(Press-News.org) DURHAM, N.C. – Duke Medicine researchers studying tiny, antennae-like structures called cilia have found a potential way to ease some of the physical damage of numerous genetic disorders that result when these essential cellular components are defective.

Different genetic defects cause dysfunction of the cilia, which often act as sensory organs that receive signals from other cells. Individually, disorders involving cilia are rare, but collectively the more than 100 diseases in the category known as ciliopathies affect as many as one in 1,000 people. Ciliopathies are characterized by cognitive impairment, blindness, deafness, kidney and heart disease, infertility, obesity and diabetes.

Recent research has added key insights into the overall role and function of cilia in cells and what occurs when the organelle is defective.

"Cilia are required for regulation of a whole host of signaling pathways for cellular development," said Nicholas Katsanis, PhD, professor of cell biology and director of the Center for Human Disease Modeling at Duke. "They are not the only signaling regulators, but they are critical. It's been important for us to understand how they do this."

In the current study, published April 1, 2014, in the Journal of Clinical Investigation, Katsanis and colleagues describe a common mechanism that appears to account for how dysfunctional cilia cause so many different problems in cellular signaling pathways.

Using both cells and animal models, they focused on the ubiquitin-proteasome system, the cell's machinery tasked with regulating the cellular environment by breaking down proteins that are either damaged or in need of removal.

"Imagine regular housekeeping" Katsanis said. "Taking out waste is part and parcel to the process, but not if you end up throwing away your valuables."

The researchers also set out to test whether they could somehow bolster the function of the proteasome to see if this would have a therapeutic effect. When non-defective genes were introduced in zebrafish, the animals showed physical improvements indicative of corrections in multiple signaling pathways, Katsanis said.

More significantly, similar improvements occurred in the animals by administering common compounds, including mevalonic acid and the nutritional supplement sulforaphane, an antioxidant found in broccoli and other cruciferous vegetables. Both are known to improve proteasomal activity.

"While the animals were not as good as normal controls, they were much better – we saw clear physical improvement with each of the compounds," Katsanis said. "This now gives us a hypothesis that explains at least in part why, for whatever reason ciliopathy is caused, it can result in different signaling pathways going awry, and a potential avenue for therapies."

Katsanis said additional research should focus on the proteasome system, and other potential therapeutic targets that could improve the proteasome.

"Understanding cilia dysfunction is important, because its association with so many disorders pose a significant societal and medical burden. And we look forward to seeing wither the insights we have learned in these studies are applicable to other diseases," Katsanis said, adding that more work will be required to follow up this lead.

"As exciting as these findings are, we need to act cautiously and responsibly before we jump into clinical trials in humans," he said. "Nonetheless, there is now a clear path toward that goal."

INFORMATION:

In addition to Katsanis, study authors from Duke include Yangfan P. Liu, I-Chun Tsai, Edwin C. Oh and David S. Parker. Additional authors included Manuela Morleo, Filomena Massa and Brunella Franco of Telethon Institute of Genetics and Medicine in Italy; Carmen C. Leitch and Norann A. Zaghloul, of University of Maryland School of Medicine; and Byung-Hoon Lee and Daniel Finley of Harvard Medical School.

The study was funded in part by National Institutes of Health grants (R37GM04360, R01HD04260, R01DK072301 and R01DK075972); additional funding support is listed in the publication.

Common molecular defect offers treatment hope for group of rare disorders

2014-04-01

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Swimming pool urine combines with chlorine to pose health risks

2014-04-01

WEST LAFAYETTE, Ind. - A new study shows how uric acid in urine generates potentially hazardous "volatile disinfection byproducts" in swimming pools by interacting with chlorine, and researchers are advising swimmers to observe "improved hygiene habits."

Chlorination is used primarily to prevent pathogenic microorganisms from growing. The disinfection byproducts include cyanogen chloride (CNCl) and trichloramine (NCl3). Cyanogen chloride is a toxic compound that affects many organs, including the lungs, heart and central nervous system by inhalation. Trichloramine has ...

Got acne? There's an App for that!

2014-04-01

CHICAGO --- Acne sufferers around the world are using an iPhone app created at Northwestern University to learn how certain foods affect their skin conditions.

The app, called "diet & acne," can be downloaded from the iTunes app store for free. It uses data from a systematic analysis of peer-reviewed research studies to show people if there is or is not scientific evidence linking acne to foods such as chocolate, fat, sugar and whey protein.

"Users may be surprised to learn that there is no conclusive evidence from large randomized controlled trials that have linked ...

