(Press-News.org) Right now, options are limited for preventing heart attacks. However, the day may come when treatments target the heart attack gene, myeloid related protein-14 (MRP-14, also known as S100A9) and defang its ability to produce heart attack-inducing blood clots, a process referred to as thrombosis.

Scientists at Case Western Reserve School of Medicine and University Hospitals Case Medical Center have reached a groundbreaking milestone toward this goal. They have studied humans and mice and discovered how MRP-14 generates dangerous clots that could trigger heart attack or stroke, and what happens by manipulating MRP-14. This study describes a previously unrecognized platelet-dependent pathway of thrombosis. The results of this research will appear in the April edition of the Journal for Clinical Investigation (JCI).

"This is exciting because we have now closed the loop of our original finding that MRP-14 is a heart attack gene," said Daniel I. Simon, MD, the Herman K. Hellerstein Professor of Cardiovascular Research and Medicine at the School of Medicine and director of the University Hospitals Harrington Heart & Vascular Institute. "We now describe a whole new pathway that shows clotting platelets have MRP-14 inside them, that platelets secrete MRP-14 and that MRP-14 binds to a platelet receptor called CD36 to activate platelets."

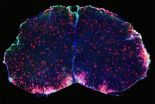

This translational research has moved back and forth from the cardiac catheterization laboratory investigating patients presenting with heart attack to the basic research lab probing mechanisms of disease. The clinical portion of this research yielded a visually stunning element—blood clots extracted from an occluded heart artery loaded with MRP-14 containing platelets.

"It is remarkable that this abundant platelet protein promoting thrombosis could have gone undetected until now," Simon said.

In detailed studies using MRP-14-deficient mice, the investigators discovered MRP-14 in action. One key finding is that, while MRP-14 is required for pathologic blood clotting, it does not appear to be involved in the natural, primary hemostasis response to prevent bleeding.

"The practical significance of this research is that it may provide a new target to develop more effective and safer anti-thrombotic agents," Simon said. Current anti-clotting drugs are subject to significant bleeding risk, which is associated with increased mortality.

"If we could develop an agent that affects pathologic clotting and not hemostasis, that would be a home run," Simon said. "You would have a safer medication to treat pathologic clotting in heart attack and stroke."

INFORMATION:

Funding for this project came from the National Institutes of Health (HL086672, HL052779, HL85816 and HL57506 MERIT Award), Case Western Reserve University Cardiovascular Research Institute and University Hospitals.

About Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine

Founded in 1843, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine is the largest medical research institution in Ohio and is among the nation's top medical schools for research funding from the National Institutes of Health. The School of Medicine is recognized throughout the international medical community for outstanding achievements in teaching. The School's innovative and pioneering Western Reserve2 curriculum interweaves four themes--research and scholarship, clinical mastery, leadership, and civic professionalism--to prepare students for the practice of evidence-based medicine in the rapidly changing health care environment of the 21st century. Nine Nobel Laureates have been affiliated with the School of Medicine.

Annually, the School of Medicine trains more than 800 MD and MD/PhD students and ranks in the top 25 among U.S. research-oriented medical schools as designated by U.S. News & World Report's "Guide to Graduate Education."

The School of Medicine's primary affiliate is University Hospitals Case Medical Center and is additionally affiliated with MetroHealth Medical Center, the Louis Stokes Cleveland Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center, and the Cleveland Clinic, with which it established the Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine of Case Western Reserve University in 2002. http://casemed.case.edu

