(Press-News.org) CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — Crops that produce more while using less water seem like a dream for a world with a burgeoning population and already strained food and water resources. This dream is coming closer to reality for University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign researchers who have developed a new computer model that can help plant scientists breed better soybean crops.

Under current climate conditions, the model predicts a design for a soybean crop with 8.5 percent more productivity, but using 13 percent less water, and reflecting 34 percent more radiation back into space, by breeding for slightly different leaf distribution, angles and reflectivity. This work appears in the journal Global Change Biology.

"The model lets you look at one of those goals individually or all of them simultaneously," said Praveen Kumar, a co-author of the study who is the Lovell Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering at Illinois. "There might be some areas where you look at only one aspect – if you're in an arid zone, you can structure things to maximize the water efficiency. In other areas you may want to concentrate on food productivity."

Plants have evolved to outcompete other plants – for example, shading out other plants or using water and nutrients liberally to the detriment of neighboring plants. However, in an agricultural setting, the plants don't need such competitive measures.

"Our crop plants reflect many millions of years of evolution in the wild under these competitive conditions," said U. of I. plant biology professor Stephen P. Long, also a co-author on the study. "In a crop field we want plants to share resources and conserve water and nutrients, so we have been looking at what leaf arrangements would best do this."

The researchers aimed for three specific areas of improvement. First, productivity. Second, water usage. Third, combating climate change by reflecting more sunlight off the leaves. To address all three, they used the unique tactic of computationally modeling the whole soybean plant.

"Our approach used a technique called 'numerical optimization' to try out a very large number of combinations of structural traits to see which combination produced the best results with respect to each of our three goals," said lead author Darren Drewry, a former postdoctoral researcher who is now at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory at the California Institute of Technology. "And surprisingly, there are combinations of these traits that can improve each of these goals at the same time."

The model looks at biological functions, such as photosynthesis and water use, as well as the physical environment. The researchers looked at how the plant's biology changed with varying structural traits such as leaf area distributions, how the leaves are arranged vertically on the stalk, and the angles of the leaves.

For example, by changing the structure so that leaves are more evenly distributed, more light can penetrate through the canopy. This lets photosynthesis happen on multiple levels, instead of being limited to the top, thus increasing the plant's bean-producing power. A less dense canopy uses less water without affecting productivity. And changing the angle of the leaves can let the plant reflect back more solar radiation to offset climate change.

"Most of the genetic approaches have looked at very specific traits," Kumar said. "They haven't looked at restructuring the whole canopy. We have a very unique modeling capability where we can model the entire plant canopy in a lot of detail. We can also model what these plant canopies can do in a future climate, so that it will still be valid 40 or 50 years down the line."

Once the computer predicts an optimal plant structure, then the crop can be selected or bred from the diverse forms of soybeans that are already available – without the regulation and costs associated with genetic engineering.

"This kind of numerical approach – using realistic models of plant canopies – can provide a method for trying many more trait combinations than are possible through field breeding," Drewry said. "This approach then can help guide field programs by pointing to plants with particular combinations of traits, already tested in the computer, which may have the biggest payoff in the field."

The researchers hope their modeling approach will not only improve soybean yields, but also benefit agriculture worldwide as the population continues to rise.

According to Long, "The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations predict that by 2050 we will need 70 percent more primary foodstuffs to feed the world than we are producing today – and yet will have to do that with probably no more water while at the same time dealing with climate change."

"We need new innovations to achieve the yield jump," Long said. "We've shown that by altering leaf arrangement we could have a yield increase, without using more water and also providing an offset to global warming."

Next, the researchers plan to use their model to analyze other crops for their structural traits. As part of a project supported by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, Long is leading an international effort to improve rice, soybean and cassava guided by similar computational approaches, with the end goal of making more productive and sustainable crops.

"By examining plants using detailed computer models and optimization, we have the potential to greatly expedite the development of new types of agricultural plants that can tackle some of the greatest challenges facing society today, related to the need to produce more food in a more variable and uncertain climate system," Drewry said.

INFORMATION:

Kumar also is affiliated with the department of atmospheric sciences. Long also is a professor of crop sciences and a faculty member in the Institute for Genomic Biology. The National Science Foundation and the Gates foundation supported this work.

Editor's note: To reach Praveen Kumar, call 217-333-4688; email kumar1@illinois.edu.

To reach Stephen P. Long, email slong@illinois.edu.

The paper, "Simultaneous Improvement in Productivity, Water Use and Albedo Through Crop Structural Modification," is available online at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/gcb.12567/full.

Scientists say new computer model amounts to a lot more than a hill of beans

2014-04-03

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Dress and behavior of mass shooters as factors to predict and prevent future attacks

2014-04-03

New Rochelle, NY, April 3, 2014–In many recent incidents of premeditated mass shooting the perpetrators have been male and dressed in black, and may share other characteristics that could be used to identify potential shooters before they commit acts of mass violence. Risk factors related to the antihero, dark-knight persona adopted by these individuals are explored in an article in Violence and Gender, a new peer-reviewed journal from Mary Ann Liebert, Inc., publishers. The article is available free on the Violence and Gender website at http://www.liebertpub.com/vio.

