(Press-News.org) COLUMBIA, Mo. – The Cambrian Period is a time when most phyla of marine invertebrates first appeared in the fossil record. Also dubbed the "Cambrian explosion," fossilized records from this time provide glimpses into evolutionary biology when the world's ecosystems rapidly changed and diversified. Most fossils show the organisms' skeletal structure, which may or may not give researchers accurate pictures of these prehistoric organisms. Now, researchers at the University of Missouri have found rare, fossilized embryos they believe were undiscovered previously. Their methods of study may help with future interpretation of evolutionary history.

"Before the Ediacaran and Cambrian Periods, organisms were unicellular and simple," said James Schiffbauer, assistant professor of geological sciences in the MU College of Arts and Science. "The Cambrian Period, which occurred between 540 million and 485 million years ago, ushered in the advent of shells. Over time, shells and exoskeletons can be fossilized, giving scientists clues into how organisms existed millions of years ago. This adaptation provided protection and structural integrity for organisms. My work focuses on those harder-to-find, soft-tissue organisms that weren't preserved quite as easily and aren't quite as plentiful."

Schiffbauer and his team, including Jesse Broce, a Huggins Scholar doctoral student in the Department of Geological Sciences at MU, now are studying fossilized embryos in rocks that provide rare opportunities to study the origins and developmental biology of early animals during the Cambrian explosion.

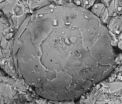

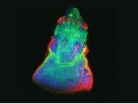

Broce collected fossils from the lower Cambrian Shuijingtuo Formation in the Hubei Province of South China and analyzed samples to determine the chemical makeup of the rocks. Soft tissue fossils have different chemical patterns than harder, skeletal remains, helping researchers identify the processes that contributed to their preservation. It is important to understand how the fossils were preserved, because their chemical makeups can also offer clues about the nature of the organisms' original tissues, Schiffbauer said.

"Something obviously went wrong in these fossils," Schiffbauer said. "Our Earth has a pretty good way of cleaning up after things die. Here, the cells' self-destructive mechanisms didn't happen, and these soft tissues could be preserved. While studying the fossils we collected, we found over 140 spherically shaped fossils, some of which include features that are reminiscent of division stage embryos, essentially frozen in time."

The fossilized embryos the researchers found were significantly smaller than other fossil embryos from the same time period, suggesting they represent a yet undescribed organism. Additional research will focus on identifying the parents of these embryos, and their evolutionary position.

Schiffbauer and his colleagues published this and related research in a volume of the Journal of Paleontology which he co-edited. The special issue, published by the Paleontological Society, includes several papers that analyze fossil evidence collected worldwide and includes integrated research focusing on this time frame, the Ediacaran–Cambrian transition. Schiffbauer and Broce's research, "Possible animal embryos form the lower Cambrian Shuijingtuo Formation, Hubei Province, South China," was funded by the National Science Foundation.

INFORMATION:

Editor's Note: For more information on the special issue of the Journal of Paleontology please visit the Mizzou Paleobiology Website at paleo.missour.edu.

MU researchers find rare fossilized embryos more than 500 million years old

Study methods may help with future interpretation of evolutionary history

2014-04-10

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Gutting of campaign finance laws enhances influence of corporations and wealthy Americans

2014-04-10

PRINCETON, N.J.—Affluent individuals and business corporations already have vastly more influence on federal government policy than average citizens, according to recently released research by Princeton University and Northwestern University. This research suggests that the Supreme Court's continuing attack on campaign finance laws is further increasing the political clout of business firms and the wealthy.

Martin Gilens, professor of politics at Princeton, and Benjamin I. Page, Gordon Scott Fulcher Professor of Decision Making, of Northwestern University used a unique ...

Pseudo-mathematics and financial charlatanism

2014-04-10

Providence, RI---Your financial advisor calls you up to suggest a new

investment scheme. Drawing on 20 years of data, he has set his

computer to work on this question: If you had invested according to

this scheme in the past, which portfolio would have been the best?

His computer assembled thousands of such simulated portfolios and

calculated for each one an industry-standard measure of return on

risk. Out of this gargantuan calculation, your advisor has chosen the

optimal portfolio. After briefly reminding you of the oft-repeated

slogan that "past performance ...

Name of new weakly electric fish species reflects hope for peace in Central Africa

2014-04-10

Two new species of weakly electric fishes from the Congo River basin are described in the open access journal ZooKeys. One of them, known from only a single specimen, is named "Petrocephalus boboto." "Boboto" is the word for peace in the Lingala language, the lingua franca of the Congo River, reflecting the authors' hope for peace in troubled Central Africa.

On a 2010 field trip to the Congo River of Democratic Republic of the Congo, in the riverside village of Yangambi-Lokélé, French ichthyologist Sébastien Lavoué of the Taiwan Institute of Oceanography and American ...

Planaria deploy an ancient gene expression program in the course of organ regeneration

2014-04-10

KANSAS CITY, MO - As multicellular creatures go, planaria worms are hardly glamorous. To say they appear rudimentary is more like it. These tiny aquatic flatworms that troll ponds and standing water resemble brown tubes equipped with just the basics: a pair of beady light-sensing "eyespots" on their head and a feeding tube called the pharynx (which doubles as the excretory tract) that protrudes from a belly sac to suck up food. It's hard to feel kinship with them.

But admiration is another thing, because many planaria species regenerate in wondrous ways—namely, when ...

