(Press-News.org) The problems people with autism have with memory formation, higher-level thinking and social interactions may be partially attributable to the activity of receptors inside brain cells, researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have learned.

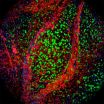

Scientists were already aware that the type of receptor in question was a potential contributor to these problems – when located on the surfaces of brain cells. Until now, though, the role of the same type of receptor located inside the cell had gone unrecognized. Such receptors inside cells significantly outnumber the same type of receptors on the surface of cells.

The receptor under study, known as the mGlu5 receptor, becomes activated when it binds to the neurotransmitter glutamate, which is associated with learning and memory. This leads to chain reactions that convert the glutamate's signal into messages traveling inside the cell.

In the new study, scientists working with cells in a dish linked mGlu5 receptors inside cells to processes that turn down the volume at which brain cells talk to each other. These volume changes, essential for learning and memory, may become exaggerated in people with autism.

Pharmaceutical companies have developed therapeutic compounds to decrease signaling associated with the mGlu5 receptor, moderating its effects on brain cells' volume knobs. But the compounds were designed to target mGlu5 surface receptors. In light of the new findings, the scientists question if those drugs will reach the receptors inside cells.

"Our results suggest that to have the greatest therapeutic benefit, we may need to make sure we're blocking all of this type of receptor, both inside and on the surface of the cell," said senior investigator Karen O'Malley, PhD, professor of neurobiology.

The findings, published March 25 in The Journal of Neuroscience, also add a significant new dimension to basic brain cell function. Scientists have long assumed that brain cell receptors are only active on the surface of cells. The new study shows that receptors can be active inside cells, and their effects can be considerably different from the same receptors located on the cell surface.

"The traditional wisdom was that receptors inside the cell were either waiting to go to work on the surface or had just finished working there," said O'Malley. "But when we compared how much of the mGlu5 receptor was on the surface of cells to how much was inside it, we were seeing so much more receptor inside the cell – at least 50 percent, and in some cases as much as 90 percent – that we wondered if the interior receptors had separate functions."

In earlier studies, O'Malley and her collaborators showed that mGlu5 receptors on the cell surface sent completely different messages than the same receptors inside the cell.

The scientists knew that most autism studies were conducted with compounds that blocked mGlu5 receptors but could not get into the cell. To determine whether blocking inside receptors would have different effects, O'Malley collaborated with Yukitoshi Izumi, MD, PhD, research professor of psychiatry, and Charles F. Zorumski, MD, the Samuel B. Guze Professor and head of the Department of Psychiatry, who study cell-based models of learning and memory.

When the scientists examined these model systems using compounds that allowed them to activate only mGlu5 receptors within cells, they found that these receptors played a bigger role in turning down the volume of brain cell communications than did the cell surface receptors.

In the last few years, scientists have found that 20 or more types of brain cell receptors located on cell surfaces also are present at high levels inside cells, O'Malley noted.

"This should be a factor we consider when we design drugs to target brain cell receptors," she said. "Do we want to reach cell surface receptors, receptors inside the cell or both?"

INFORMATION:

This research was supported by funding from National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants 1F30MH091998-01, AA017413, MH077791, and GM47969, FRAXA, the Simons Foundation, the McDonnell Center for Cellular and Molecular Neurobiology, and the Bantly Foundation.

Purgert CA, Izumi Y, Jong Y-J I, Kumar V, Zorumski CF, O'Malley KL. Intracellular mGluR5 can mediate synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus. The Journal of Neuroscience, March 25, 2014.

Washington University School of Medicine's 2,100 employed and volunteer faculty physicians also are the medical staff of Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children's hospitals. The School of Medicine is one of the leading medical research, teaching and patient-care institutions in the nation, currently ranked sixth in the nation by U.S. News & World Report. Through its affiliations with Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children's hospitals, the School of Medicine is linked to BJC HealthCare.

New clue to autism found inside brain cells

2014-03-26

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Counting calories in the fossil record

2014-03-26

Starting about 250 million years ago, at the end of the Permian period, brachiopod groups disappeared in large numbers, along with 90 percent of the planet's species. Today, only a few groups, or genera, of brachiopods remain. "Most people won't be familiar with brachiopods. They're pretty rare in the modern ocean," said Jonathan Payne, a paleobiologist at Stanford University.

Meanwhile, bivalves flourished, diversifying into a staggering variety of shapes and sizes, and spread from marine to freshwater habitats. "After the end-Permian mass extinction, we find far fewer ...

Last drinks: Brain's mechanism knows when to stop

2014-03-26

The study found a 'stop mechanism' that determined brain signals telling the individual to stop drinking water when no longer thirsty, and the brain effects of drinking more water than required.

