(Press-News.org) VIDEO:

Ben-Shahar describes research with fruit flies that shows messenger RNA plays an active as well as a passive role in the cell. In addition to encoding for a protein, it...

Click here for more information.

Our genome, we are taught, operates by sending instructions for the manufacture of proteins from DNA in the nucleus of the cell to the protein-synthesizing machinery in the cytoplasm. These instructions are conveyed by a type of molecule called messenger RNA (mRNA).

Francis Crick , co-discoverer of the structure of the DNA molecule, called the one-way flow of information from DNA to mRNA to protein the "central dogma of molecular biology."

Yehuda Ben-Shahar and his team at Washington University in St. Louis have discovered that some mRNAs have a side job unrelated to making the protein they encode. They act as regulatory molecules as well, preventing other genes from making protein by marking their mRNA molecules for destruction.

"Our findings show that mRNAS, which are typically thought to act solely as the template for protein translation, can also serve as regulatory RNAs, independent of their protein-coding capacity," Ben-Shahar said. "They're not just messengers but also actors in their own right." The finding was published in the March 18 issue of the new open-access journal eLife.

Although Ben-Shahar's team, which included neuroscience graduate student Xingguo Zheng and collaborators Aaron DiAntonio and his graduate student Vera Valakh, was studying heat stress in fruit flies when they made this discovery, he suspects this regulatory mechanism is more general than that.

Many other mRNAs, including ones important to human health, will be found to be regulating the levels of proteins other than the ones they encode. Understanding mRNA regulation may provide new purchase on health problems that haven't yielded to approaches based on Crick's central dogma.

Is gene expression regulated directly?

Ben-Shahar's original objective was to better understand how organisms maintain their physiological balance when they are buffeted by changes in the environment.

Neuroscientists know that if you warm neurons in culture, he said, the neurons will fire more rapidly. And if the culture is cooled down, the neurons slow down. Neurons in an organism, however, behave differently from those in a dish. Usually the organism is able to cushion its nervous system from heat stress, at least within limits. But nobody knew how they did this.

As a fruit fly scientist, Ben-Shahar was aware that there are mutations in fruit flies that make them bad at buffering heat stress, and this provided a starting point for his research.

One of these genes is actually called seizure, because flies with a broken copy of this gene are particularly sensitive to heat. Raising the temperature even 10 degrees sends them into seizures. "They seize very fast, in seconds," Ben-Shahar said.

"When we looked at seizure (sei) we noticed that there is another gene on the opposite strand of the double-stranded DNA molecule called pickpocket 29 (ppk29)," Ben-Shahar said. This was interesting because seizure codes for a protein "gate" that lets potassium ions out of the neuron and pickpocket 29 codes for a gate that lets sodium ions into the neuron.

Neurons are "excitable" cells, he said, because they tightly control the gradients of potassium and sodium across their cell membranes. Rapid changes in these gradients cause a nerve to "fire," to stop firing, and to repolarize, so that it can fire again.

The scientists soon showed that transcription of these genes is coordinated. When the flies are too hot, they make more transcripts of the sei gene and fewer of ppk29. And when the flies cooled down, the opposite happened. If the central dogma held in this case, the neurons might be buffering the effects of heat by altering the expression of these genes.

One problem with this idea, though, is that gene transcription is slow and the flies, remember, seize in seconds. Was this mechanism fast enough to keep up with sudden changes in the environment?

Does RNA interference regulate gene expression?

But the scientists had also noticed that the two genes overlapped a bit at their tips. The tips, called the 3' UTRs (untranslated regions), don't code for protein but are transcribed into mRNA.

That got them thinking. When the two genes were transcribed into mRNA, the two ends would complement one another like the hooks and loops of a Velcro fastener. Like the hooks and loops, they would want to stick together, forming a short section of double-stranded mRNA. And double-stranded mRNA, they knew, activates biochemical machinery that degrades any mRNA molecules with the same genetic sequence.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0H6EgLCYcX4&feature=youtu.be

Double-stranded RNA binds to a protein complex called Dicer that cuts it into fragments. Another protein complex, RISC, binds these fragments. One of the RNA strands is eliminated but the other remains bound to the RISC complex. RISC and its attached RNA then becomes a heat-seeking missile that finds and destroys other copies of the same RNA. If the mRNA molecules disappear, their corresponding proteins are never made.

It turned out that heat sensitivity in the fly is all about potassium channel, said Ben-Shahar. What if, he thought, the two mRNAs stuck together, the mRNA segment encoding the potassium channel was bound to RISC and other copies of the potassium channel mRNA were destroyed. This was another, potentially faster way the neurons might be controlling the excitability of their membranes.

A designer fly provides an answer

Which is it? Is regulation occurring at the gene level or the mRNA level?

