(Press-News.org) JUPITER, FL – March 27, 2014 – Memories are difficult to produce, often fragile, and dependent on any number of factors—including changes to various types of nerves. In the common fruit fly—a scientific doppelganger used to study human memory formation—these changes take place in multiple parts of the insect brain.

Scientists from the Florida campus of The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) have been able to pinpoint a handful of neurons where certain types of memory formation occur, a mapping feat that one day could help scientists predict disease-damaged neurons in humans with the same specificity.

"What we found is that while a lot of the neurons will respond to sensory stimuli, only a certain subclass of neurons actually encodes the memory," said Seth Tomchik, a TSRI biologist who led the study, which was published March 27, 2014, online ahead of print by the journal Current Biology.

The researchers examined a type of neuron called dopaminergic neurons—which respond to dopamine, a well-known neurotransmitter—and are involved in shaping diverse behaviors, including learning, motivation, addiction and obesity.

In the study, the scientists followed the stimulation of a large number of these neurons when an odor was paired with an aversive event such as a mild electric shock. The scientists then used imaging technology to follow changes in the brains of live flies, mapping the activation patterns of signaling molecules within the neurons and observing learning-related plasticity—in which neurons change and develop memory traces.

The scientists found that the neurons that did encode memories responded to a cellular signaling messenger known as cAMP (cyclic adenosine monophosphate) that is vital for many biological processes. cAMP is involved in a number of psychological disorders such as bipolar disorder and schizophrenia, and its dysregulation may underlie some cognitive symptoms of Alzheimer's disease and Neurofibramatosis I.

In fact, the study pointed to a specific location in the brain—a particular lobe with a region known as the mushroom body—where the neurons appear to be particularly sensitive to elevated amounts of cAMP.

According to Tomchik, that's an important finding in terms of human memory because olfactory memory formation in the fruit fly is very similar to human memory formation.

"We have a good model in these two classes of neurons, one that encodes and one that doesn't," he said. "Now we know exactly where the memory formation should be and where to look to see how disease may disrupt it."

Tamara Boto, the first author of the study and a member of Tomchik's laboratory, added, "We know where, but we don't yet know the mechanism of why only these subsets are affected. That's our next job—to figure that out."

INFORMATION:

In addition to Tomchik and Boto, authors of the study, "Dopaminergic Modulation of Camp Drives Nonlinear Plasticity Across the Drosophila Mushroom Body Lobes," are Thierry Louis and Kantiya Jindachomthong of TSRI; and Kees Jalink of The Netherlands Cancer Institute, Amsterdam.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant MH092294).

About The Scripps Research Institute:

The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) is one of the world's largest independent, not-for-profit organizations focusing on research in the biomedical sciences. TSRI is internationally recognized for its contributions to science and health, including its role in laying the foundation for new treatments for cancer, rheumatoid arthritis, hemophilia, and other diseases. An institution that evolved from the Scripps Metabolic Clinic founded by philanthropist Ellen Browning Scripps in 1924, the institute now employs about 3,000 people on its campuses in La Jolla, CA, and Jupiter, FL, where its renowned scientists—including three Nobel laureates—work toward their next discoveries. The institute's graduate program, which awards PhD degrees in biology and chemistry, ranks among the top ten of its kind in the nation. For more information, see http://www.scripps.edu.

Once available to the public, this and other press releases are posted on the TSRI website at http://www.scripps.edu/news/newsreleases.html

In mapping feat, Scripps Florida scientists pinpoint neurons where select memories grow

2014-03-27

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Foraging bats can warn each other away from their dinners

2014-03-27

VIDEO:

In this animated graphic of bats' calls in flight, two bats are represented by different colors, red and blue. The bats' movements and vocalizations have been slowed by a factor...

Click here for more information.

Look into the spring sky at dusk and you may see flitting groups of bats, gobbling up insect meals in an intricately choreographed aerial dance. It's well known that echolocation calls keep the bats from hitting trees and each other. But now scientists have learned ...

Researchers at IRB discover a key regulator of colon cancer

2014-03-27

Barcelona, Thursday 27 March 2014.- A team headed by Angel R. Nebreda at the Institute for Research in Biomedicine (IRB) identifies a dual role of the p38 protein in colon cancer. The study demonstrates that, on the one hand, p38 is important for the optimal maintenance of the epithelial barrier that protects the intestine against toxic agents, thus contributing to decreased tumour development. Intriguingly, on the other hand, once a tumour has formed, p38 is required for the survival and proliferation of colon cancer cells, thus favouring tumour growth. The study is published ...

