(Press-News.org) MADISON, Wis. — By studying nerve cells that originated in patients with a severe neurological disease, a University of Wisconsin-Madison researcher has pinpointed an error in protein formation that could be the root of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

Also called Lou Gehrig's disease, ALS causes paralysis and death. According to the ALS Association, as many as 30,000 Americans are living with ALS.

After a genetic mutation was discovered in a small group of ALS patients, scientists transferred that gene to animals and began to search for drugs that might treat those animals. But that approach has yet to work, says Su-Chun Zhang, a neuroscientist at the Waisman Center at UW-Madison, who is senior author of the new report, published April 3 in the journal Cell Stem Cell.

Zhang has been using a different approach — studying diseased human cells in lab dishes. Those cells, called motor neurons, direct muscles to contract and are the site of failure in ALS.

About 10 years ago, Zhang was the first in the world to grow motor neurons from human embryonic stem cells. More recently, he updated that approach by transforming skin cells into iPS (induced pluripotent stem) cells that were transformed, in turn, into motor neurons.

IPS cells can be used as "disease models," as they carry many of the same traits as their donor. Zhang says the iPS approach offers a key advantage over the genetic approach, which "can only study the results of a known disease-causing gene. With iPS, you can take a cell from any patient, and grow up motor neurons that have ALS. That offers a new way to look at the basic disease pathology."

In the new report, Zhang, Waisman scientist Hong Chen, and colleagues have pointed a finger at proteins that build a transport structure inside the motor neurons. Called neurofilament, this structure moves chemicals and cellular subunits to the far reaches of the nerve cell. The cargo needing movement includes neurotransmitters, which signal the muscles, and mitochondria, which process energy.

Motor neurons that control foot muscles are about three feet long, so neurotransmitters must be moved a yard from their origin in the cell body to the location where they can signal the muscles, Zhang says. A patient lacking this connection becomes paralyzed; tellingly, the first sign of ALS is often paralysis in the feet and legs.

Scientists have known for some time that in ALS, "tangles" along the nerve's projections, formed of misshapen protein, block the passage along the nerve fibers, eventually causing the nerve fiber to malfunction and die. The core of the new discovery is the source of these tangles: a shortage of one of the three proteins in the neurofilament.

The neurofilament combines structural and functional roles, Zhang says. "Like the studs, joists and rafters of a house, the neurofilament is the backbone of the cell, but it's constantly changing. These proteins need to be shipped from the cell body, where they are produced, to the most distant part, and then be shipped back for recycling. If the proteins cannot form correctly and be transported easily, they form tangles that cause a cascade of problems."

Finding neurofilament tangles in an autopsy of an ALS patient "will not tell you how they happen, when or why they happen," Zhang says. But with millions of cells — all carrying the human disease — to work with, Zhang's research group discovered the source of the tangles in the protein subunits that compose the neurofilaments. "Our discovery here is that the disease ALS is caused by misregulation of one step in the production of the neurofilament," he says.

Beyond ALS, Zhang says "very similar tangles" appear in Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases. "We got really excited at the idea that when you study ALS, you may be looking at the root of many neurodegenerative disorders."

While working with motor neurons sourced in stem cells from patients, Zhang says he and his colleagues saw "quite an amazing thing. The motor neurons we reprogrammed from patient skin cells were relatively young, and we found that the misregulation happens very early, which means it is the most likely cause of this disease. Nobody knew this before, but we think if you can target this early step in pathology, you can potentially rescue the nerve cell."

In the experiment just reported, Zhang found a way to rescue the neural cells living in his lab dishes. When his group "edited" the gene that directs formation of the deficient protein, "suddenly the cells looked normal," Zhang says.

Already, he reports, scientists at the Small Molecule Screening and Synthesis Facility at UW-Madison are looking for a way to rescue diseased motor neurons. These neurons are made by the millions from stem cells using techniques that Zhang has perfected over the years.

Zhang says "libraries" of candidate drugs, each containing a thousand or more compounds, are being tested. "This is exciting. We can put this into action right away. The basic research is now starting to pay off. With a disease like this, there is no time to waste."

INFORMATION:

—David Tenenbaum, 608-265-8549, djtenenb@wisc.edu

Study helps unravel the tangled origin of ALS

2014-04-03

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Patient stem cells help identify common problem in ALS

2014-04-03

Harvard stem cell scientists have discovered that a recently approved medication for epilepsy may possibly be a meaningful treatment for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)—Lou Gehrig's disease, a uniformly fatal neurodegenerative disorder. The researchers are now collaborating with Massachusetts General Hospital to design an initial clinical trial testing the safety of the treatment in ALS patients.

The investigators all caution that a great deal needs to be done to assure the safety and efficacy of the treatment in ALS patients, before physicians should start offering ...

Tumor suppressor gene TP53 mutated in 90 percent of most common childhood bone tumor

2014-04-03

(MEMPHIS, Tenn. – April 3, 2014) – The St. Jude Children's Research Hospital—Washington University Pediatric Cancer Genome Project found mutations in the tumor suppressor gene TP53 in 90 percent of osteosarcomas, suggesting the alteration plays a key role early in development of the bone cancer. The research was published today online ahead of print in the journal Cell Reports.