To find out, the scientists made designer fruit flies that had various combinations of the genes and their sticky noncoding ends. One of these transgenic fly lines was missing the part of the gene coding for the ppk29 protein but still made lots of mRNA copies of the sticky bit at the end of ppk29. When there were lots of these isolated sticky bits, sei mRNA levels dropped. This fly was as heat sensitive as a fly completely missing the sei gene.

This combination of genotype and phenotype held the answer to the regulatory problem. First of all, mRNA from one gene (ppk29) is regulating the mRNA of another gene (sei). And, second, the regulatory part of ppk29 is the untranslated bit at the end of the mRNA. When this bit sticks to a complete transcript of the sei gene (including, of course, its sticky bit), the RISC machinery destroys any copies of the sei mRNA it finds.

So the gene that codes for a sodium channel regulates the expression of the potassium channel gene. And it does so after the genes are transcribed into mRNA; it's mRNA-dependent regulation.

The interaction between sei and ppk29 is unlikely to be unique, Ben-Shahar said. The potassium channel is highly conserved among species, and analyses of the genome sequences in flies and in people show that two of three fly genes for this type of potassium channel and three of eight human genes for these channels have overlapping 3' UTR ends, just as do sei and ppk29.

Why does this regulatory mechanism exist? Ben-Shahar hates getting out in front of his data, but he points out that transcribing DNA into mRNA is a slower process than translating mRNA into protein. So it may be, he said, that neurons maintain a pool of mRNAs in readiness, and mRNA interference is a way to quickly knock down that pool to prevent the extra mRNA from being translated into proteins that might get the organism in trouble.

INFORMATION: END

A novel mechanism for fast regulation of gene expression

Messenger RNA normally tells cellular machinery which protein to make; But sometimes it has a secret mission as well

2014-03-18

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

New lens design drastically improves kidney stone treatment

2014-03-18

DURHAM, N.C. -- Duke engineers have devised a way to improve the efficiency of lithotripsy -- the demolition of kidney stones using focused shock waves. After decades of research, all it took was cutting a groove near the perimeter of the shock wave-focusing lens and changing its curvature.

"I've spent more than 20 years investigating the physics and engineering aspects of shock wave lithotripsy," said Pei Zhong, the Anderson-Rupp Professor of Mechanical Engineering and Materials Science at Duke University. "And now, thanks to the willingness of Siemens (a leading lithotripter ...

Sea anemone is genetically half animal, half plant

2014-03-18

The team led by evolutionary and developmental biologist Ulrich Technau at the University of Vienna discovered that sea anemones display a genomic landscape with a complexity of regulatory elements similar to that of fruit flies or other animal model systems. This suggests, that this principle of gene regulation is already 600 million years old and dates back to the common ancestor of human, fly and sea anemone. On the other hand, sea anemones are more similar to plants rather to vertebrates or insects in their regulation of gene expression by short regulatory RNAs called ...

Effect of receptor activity-modifying protein-1 on vascular smooth muscle cells

2014-03-18

Bei Shi, Xianping Long, Ranzun Zhao, Zhijiang Liu, Dongmei Wang and Guanxue Xu, researchers at the First Affiliated Hospital of Zunyi Medical College within the Guizhou Province of China, have reported an approach for improving the use of stem cells for improvement of infarcted heart function and damage to the arteries in the March 2013 issue of Experimental Biology and Medicine. They have discovered that mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) transfected with a recombinant adenovirus containing the human receptor activity-modifying protein 1 (hRAMP1) gene (EGFP-hRAMP1-MSCs) when ...

Vast gene-expression map yields neurological and environmental stress insights

2014-03-18

A consortium led by scientists from the U.S. Department of Energy's Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) has conducted the largest survey yet of how information encoded in an animal genome is processed in different organs, stages of development, and environmental conditions. Their findings paint a new picture of how genes function in the nervous system and in response to environmental stress.

They report their research this week in the Advance Online Publication of the journal Nature.

The scientists studied the fruit fly, an important model organism ...

Chinese scientists report new findings on mutations identification of esophageal cancer

2014-03-18

March 16, 2014, Shenzhen, China – In a collaborative study, researchers from Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, BGI, Shantou University Medical College and other institutions identified important alterations of tumor-associated genes and tumorigenic pathways in esophageal squamous cell cancer (ESCC), one of the leading cause of cancer death worldwide. The all-round work was published online today in the international journal Nature, providing a new eye-opening insight into developing novel biomarkers for therapeutic strategies of this ...

How diabetes drugs may work against cancer

2014-03-18

CAMBRIDGE, Mass. (March 16, 2014) – For several years, a class of anti-diabetic drugs known as biguanides, has been associated with anti-cancer properties. A number of retrospective studies have shown that the widely used diabetes drug metformin can benefit some cancer patients. Despite this intriguing correlation, it has been unclear how metformin might exert its anti-cancer effects and, perhaps more importantly, in which patients.