About University Hospitals

University Hospitals, the second largest employer in Northeast Ohio, serves the needs of patients through an integrated network of hospitals, outpatient centers and primary care physicians in 16 counties. At the core of our health system is University Hospitals Case Medical Center, one of only 18 hospitals in the country to have been named to U.S. News & World Report's most exclusive rankings list: the Best Hospitals 2013-14 Honor Roll. The primary affiliate of Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, UH Case Medical Center is home to some of the most prestigious clinical and research centers of excellence in the nation and the world, including cancer, pediatrics, women's health, orthopaedics and spine, radiology and radiation oncology, neurosurgery and neuroscience, cardiology and cardiovascular surgery, organ transplantation and human genetics. Its main campus includes the internationally celebrated UH Rainbow Babies & Children's Hospital, ranked among the top children's hospitals in the nation; UH MacDonald Women's Hospital, Ohio's only hospital for women; and UH Seidman Cancer Center, part of the NCI-designated Case Comprehensive Cancer Center at Case Western Reserve University. UH Case Medical Center is the 2012 recipient of the American Hospital Association – McKesson Quest for Quality Prize for its leadership and innovation in quality improvement and safety. For more information, go to http://www.uhhospitals.org

Heart attack gene, MRP-14, triggers blood clot formation

Discovery could lead to more effective therapies to prevent heart attacks

2014-04-02

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Will roe deer persist? Climate change spells disaster for species unable to keep up

2014-04-02

As the climate continues to change, it's unclear to what extent different species will be able to keep pace with altered temperatures and shifted seasons. Living organisms are the survivors of previous environmental changes and might therefore be expected to adapt, but are there limits?

According to research to be published in the Open Access journal PLOS Biology on April 1, some species may be much less able to cope with the effects of climate change than previously thought. The study, by Floriane Plard, Jean-Michel Gaillard, Christophe Bonenfant and colleagues, looked ...

Age-related decline in sleep quality might be reversible

2014-04-02

Sleep is essential for human health. But with increasing age, many people experience a decline in sleep quality, which in turn reduces their quality of life. In a new study publishing April 1 in the Open Access journal PLOS Biology, Scientists at the Max Planck Institute (MPI) for Biology of Ageing in Cologne have investigated the mechanisms by which ageing impairs sleep in the fruit fly. Their findings suggest that age-related sleep decline can be prevented and might even be reversible.

To uncover basic age-related sleep mechanisms, the Max Planck scientists studied the ...

Enhancers serve to restrict potentially dangerous hypermutation to antibody genes

2014-04-02

How B lymphocytes are able to direct mutations to their antibody genes to produce millions of different antibodies has fascinated biologists for decades. A new study publishing in the Open Access journal PLOS Biology on April 1 by Buerstedde and colleagues shows that this process of programed, spatially targeted genome mutation (aka. somatic hypermutation) is controlled by nearby transcription regulatory sequences called enhancers. Enhancers are usually known to control gene transcription, and these antibody enhancers are now shown to also act in marking the antibody genes ...

Going batty for jumping DNA as a cause of species diversity

2014-04-02

The vesper bats are the largest and best-known common family of bats, with more than 400 species spread across the globe, ranking second among mammals in species diversity.

Authors Ray et al., wanted to get at the root cause of this diversity by taking advantage of two vesper bat species whose genomes have recently been sequenced. They speculated that one cause of this diversity might be jumping elements in the genome, called DNA transposons, which are more active and recent in the evolutionary history of this family than any other mammal. Why and how this DNA transposon ...

Likely culprit in spread of colon cancer identified

2014-04-02

New research at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis and Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville has implicated a poorly understood protein called PLAC8 in the spread of colon cancer.

While elevated PLAC8 levels were known to be associated with colon cancer, the researchers now have shown that the protein plays an active role in shifting normal cells lining the colon into a state that encourages metastasis.

The work appears April 1 in the Journal of Clinical Investigation.

"We knew levels of this protein are elevated in colon cancer," said ...

Gene therapy improves limb function following spinal cord injury

2014-04-02

Delivering a single injection of a scar-busting gene therapy to the spinal cord of rats following injury promotes the survival of nerve cells and improves hind limb function within weeks, according to a study published April 2 in The Journal of Neuroscience. The findings suggest that, with more confirming research in animals and humans, gene therapy may hold the potential to one day treat people with spinal cord injuries.

The spinal cord is the main channel through which information passes between the brain and the rest of the body. Most spinal cord injuries are caused ...