Researcher Professor Derek Denton from the Faculty of Medicine, Dentistry and Health Sciences at the University of Melbourne said the study provided insight into the human instincts that determine survival behaviour and are also of medical importance.

"Different areas of the brain involved in emotional decision-making were activated when people drank water after becoming ...

Two spine surgeons are 3 times safer than 1

2014-03-26

Seattle, WA—A new team approach has improved safety—reducing rates of major complications by two thirds—for complex spinal reconstructive surgery for spinal deformity in adult Group Health patients at Virginia Mason Hospital & Seattle Medical Center. An article in the March issue of Spine Deformity gives a detailed description of the standardized protocol before, during, and after the surgery, stressing the new approach's three main features:

Two spine surgeons in the operating room

A live preoperative screening conference

Monitoring bleeding during the operation

The ...

ATHENA desktop human 'body' could reduce need for animal drug tests

2014-03-26

Creating surrogate human organs, coupled with insights from highly sensitive mass spectrometry technologies, a new project is on the brink of revolutionizing the way we screen new drugs and toxic agents.

ATHENA, the Advanced Tissue-engineered Human Ectypal Network Analyzer project team, is developing four human organ constructs – liver, heart, lung and kidney – that are based on a significantly miniaturized platform. Each organ component will be about the size of a smartphone screen, and the whole ATHENA "body" of interconnected organs would fit neatly on a desk.

"By ...

Life expectancy gains elude overweight teens

2014-03-26

Washington, DC—Although people live longer today than they did 50 years ago, people who were overweight and obese as teenagers aren't experiencing the same gains as other segments of the population, according to a new study published in the Endocrine Society's Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism (JCEM).

The life expectancy of the average American born in 2011 was 78.7 years, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The average lifespan has increased by more than a decade since 1950, but rising obesity rates threaten to take a toll on ...

Sugary drinks weigh heavily on teenage obesity

2014-03-26

New research shows sugary drinks are the worst offenders in the fight against youth obesity and recommends that B.C. schools fully implement healthy eating guidelines to reduce their consumption.

Data from the 2008 Adolescent Health survey among 11,000 grade seven to 12 students in British Columbia schools indicates sugary drinks like soda increased the odds of obesity more than other foods such as pizza, french fries, chips and candies.

The study, published today in the International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, found that students in schools ...

Research: Less invasive technique possible in vulvar cancer treatment

2014-03-26

A team of researchers from Women & Infants Hospital of Rhode Island commanded a national stage to present the results of a study evaluating the use of sentinel lymph node dissection in women with vulvar malignancies, and then follow the patients for complications and recurrence.

The team – Drs. Richard G. Moore, Dario Roque, Carolyn McCourt, Ashley Stuckey, Paul A. DiSIlvestro, James Sung, Margaret Steinhoff, Cornelius Granai III, and Katina Robison – presented their work at the annual meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Oncologists (SGO) in Tampa. The oral presentation ...

Lack of coronin 1 protein causes learning deficits and aggressive behavior

2014-03-26

This news release is available in German.

Organisms must be able to sense signals from the outside and translate these into biochemical cues in order to adequately respond to their environment. This capability is also required to process information that reaches the brain. Within the brain, stimulation of neurons activates genes that are required, for example for learning and memory. In collaboration with an international and interdisciplinary team the research group led by Prof. Jean Pieters from the Biozentrum, University of Basel, has now uncovered the role of ...

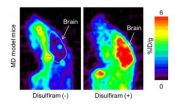

Using PET scanning to evaluate therapies of Menkes disease

2014-03-26

Scientists at the RIKEN Center for Life Science Technologies have used PET imaging to visualize the distribution in the body of copper, which is deregulated in Menkes disease, a genetic disorder, using a mouse model. This study lays the groundwork for PET imaging studies on human Menkes disease patients to identify new therapy options.

Menkes disease, though rare, is a fearsome genetic disorder. Most affected babies die within the first few years of life. The disease is caused by an inborn fault in the body's ability to absorb copper. The standard treatment today for ...

Diabetes: Good self-management helps to reduce mortality

2014-03-26

Scientists of the Institute of Health Economics and Health Care Management (IGM) and of the Institute of Epidemiology II (EPI II) at Helmholtz Zentrum München (HMGU), together with colleagues of the German Diabetes Center (DDZ) in Düsseldorf, investigated the association between self-management behavior and mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes. HMGU and the DDZ are partners in the German Center for Diabetes Research (DZD).

High self-management index – low mortality

340 study participants with type 2 diabetes were interviewed with regard to their patient behavior ...