(Press-News.org) CAMBRIDGE, Mass-- The electrochemical reactions inside the porous electrodes of batteries and fuel cells have been described by theorists, but never measured directly. Now, a team at MIT has figured out a way to measure the fundamental charge transfer rate — finding some significant surprises.

The study found that the Butler-Volmer (BV) equation, usually used to describe reaction rates in electrodes, is inaccurate, especially at higher voltage levels. Instead, a different approach, called Marcus-Hush-Chidsey charge-transfer theory, provides more realistic results — revealing that the limiting step of these reactions is not what had been thought.

The new findings could help engineers design better electrodes to improve batteries' rates of charging and discharging, and provide a better understanding of other electrochemical processes, such as how to control corrosion. The work is described this week in the journal Nature Communications by MIT postdoc Peng Bai and professor of chemical engineering and mathematics Martin Bazant.

Previous work was based on the assumption that the performance of electrodes made of lithium iron phosphate — widely used in lithium-ion batteries — was limited primarily by how fast lithium ions would diffuse into the solid electrode from the liquid electrolyte. But the new analysis shows that the critical interface is actually between two solid materials: the electrode itself, and a carbon coating used to improve its performance.

Limited by electron transfer

Bai and Bazant's analysis shows that both transport steps in solid and liquid — ion migration in the electrolyte, and diffusion of "quasiparticles" called polarons — are very fast, and therefore do not limit battery performance. "We show it's actually electrons, not the ions, transferring at the solid-solid interface," Bai says, that determine the rate.

Bazant says researchers had not suspected, despite extensive research on lithium iron phosphate, that the material's electrochemical reactions might be limited by electron transfer between two solids. "That's a completely new picture for this material; it's not something that has even been mentioned before," he says.

While coating the electrode surface with a thin layer of carbon or graphene had been shown to improve performance, there was no microscopic and quantitative understanding of why this made a difference, Bazant says. The new findings will help explain a number of apparently conflicting results in the scientific literature, he says.

Unexpectedly low reaction rates

For example, the classical equations used to predict the performance of such materials have indicated that the logarithm of the reaction rate should vary linearly as voltage is increased — but experiments have shown a nonlinear response, with the uptake of lithium flattening out at high voltage. The discrepancies have been significant, Bazant says: "We find the reaction rate is much lower than what is predicted."

The new analysis means that to make further improvements in this technology, the focus should be on "how you engineer the surface" at the solid-solid interface, Bai says.

Bazant adds that the new understanding could have implications far beyond electrode design, since the fundamental processes the team uncovered apply to electrochemical processes including electrodeposition, corrosion, and fuel cells. "It's also important for basic science," he says, since the process is both ubiquitous and poorly understood.

The BV equation is purely empirical, and "doesn't tell you anything about what's going on microscopically," Bazant says. By contrast, the Marcus-Hush-Chidsey equations — for which Rudolph Marcus of the California Institute of Technology was awarded the 1992 Nobel Prize in chemistry — are based on a precise understanding of atomic-level activity. So the new analysis, Bazant maintains, could lead not only to new practical solutions, but also to a deeper understanding of the underlying mechanisms.

INFORMATION:

Written by David Chandler, MIT News Office

How electrodes charge and discharge

Analysis probes reactions in porous battery electrodes for the first time

2014-04-03

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

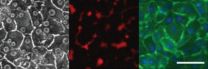

An ultrathin collagen matrix biomaterial tool for 3D microtissue engineering

2014-04-03

A novel ultrathin collagen matrix assembly allows for the unprecedented maintenance of liver cell morphology and function in a microscale "organ-on-a-chip" device that is one example of 3D microtissue engineering.

A team of researchers from the Center for Engineering in Medicine at the Massachusetts General Hospital have demonstrated a new nanoscale matrix biomaterial assembly that can maintain liver cell morphology and function in microfluidic devices for longer times than has been previously been reported in microfluidic devices. This technology allows researchers to ...

Immune cell defenders protect us from bacteria invasion

2014-04-03

The patented work, published in Nature today, provides a deeper understanding of our first line of defence, and what happens when it goes wrong. It will lead to new ways of diagnosing and treating inflammatory bowel disease, peptic ulcers and even TB. It could also lead to novel protective vaccines.

The discovery is the result of national and international collaboration between the universities of Melbourne, Monash, Queensland and Cork. It also depended on access to major facilities including the Australian Synchrotron and the Bio21 Institute.

One of the leads in the ...

Women entrepreneurs have limited chances to lead their new businesses

2014-04-03

Women who start new businesses with men have limited opportunities to move into leadership roles, according to sociologists at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; and when they co-found a business with their husbands, they have even fewer chances to be in charge.

The study, published in the April issue of the American Sociological Review, comes on the heels of a recent debate about businesses with all-male boards of directors and adds to a growing body of knowledge that documents women's limited access to leadership roles in the business world.

"This work ...

Women do not apply to 'male-sounding' job postings

2014-04-03

This news release is available in German. "We don't have many women in management roles because we get so few good applicants." Companies can be heard lamenting this state of affairs with increasing frequency. Just an excuse? Scientists from the TUM have discovered something that actually does deter women from applying for a job, even if they are qualified: the wording of the job ads.

The scientists showed some 260 test subjects fictional employment ads. These included, for example, a place in a training program for potential management positions. If the advertisement ...