Scarless wound healing -- applying lessons learned from fetal stem cells

2014-04-10

New Rochelle, NY, April 10, 2014—In early fetal development, skin wounds undergo regeneration and healing without scar formation. This mechanism of wound healing later disappears, but by studying the fetal stem cells capable of this scarless wound healing, researchers may be able to apply these mechanisms to develop cell-based approaches able to minimize scarring in adult wounds, as described in a Critical Review article published in Advances in Wound Care, a monthly publication from Mary Ann Liebert, Inc., publishers and an Official Journal of the Wound Healing Society. ...

Therapeutic options and bladder-preserving strategies in bladder cancer

2014-04-10

New Rochelle, NY, April 10, 2014—Men are three to four times more likely to get bladder cancer than women. The possible causes for this greater risk among men, the importance of early and accurate diagnosis, and the scope of available and emerging surgical, chemotherapeutic, and immunotherapeutic approaches for treating bladder cancer in men are the focus of a comprehensive Review article in Journal of Men's Health, a peer-reviewed publication from Mary Ann Liebert, Inc., publishers. The article is available free on the Journal of Men's Health website.

Coauthors R. ...

Camels emit less methane than cows or sheep

2014-04-10

Ruminant cows and sheep account for a major proportion of the methane produced around the world. Currently around 20 percent of global methane emissions stem from ruminants. In the atmosphere methane contributes to the greenhouse effect – that's why researchers are looking for ways of reducing methane production by ruminants. Comparatively little is known about the methane production of other animal species – but one thing seems to be clear: Ruminants produce more of the gas per amount of converted feed than other herbivores.

The only other animal group that regularly ...

Neurofinance study confirms that financial decisions are made on an emotional basis

2014-04-10

The willingness of decision makers to take risks increases when they play games of chance with money won earlier. Risk taking also rises when they have the opportunity to compensate for earlier losses by breaking even. This outcome was demonstrated by Dr. Kaisa Hytönen, a Finnish Aalto University researcher in neurofinance, together with her international colleagues.

There are frequently various linkages between financial decisions: the circumstances accompanying the decision are rarely completely independent of each other. Both profits and losses, for example, on the ...

HIV battle must focus on hard-hit streets, paper argues

2014-04-10

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — In U.S. cities, it's not just what you do, but also your address that can determine whether you will get HIV and whether you will survive. A new paper in the American Journal of Public Health illustrates the effects of that geographic disparity – which tracks closely with race and poverty – and calls for an increase in geographically targeted prevention and treatment efforts.

"People of color are disproportionately impacted, and their risk of infection is a function not just of behavior but of where they live and the testing and treatment ...

Obsessive-compulsive disorder may reflect a propensity for bad habits

2014-04-10

Philadelphia, PA, April 10, 2014 – Two new studies published this week in Biological Psychiatry shed light on the propensity for habit formation in obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). These studies suggest that a tendency to develop habits, i.e., the compulsive component of the disorder, may be a core feature of the disorder rather than a consequence of irrational beliefs. In other words, instead of washing one's hands because of the belief that they are contaminated, some people may develop concerns about hand contamination as a consequence of a recurring urge to wash ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Vision sensing for intelligent driving: technical challenges and innovative solutions

To attempt world record, researchers will use their finding that prep phase is most vital to accurate three-point shooting

AI is homogenizing human expression and thought, computer scientists and psychologists say

Severe COVID-19, flu facilitate lung cancer months or years later, new research shows

Housing displacement, employment disruption, and mental health after the 2023 Maui wildfires

GLP-1 receptor agonist use and survival among patients with type 2 diabetes and brain metastases

Solid but fluid: New materials reconfigure their entire crystal structure in response to humidity

New research reveals how development and sex shape the brain

New discovery may improve kidney disease diagnosis in black patients

What changes happen in the aging brain?

Pew awards fellowships to seven scientists advancing marine conservation

Turning cancer’s protein machinery against itself to boost immunity

Current Pharmaceutical Analysis releases Volume 22, Issue 2 with open access research

Researchers capture thermal fluctuations in polymer segments for the first time

16-year study finds major health burden in single‑ventricle heart

Disposable vapes ban could lead young adults to switch to cigarettes, study finds

Adults with concurrent hearing and vision loss report barriers and challenges in navigating complex, everyday environments

Breast cancer stage at diagnosis differs sharply across rural US regions

Concrete sensor manufacturer Wavelogix receives $500,000 grant from National Science Foundation

California communities’ recovery time between wildfire smoke events is shrinking

Augmented reality job coaching boosts performance by 79% for people with disabilities

Medical debt associated with deferring dental, medical, and mental health care

AAI appoints Anand Balasubramani as Chief Scientific Programs Officer

Prior authorization may hinder access to lifesaving heart failure medications

Scholars propose transparency, credit and accountability as key principles in scientific authorship guidelines

Jeonbuk National University researchers develop DDINet for accurate and scalable drug-drug interaction prediction

IEEE researchers achieve 20x signal boost in cerebral blood flow monitoring with next-generation interferometric diffusing wave spectroscopy

IEEE researchers achieve low-power ultrashort mid-IR pulse compression

Deep-sea natural compound targets cancer cells through a dual mechanism

Antibiotics can affect the gut microbiome for several years

[Press-News.org] MU researchers find rare fossilized embryos more than 500 million years oldStudy methods may help with future interpretation of evolutionary history