In ...

Ouch! Computer system spots fake expressions of pain better than people

2014-04-03

BUFFALO, N.Y. — A joint study by researchers at the University of California, San Diego, the University at Buffalo, and the University of Toronto has found that a computer–vision system can distinguish between real or faked expressions of pain more accurately than can humans.

This ability has obvious uses for uncovering pain malingering — fabricating or exaggerating the symptoms of pain for a variety of motives — but the system also could be used to detect deceptive actions in the realms of security, psychopathology, job screening, medicine and law.

The study, "Automatic ...

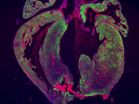

New study casts doubt on heart regeneration in mammals

2014-04-03

The mammalian heart has generally been considered to lack the ability to repair itself after injury, but a 2011 study in newborn mice challenged this view, providing evidence for complete regeneration after resection of 10% of the apex, the lowest part of the heart. In a study published by Cell Press in Stem Cell Reports on April 3, 2014, researchers attempted to replicate these recent findings but failed to uncover any evidence of complete heart regeneration in newborn mice that underwent apex resection.

"Our results question the usefulness of the apex resection model ...

Hummingbirds' 22-million-year-old history of remarkable change is far from complete

2014-04-03

The first comprehensive map of hummingbirds' 22-million-year-old family tree—reconstructed based on careful analysis of 284 of the world's 338 known species—tells a story of rapid and ongoing diversification. The decade-long study reported in the Cell Press journal Current Biology on April 3 also helps to explain how today's hummingbirds came to live where they do.

Part of the secret to the birds' remarkable success lies in the formation of nine principal groups or clades, hummingbirds' unique relationship to flowering plants, and the birds' continued spread into new ...

Lactase persistence alleles reveal ancestry of southern African Khoe pastoralists

2014-04-03

In a new study a team of researchers lead from Uppsala University show how lactase persistence variants tell the story about the ancestry of the Khoe people in southern Africa. The team concludes that pastoralist practices were brought to southern Africa by a small group of migrants from eastern Africa. The study is published in Current Biology today.

"This is really an exciting time for African genetics. Up until now, routes of human migration in Africa were inferred mostly based on linguistics and archaeology, now we can use genetics to test these hypotheses." says ...

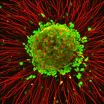

Cancer and the Goldilocks effect

2014-04-03

Researchers at the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine have found that too little or too much of an enzyme called SRPK1 promotes cancer by disrupting a regulatory event critical for many fundamental cellular processes, including proliferation.

The findings are published in the current online issue of Molecular Cell.

The family of SRPK kinases was first discovered by Xiang-Dong Fu, PhD, professor in the Department of Cellular and Molecular Medicine at UC San Diego in 1994. In 2012, Fu and colleagues uncovered that SPRK1 was a key signal transducer ...

Study helps unravel the tangled origin of ALS

2014-04-03

MADISON, Wis. — By studying nerve cells that originated in patients with a severe neurological disease, a University of Wisconsin-Madison researcher has pinpointed an error in protein formation that could be the root of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

Also called Lou Gehrig's disease, ALS causes paralysis and death. According to the ALS Association, as many as 30,000 Americans are living with ALS.

After a genetic mutation was discovered in a small group of ALS patients, scientists transferred that gene to animals and began to search for drugs that might treat those ...

Patient stem cells help identify common problem in ALS

2014-04-03

Harvard stem cell scientists have discovered that a recently approved medication for epilepsy may possibly be a meaningful treatment for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)—Lou Gehrig's disease, a uniformly fatal neurodegenerative disorder. The researchers are now collaborating with Massachusetts General Hospital to design an initial clinical trial testing the safety of the treatment in ALS patients.

The investigators all caution that a great deal needs to be done to assure the safety and efficacy of the treatment in ALS patients, before physicians should start offering ...

Tumor suppressor gene TP53 mutated in 90 percent of most common childhood bone tumor

2014-04-03

(MEMPHIS, Tenn. – April 3, 2014) – The St. Jude Children's Research Hospital—Washington University Pediatric Cancer Genome Project found mutations in the tumor suppressor gene TP53 in 90 percent of osteosarcomas, suggesting the alteration plays a key role early in development of the bone cancer. The research was published today online ahead of print in the journal Cell Reports.

The discovery that TP53 is altered in nearly every osteosarcoma also helps to explain a long-standing paradox in osteosarcoma treatment, which is why at standard doses radiation therapy is largely ...

ER doctors commonly miss more strokes among women, minorities and younger patients

2014-04-03

Analyzing federal health care data, a team of researchers led by a Johns Hopkins specialist concluded that doctors overlook or discount the early signs of potentially disabling strokes in tens of thousands of American each year, a large number of them visitors to emergency rooms complaining of dizziness or headaches.

The findings from the medical records review, reported online April 3 in the journal Diagnosis, show that women, minorities and people under the age of 45 who have these symptoms of stroke were significantly more likely to be misdiagnosed in the week prior ...