Forward Looks report available 'Media in Europe: New Questions for Research and Policy'

2014-04-03

A new report from the European Science Foundation, 'Media in Europe: New Questions for Research and Policy', examines the field of media studies and proposes an agenda for research for the next decade

From newspapers and radio to internet, mobile telephony and digital communications, the media have in recent decades become ever more central to people's activities in personal, professional and social life. In this period of rapid social and technological change, it can be difficult to separate what we really know about the media from our assumptions and feelings about ...

Resting-state functional connection during low back pain

2014-04-03

The default mode network is a key area in the resting state, involving the posterior cingulate cortex, precuneus, medial prefrontal and lateral temporal cortices, and is characterized by balanced positive and negative connections classified as the "hubs" of structural and functional connectivity in brain studies. Resting-state functional connectivity MRI is based on the observation that brain regions exhibit correlated slow fluctuations at rest, and has become a widely used tool for investigating spontaneous brain activity. Functional magnetic resonance imaging studies ...

Researcher: Chowing down on watermelon could lower blood pressure

2014-04-03

TALLAHASSEE, Fla. — Be sure to pick up a watermelon — or two — at your neighborhood farmers' market.

It could save your life.

A new study by Florida State University Associate Professor Arturo Figueroa, published in the American Journal of Hypertension, found that watermelon could significantly reduce blood pressure in overweight individuals both at rest and while under stress.

"The pressure on the aorta and on the heart decreased after consuming watermelon extract," Figueroa said.

The study started with a simple concept. More people die of heart attacks in cold ...

UCSB researchers create first regional Ocean Health Index

2014-04-03

With one of the world's longest coastlines, spanning 17 states, and very high marine and coastal biodiversity, Brazil owes much of its prosperity to the ocean. For that reason, Brazil was the site of the first Ocean Health Index regional assessment designed to evaluate the economic, social and ecological uses and benefits that people derive from the ocean. Brazil's overall score in the national study was 60 out of 100.

The findings from that study — conducted by researchers from UC Santa Barbara's National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis (NCEAS), the Department ...

Immune cell 'defenders' could beat invading bacteria

2014-04-03

An international team of scientists has identified the precise biochemical key that wakes up the body's immune cells and sends them into action against invading bacteria and fungi.

The patented work, published in Nature today, provides the starting point to understanding our first line of defence, and what happens when it goes wrong. It will lead to new ways of diagnosing and treating inflammatory bowel disease, peptic ulcers and even TB. It could also lead to new protective vaccines.

The discovery, the result of an international collaboration between Monash University ...

'Homo' is the only primate whose tooth size decreases as its brain size increases

2014-04-03

Andalusian researchers, led by the University of Granada, have discovered a curious characteristic of the members of the human lineage, classed as the genus Homo: they are the only primates where, throughout their 2.5-million year history, the size of their teeth has decreased alongside the increase in their brain size.

The key to this phenomenon, which scientists call "evolutionary paradox", could be in how Homo's diet has evolved. Digestion starts first in the mouth and, so, teeth are essential in breaking food down into smaller pieces. Therefore, the normal scenario ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Mangrove forests are short of breath

Low testosterone, high fructose: A recipe for liver disaster

SKKU research team unravels the origin of stochasticity, a key to next-generation data security and computing

Flexible polymer‑based electronics for human health monitoring: A safety‑level‑oriented review of materials and applications

Could ultrasound help save hedgehogs?

attexis RCT shows clinically relevant reduction in adult ADHD symptoms and is published in Psychological Medicine

Cellular changes linked to depression related fatigue

First degree female relatives’ suicidal intentions may influence women’s suicide risk

Specific gut bacteria species (R inulinivorans) linked to muscle strength

Wegovy may have highest ‘eye stroke’ and sight loss risk of semaglutide GLP-1 agonists

New African species confirms evolutionary origin of magic mushrooms

Mining the dark transcriptome: University of Toronto Engineering researchers create the first potential drug molecules from long noncoding RNA

IU researchers identify clotting protein as potential target in pancreatic cancer

Human moral agency irreplaceable in the era of artificial intelligence

Racial, political cues on social media shape TV audiences’ choices

New model offers ‘clear path’ to keeping clean water flowing in rural Africa

Ochsner MD Anderson to be first in the southern U.S. to offer precision cancer radiation treatment

Newly transferred jumping genes drive lethal mutations

Where wells run deep, biodiversity runs thin

Q&A: Gassing up bioengineered materials for wound healing

From genetics to AI: Integrated approaches to decoding human language in the brain

Leora Westbrook appointed executive director of NR2F1 Foundation

Massive-scale spatial multiplexing with 3D-printed photonic lanterns achieved by researchers

Younger stroke survivors face greater concentration, mental health challenges — especially those not employed

From chatbots to assembly lines: the impact of AI on workplace safety

Low testosterone levels may be associated with increased risk of prostate cancer progression during surveillance

Analysis of ancient parrot DNA reveals sophisticated, long-distance animal trade network that pre-dates the Inca Empire

How does snow gather on a roof?

Modeling how pollen flows through urban areas

Blood test predicts dementia in women as many as 25 years before symptoms begin

[Press-News.org] How electrodes charge and dischargeAnalysis probes reactions in porous battery electrodes for the first time