Plugged in but powered down

2014-04-01

It's not news that being a couch potato is bad for your health. Lack of physical activity is associated with a range of diseases from diabetes to heart attacks. It now turns out that young men who have experienced depression early in life may be especially vulnerable to becoming sedentary later in life. And particularly to spending large amounts of time online each day.

A study of 761 adults in Montreal who were identified at the age of 20 as suffering from the symptoms of depression (in 2007-08) were asked by researchers to keep track of how much leisure time they spent ...

Good vibrations: Using light-heated water to deliver drugs

2014-04-01

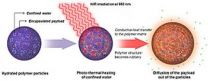

Researchers from the University of California, San Diego Skaggs School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, in collaboration with materials scientists, engineers and neurobiologists, have discovered a new mechanism for using light to activate drug-delivering nanoparticles and other targeted therapeutic substances inside the body.

This discovery represents a major innovation, said Adah Almutairi, PhD, associate professor and director of the joint UC San Diego-KACST Center of Excellence in Nanomedicine. Up to now, she said, only a handful of strategies using light-triggered ...

NASA caught Tropical Cyclone Hellen's rainfall near peak

2014-04-01

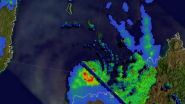

VIDEO:

This 3-D simulated flyby of Tropical Cyclone Hellen on March 30, showed some powerful storms in Hellen's eye wall were reaching heights of over 13 km/8 miles.

Click here for more information.

When Tropical Cyclone Hellen was near the "peak of her career" NASA's TRMM satellite picked up on her popularity in terms of tropical rainfall. Hellen was a very heavy rainmaker in her heyday with heavy rain rates. Hellen weakened to a remnant low pressure area by April 1, but has ...

Low sodium levels pre-transplant does not affect liver transplant recipient survival

2014-04-01

Researchers report that low levels of sodium, known as hyponatremia, prior to transplantation does not increase the risk of death following liver transplant. Full findings are published in Liver Transplantation, a journal of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the International Liver Transplantation Society.

Medical evidence shows that low sodium concentration is common in patients with end stage liver disease (ESLD), with roughly half of those with cirrhosis having sodium levels below the normal range of 135-145 mmol/L. Moreover, previous research ...

Study finds link between child's obesity and cognitive function

2014-04-01

URBANA, Ill. – A new University of Illinois study finds that obese children are slower than healthy-weight children to recognize when they have made an error and correct it. The research is the first to show that weight status not only affects how quickly children react to stimuli but also impacts the level of activity that occurs in the cerebral cortex during action monitoring.

"I like to explain action monitoring this way: when you're typing, you don't have to be looking at your keyboard or your screen to realize that you've made a keystroke error. That's because action ...

Misleading mineral may have resulted in overestimate of water in moon

2014-04-01

The amount of water present in the moon may have been overestimated by scientists studying the mineral apatite, says a team of researchers led by Jeremy Boyce of the UCLA Department of Earth, Planetary and Space Sciences.

Boyce and his colleagues created a computer model to accurately predict how apatite would have crystallized from cooling bodies of lunar magma early in the moon's history. Their simulations revealed that the unusually hydrogen-rich apatite crystals observed in many lunar rock samples may not have formed within a water-rich environment, as was originally ...

Monkey caloric restriction study shows big benefit; contradicts earlier study

2014-04-01

MADISON, Wis. – The latest results from a 25-year study of diet and aging in monkeys shows a significant reduction in mortality and in age-associated diseases among those with calorie-restricted diets. The study, begun at the University of Wisconsin-Madison in 1989, is one of two ongoing, long-term U.S. efforts to examine the effects of a reduced-calorie diet on nonhuman primates.

The study of 76 rhesus monkeys, reported Monday in Nature Communications, was performed at the Wisconsin National Primate Research Center in Madison. When they were 7 to 14 years of age, the ...

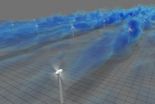

Wind energy: On the grid, off the checkerboard

2014-04-01

WASHINGTON D.C., April 1, 2014 -- As wind farms grow in importance across the globe as sources of clean, renewable energy, one key consideration in their construction is their physical design -- spacing and orienting individual turbines to maximize their efficiency and minimize any "wake effects," where the swooping blades of one reduces the energy in the wind available for the following turbine.

Optimally spacing turbines allows them to capture more wind, produce more power and increase revenue for the farm. Knowing this, designers in the industry typically apply simple ...