Mode of action of new multiple sclerosis drug discovered

2014-04-02

This news release is available in German. Just a few short weeks ago, dimethyl fumarate was approved in Europe as a basic therapy for multiple sclerosis. Although its efficacy has been established in clinical studies, its underlying mode of action was still unknown, but scientists from Bad Nauheim's Max Planck Institute for Heart and Lung Research and the University of Lübeck have now managed to decode it. They hope that this knowledge will help them develop more effective therapeutic agents.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic inflammatory disease of the central ...

Well-rested flies

2014-04-02

This news release is available in German. Elderly flies do not sleep well – they frequently wake up during the night and wander around restlessly. The same is true of humans. For researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Biology of Ageing in Cologne, the sleeplessness experienced by the fruit fly Drosophila is therefore a model case for human sleeping behaviour. The scientists have now discovered molecules in the flies' cells that affect how the animals sleep in old age: if insulin/IGF signalling is active, the quality of the animals' sleep is reduced and they wake ...

Penn Medicine points to new ways to prevent relapse in cocaine-addicted patients

2014-04-02

(PHILADELPHIA) – Relapse is the most painful and expensive feature of drug addiction—even after addicted individuals have been drug-free for months or years, the likelihood of sliding back into the habit remains high. The National Institute on Drug Abuse estimates that 40 to 60 percent of addicted individuals will relapse, and in some studies the rates are as high as 80 percent at six months after treatment. Though some relapse triggers can be consciously avoided, such as people, places and things related to drug use, other subconscious triggers related to the brain's reward ...

The mammography dilemma

2014-04-01

A comprehensive review of 50 year's worth of international studies assessing the benefits and harms of mammography screening suggests that the benefits of the screening are often overestimated, while harms are underestimated. And, since the relative benefits and harms of screening are related to a complex array of clinical factors and personal preferences, physicians and patients need more guidance on how best to individualize their approach to breast cancer screening.

The results of the review by researchers at Harvard Medical School's Department of Health Care Policy ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Scientists discover why we know when to stop scratching an itch

A hidden reason inner ear cells die – and what it means for preventing hearing loss

Researchers discover how tuberculosis bacteria use a “stealth” mechanism to evade the immune system

New microscopy technique lets scientists see cells in unprecedented detail and color

Sometimes less is more: Scientists rethink how to pack medicine into tiny delivery capsules

Scientists build low-cost microscope to study living cells in zero gravity

The Biophysical Journal names Denis V. Titov the 2025 Paper of the Year-Early Career Investigator awardee

Scientists show how your body senses cold—and why menthol feels cool

Scientists deliver new molecule for getting DNA into cells

Study reveals insights about brain regions linked to OCD, informing potential treatments

Does ocean saltiness influence El Niño?

2026 Young Investigators: ONR celebrates new talent tackling warfighter challenges

Genetics help explain who gets the ‘telltale tingle’ from music, art and literature

Many Americans misunderstand medical aid in dying laws

Researchers publish landmark infectious disease study in ‘Science’

New NSF award supports innovative role-playing game approach to strengthening research security in academia

Kumar named to ACMA Emerging Leaders Program for 2026

AI language models could transform aquatic environmental risk assessment

New isotope tools reveal hidden pathways reshaping the global nitrogen cycle

Study reveals how antibiotic structure controls removal from water using biochar

Why chronic pain lasts longer in women: Immune cells offer clues

Toxic exposure creates epigenetic disease risk over 20 generations

More time spent on social media linked to steroid use intentions among boys and men

New study suggests a “kick it while it’s down” approach to cancer treatment could improve cure rates

Milken Institute, Ann Theodore Foundation launch new grant to support clinical trial for potential sarcoidosis treatment

New strategies boost effectiveness of CAR-NK therapy against cancer

Study: Adolescent cannabis use linked to doubling risk of psychotic and bipolar disorders

Invisible harms: drug-related deaths spike after hurricanes and tropical storms

Adolescent cannabis use and risk of psychotic, bipolar, depressive, and anxiety disorders

Anxiety, depression, and care barriers in adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities

[Press-News.org] Heart attack gene, MRP-14, triggers blood clot formationDiscovery could lead to more effective therapies to prevent heart attacks