The discovery that TP53 is altered in nearly every osteosarcoma also helps to explain a long-standing paradox in osteosarcoma treatment, which is why at standard doses radiation therapy is largely ...

ER doctors commonly miss more strokes among women, minorities and younger patients

2014-04-03

Analyzing federal health care data, a team of researchers led by a Johns Hopkins specialist concluded that doctors overlook or discount the early signs of potentially disabling strokes in tens of thousands of American each year, a large number of them visitors to emergency rooms complaining of dizziness or headaches.

The findings from the medical records review, reported online April 3 in the journal Diagnosis, show that women, minorities and people under the age of 45 who have these symptoms of stroke were significantly more likely to be misdiagnosed in the week prior ...

Jamming a protein signal forces cancer cells to devour themselves

2014-04-03

HOUSTON -- Under stress from chemotherapy or radiation, some cancer cells dodge death by consuming a bit of themselves, allowing them to essentially sleep through treatment and later awaken as tougher, resistant disease.

Interfering with a single cancer-promoting protein and its receptor can turn this resistance mechanism into lethal, runaway self-cannibalization, researchers at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center report in the journal Cell Reports.

"Prolactin is a potent growth factor for many types of cancers, including ovarian cancer," said senior author ...

Dopamine and hippocampus

2014-04-03

Montreal, April 3, 2014 – Bruno Giros, PhD, a researcher at the Douglas Mental Health University Institute and a professor in the Department of Psychiatry at McGill University, has demonstrated, for the first time, the role that dopamine plays in a region of the brain called the hippocampus. Published in Biological Psychiatry, this discovery opens the door to a better understanding of psychiatric diseases, such as schizophrenia.

Dopamine is a neurotransmitter that plays a central role in brain function, and many mental illnesses involve an imbalance in this chemical. ...

A once-only cataclysmic event and other mysteries of earth's crust and upper mantle

2014-04-03

Boulder, Colo., USA - The April 2014 Lithosphere is now available in print. Locations covered include the Acatlán Complex, Mexico; east Yilgarn craton, Australia; the eastern Paganzo basin, Argentina; the hotspot-related Yellowstone crescent, USA; and the western Alps. Locations investigated in four new papers published online on 2 April include the Banks Island assemblage in Alaska and British Columbia; The Diligencia basin of the Orocopia Mountains in California; a U.S. post-Grenville large igneous province; and South Island, New Zealand.

Abstracts are online at http://lithosphere.gsapubs.org/content/early/recent. ...

Energy breakthrough uses sun to create solar energy materials

2014-04-03

CORVALLIS, Ore. – In a recent advance in solar energy, researchers have discovered a way to tap the sun not only as a source of power, but also to directly produce the solar energy materials that make this possible.

This breakthrough by chemical engineers at Oregon State University could soon reduce the cost of solar energy, speed production processes, use environmentally benign materials, and make the sun almost a "one-stop shop" that produces both the materials for solar devices and the eternal energy to power them.

The findings were just published in RSC Advances, ...

New tweetment: Twitter users describe real-time migraine agony

2014-04-03

ANN ARBOR—Someone's drilling an icicle into your temple, you're throwing up, and light and sound are unbearable.

Yes, it's another migraine attack. But now in 140 characters on Twitter, you can share your agony with other sufferers. It indicates a trend toward the cathartic sharing of physical pain, as well as emotional pain on social media.

"As technology and language evolve, so does the way we share our suffering," said principal investigator Alexandre DaSilva, assistant professor and director of the Headache and Orofacial Pain Effort at University of Michigan School ...

Indigenous societies' 'first contact' typically brings collapse, but rebounds are possible

2014-04-03

It was disastrous when Europeans first arrived in what would become Brazil -- 95 percent of its population, the majority of its tribes, and essentially all of its urban and agricultural infrastructure vanished. The experiences of Brazil's indigenous societies mirror those of other indigenous peoples following "first contact."

A new study of Brazil's indigenous societies led by Santa Fe Institute researcher Marcus Hamilton paints a grim picture of their experiences, but also offers a glimmer of hope to those seeking ways to preserve indigenous societies.

Even among ...

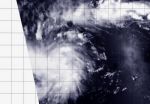

NASA's Aqua satellite flies over newborn Tropical Depression 05W

2014-04-03

The fifth tropical depression of the northwestern Pacific Ocean tropical cyclone season formed far from land as NASA's Aqua satellite passed overhead and captured a visible image of the storm on April 4.

NASA's Aqua satellite passed over newborn Tropical Depression 05W on April 3 at 03:10 UTC/April 2 at 11:10 p.m. EDT. The Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer or MODIS instrument captured a visible picture of the storm, revealing good circulation and strong convection and thunderstorms around the center of circulation.

The Joint Typhoon Warning Center or JTWC ...