Now, Whitehead Institute scientists are beginning to unravel this mystery, identifying a major mitochondrial pathway that imbues cancer ...

Less is more: New theory on why very low nutrient diets can extend lifespan

2014-03-18

UNSW scientists have developed a new evolutionary theory on why consuming a diet that is very low in nutrients extends lifespan in laboratory animals - research that could hold clues to promoting healthier ageing in humans.

Scientists have known for decades that severely restricted food intake reduces the incidence of diseases of old age, such as cancer, and increases lifespan.

"This effect has been demonstrated in laboratories around the world, in species ranging from yeast to flies to mice. There is also some evidence that it occurs in primates," says lead author, Dr ...

Electronic media associated with poorer well-being in children

2014-03-18

Bottom Line: The use of electronic media, such as watching television, using computers and playing electronic games, was associated with poorer well-being in children.

Author: Trina Hinkley, Ph.D., of Deakin University, Melbourne, Australia, and colleagues.

Background: Using electronic media can be a sedentary behavior and sedentary behavior is associated with adverse health outcomes and may be detrimental at a very young age.

How the Study Was Conducted: The authors used data from the European Identification and Prevention of Dietary- and Lifestyle-Induced Health ...

COPD associated with increased risk for mild cognitive impairment

2014-03-18

Bottom Line: A diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in older adults was associated with increased risk for mild cognitive impairment (MCI), especially MCI of skills other than memory, and the greatest risk was among patients who had COPD for more than five years.

Author: Balwinder Singh, M.D., M.S., of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., and colleagues.

Background: COPD is an irreversible limitation of airflow into the lungs, usually caused by smoking. More than 13.5 million adults 25 years or older in the U.S. have COPD. Previous research has suggested ...

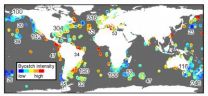

Global problem of fisheries bycatch needs global solutions

2014-03-18

SAN DIEGO, Calif. (March 17, 2014)—Whenever fishing vessels harvest fish, other animals can be accidentally caught or entangled in fishing gear as bycatch. Numerous strategies exist to prevent bycatch, but data have been lacking on the global scale of this issue. A new in-depth analysis of global bycatch data provides fisheries and the conservation community with the best information yet to help mitigate the ecological damage of bycatch and helps identify where mitigation measures are most needed.

"When we talk about fisheries' catch, we're talking about what fishers are ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Brainwaves of mothers and children synchronize when playing together – even in an acquired language

A holiday to better recovery

Cal Poly’s fifth Climate Solutions Now conference to take place Feb. 23-27

Mask-wearing during COVID-19 linked to reduced air pollution–triggered heart attack risk in Japan

Achieving cross-coupling reactions of fatty amide reduction radicals via iridium-photorelay catalysis and other strategies

Shorter may be sweeter: Study finds 15-second health ads can curb junk food cravings

Family relationships identified in Stone Age graves on Gotland

Effectiveness of exercise to ease osteoarthritis symptoms likely minimal and transient

Cost of copper must rise double to meet basic copper needs

A gel for wounds that won’t heal

Iron, carbon, and the art of toxic cleanup

Organic soil amendments work together to help sandy soils hold water longer, study finds

Hidden carbon in mangrove soils may play a larger role in climate regulation than previously thought

Weight-loss wonder pills prompt scrutiny of key ingredient

Nonprofit leader Diane Dodge to receive 2026 Penn Nursing Renfield Foundation Award for Global Women’s Health

Maternal smoking during pregnancy may be linked to higher blood pressure in children, NIH study finds

New Lund model aims to shorten the path to life-saving cell and gene therapies

Researchers create ultra-stretchable, liquid-repellent materials via laser ablation

Combining AI with OCT shows potential for detecting lipid-rich plaques in coronary arteries

SeaCast revolutionizes Mediterranean Sea forecasting with AI-powered speed and accuracy

JMIR Publications’ JMIR Bioinformatics and Biotechnology invites submissions on Bridging Data, AI, and Innovation to Transform Health

Honey bees navigate more precisely than previously thought

Air pollution may directly contribute to Alzheimer’s disease

Study finds early imaging after pediatric UTIs may do more harm than good

UC San Diego Health joins national research for maternal-fetal care

New biomarker predicts chemotherapy response in triple-negative breast cancer

Treatment algorithms featured in Brain Trauma Foundation’s update of guidelines for care of patients with penetrating traumatic brain injury

Over 40% of musicians experience tinnitus; hearing loss and hyperacusis also significantly elevated

Artificial intelligence predicts colorectal cancer risk in ulcerative colitis patients

Mayo Clinic installs first magnetic nanoparticle hyperthermia system for cancer research in the US

[Press-News.org] A novel mechanism for fast regulation of gene expressionMessenger RNA normally tells cellular machinery which protein to make; But sometimes it has a secret mission as well