to flies to mice. There is also some evidence that it occurs in primates," says lead author, Dr ...

Electronic media associated with poorer well-being in children

2014-03-18

Bottom Line: The use of electronic media, such as watching television, using computers and playing electronic games, was associated with poorer well-being in children.

Author: Trina Hinkley, Ph.D., of Deakin University, Melbourne, Australia, and colleagues.

Background: Using electronic media can be a sedentary behavior and sedentary behavior is associated with adverse health outcomes and may be detrimental at a very young age.

How the Study Was Conducted: The authors used data from the European Identification and Prevention of Dietary- and Lifestyle-Induced Health ...

COPD associated with increased risk for mild cognitive impairment

2014-03-18

Bottom Line: A diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in older adults was associated with increased risk for mild cognitive impairment (MCI), especially MCI of skills other than memory, and the greatest risk was among patients who had COPD for more than five years.

Author: Balwinder Singh, M.D., M.S., of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., and colleagues.

Background: COPD is an irreversible limitation of airflow into the lungs, usually caused by smoking. More than 13.5 million adults 25 years or older in the U.S. have COPD. Previous research has suggested ...

Global problem of fisheries bycatch needs global solutions

2014-03-18

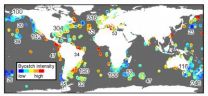

SAN DIEGO, Calif. (March 17, 2014)—Whenever fishing vessels harvest fish, other animals can be accidentally caught or entangled in fishing gear as bycatch. Numerous strategies exist to prevent bycatch, but data have been lacking on the global scale of this issue. A new in-depth analysis of global bycatch data provides fisheries and the conservation community with the best information yet to help mitigate the ecological damage of bycatch and helps identify where mitigation measures are most needed.

"When we talk about fisheries' catch, we're talking about what fishers are ...

New hope for early detection of stomach cancer

2014-03-18

University of Adelaide research has provided new hope for the early detection of stomach cancer with the identification of four new biomarkers in the blood of human cancer patients.

Stomach or gastric cancer is the fourth most common cancer in the world and the second leading cause of death due to cancer.

"Stomach cancer is typically without symptoms in the early stages so most cancers are not diagnosed until the later stages, and the survival rates are therefore low," says Associate Professor Peter Hoffmann, project leader and Director of the University's Adelaide ...

Chicken bones tell true story of Pacific migration

2014-03-18

Did the Polynesians beat Columbus to South America? Not according to the tale of migration uncovered by analysis of ancient DNA from chicken bones recovered in archaeological digs across the Pacific.

The ancient DNA has been used to study the origins and dispersal of ancestral Polynesian chickens, reconstructing the early migrations of people and the animals they carried with them.

The study, led by the University of Adelaide's Australian Centre for Ancient DNA (ACAD) and published today in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, reveals that previous claims ...

Hubble revisits the Monkey Head Nebula for 24th birthday snap

2014-03-18

To celebrate its 24th year in orbit, the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope has released a beautiful new image of part of NGC 2174, also known as the Monkey Head Nebula. This colourful region is filled with young stars embedded within bright wisps of cosmic gas and dust.

NGC 2174 lies about 6400 light-years away in the constellation of Orion (The Hunter). Hubble previously viewed this part of the sky back in 2001, creating a stunning image released in 2011, and the space telescope has now revisited the region to celebrate its 24th year of operation.

Nebulae are a favourite ...

Crop intensification and organic fertilizers can be a long-term solution to perennial food shortages in Africa

2014-03-18

Farmers in Africa can increase their food production if they avoid over dependence on chemical fertilizers, pesticides and practice agricultural intensification - growing more food on the same amount of land – using natural and resource-conserving approaches such as agroforestry.

According to scientists at the World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF), crop production in Africa is seriously hampered by the degradation of soil fertility, water and biodiversity resources. Currently, yields for important cereals such as maize have stagnated at 1 tone per hectare. Climate change ...

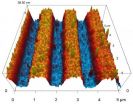

Researchers change coercivity of material by patterning surface

2014-03-18

Researchers from North Carolina State University have found a way to reduce the coercivity of nickel ferrite (NFO) thin films by as much as 80 percent by patterning the surface of the material, opening the door to more energy efficient high-frequency electronics, such as sensors, microwave devices and antennas.

"This technique reduces coercivity, which will allow devices to operate more efficiently, reducing energy use and improving device performance," says Goran Rasic, a Ph.D. student at NC State and lead author of a paper describing the work. "We did this work on NFO ...

New research links body clocks to chronic lung diseases

2014-03-18

The body clock's natural rhythm could be utilized to improve current therapies to delay the onset of chronic lung diseases.

Scientists at The University of Manchester have discovered a rhythmic defence pathway in the lung controlled by our body clocks, which is essential to combat daily exposure to toxins and pollutants.

Internal biological timers (circadian clocks) are found in almost all living things driving diverse processes such as sleep/wake cycles in humans to leaf movement in plants. In mammals including humans, circadian clocks are found in most cells and ...