Researchers: Biomarkers predict effectiveness of radiation treatments for cancer

2014-03-27

An international team of researchers, led by Beaumont Health System's Jan Akervall, M.D., Ph.D., looked at biomarkers to determine the effectiveness of radiation treatments for patients with squamous cell cancer of the head and neck. They identified two markers that were good at predicting a patient's resistance to radiation therapy. Their findings were published in the February issue of the European Journal of Cancer.

Explains Dr. Akervall, co-director, Head and Neck Cancer Multidisciplinary Clinic, Beaumont Hospital, Royal Oak, and clinical director of Beaumont's BioBank, ...

Cancer researchers find key protein link

2014-03-27

HOUSTON – (March 27, 2014) – A new understanding of proteins at the nexus of a cell's decision to survive or die has implications for researchers who study cancer and age-related diseases, according to biophysicists at the Rice University-based Center for Theoretical Biological Physics (CTBP).

Experiments and computer analysis of two key proteins revealed a previously unknown binding interface that could be addressed by medication. Results of the research appear this week in an open-source paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The proteins ...

Sleep may stop chronic pain sufferers from becoming 'zombies'

2014-03-27

Chronic pain sufferers could be kept physically active by improving the quality of their sleep, new research suggests.

The study by the University of Warwick's Department of Psychology, published in PLoS One, found that sleep was a worthy target for treating chronic pain and not only as an answer to pain-related insomnia.

"Engaging in physical activity is a key treatment process in pain management. Very often, clinicians would prescribe exercise classes, physiotherapy, walking and cycling programmes as part of the treatment, but who would like to engage in these activities ...

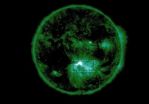

First sightings of solar flare phenomena confirm 3-D models of space weather

2014-03-27

Scientists have for the first time witnessed the mechanism behind explosive energy releases in the Sun's atmosphere, confirming new theories about how solar flares are created.

New footage put together by an international team led by University of Cambridge researchers shows how entangled magnetic field lines looping from the Sun's surface slip around each other and lead to an eruption 35 times the size of the Earth and an explosive release of magnetic energy into space.

The discoveries of a gigantic energy build-up bring us a step closer to predicting when and where ...

Corporate layoff strategies are increasing workplace gender and racial inequality

2014-03-27

Research from Prof. Alexandra Kalev of Tel Aviv University's Department of Sociology and Anthropology reveals that current workplace downsizing policies are reducing managerial diversity and increasing racial and gender inequalities. According to the study, layoff practices focusing on positions and tenure, rather than worker performance, minimized the share of white women in management positions by 25 percent and of black men by 20 percent. Prof. Kalev found that a striking two-thirds of the companies surveyed used tenure or position as their core criteria for downsizing. ...

Instituting a culture of professionalism

2014-03-27

Boston, MA—There is a growing recognition that in health care institutions where professionalism is not embraced and expectations of acceptable behaviors are not clear and enforced, an increase in medical errors and adverse events and a deterioration in safe working conditions can occur. In 2008 Brigham and Women's Hospital (BWH) created the Center for Professionalism and Peer Support (CPPS) and has seen tremendous success in this initiative. Researchers recently analyzed data from the CPPS from 2010 through 2013 and found that employees continue to turn to the center for ...

Controlling electron spins by light

2014-03-27

This news release is available in German.

The material class of topological insulators has been discovered a few years ago and displays amazing properties: In their inside, they behave electrically insulating but at their surface they form metallic, conducting states. The electron spin, i. e., their intrinsic angular momentum, is playing a decisive role. Their sense of rotation is directly coupled to their direction of movement. This coupling leads not only to a high stability of the metallic property but also enables a particularly lossless electrical conduction. ...

To grow or not to grow: a step forward in adult vertebrate tissue regeneration

2014-03-27

The reason why some animals can regenerate tissues after severe organ loss or amputation while others, such as humans, cannot renew some structures has always intrigued scientists. In a study now published in PLOS ONE*, a research group from Instituto Gulbenkian de Ciência (IGC, Portugal) led by Joaquín Rodríguez León provided new clues to solve this central question by investigating regeneration in an adult vertebrate model: the zebrafish. It was known that zebrafish is able to regenerate organs, and that electrical currents may play a role in this process, but the exact ...