(Press-News.org) This news release is available in Spanish.

Until now, the carbon 14 technique, a radioactive isotope which gradually disappears with the passing of time, has been used to date prehistoric remains. When about 40,000 years, in other words approximately the period corresponding to the arrival of the first humans in Europe, have elapsed, the portion that remains is so small that it can become easily contaminated and cause the dates to appear more recent. It was from 2005 onwards that a new technique began to be used; it is the one used to purify the collagen in DNA tests. Using this method, the portion of the original organic material is obtained and all the subsequent contamination is removed.

And by using this technique, scientists have been arriving at the same conclusions at key sites across Europe: "We can see that the arrival of our species in Europe took place 8,000 years earlier than what had been thought and we can see the earliest datings of our species and the most recent Neanderthal ones, in which, in a specific regional framework, there is no overlapping," explained Alvaro Arrizabalaga, professor of the department of Geography, Prehistory and Archaeology, and one of the UPV/EHU researchers alongside María-José Iriarte and Aritza Villaluenga.

The three caves chosen for the recently published research are located in Girona (L'Arbreda), Gipuzkoa (Labeko Koba) and Asturias (La Viña); in other words, at the westernmost and easternmost tips of the Pyrenees and it was where the flow of populations and animals between the peninsula and continent took place. "L'Arbreda is on the eastern pass; Labeko Koba, in the Deba valley, is located on the entry corridor through the Western Pyrenees (Arrizabalaga and Iriarte excavated it in a hurry in 1988 before it was destroyed by the building of the Arrasate-Mondragon bypass) and La Viña is of value as a paradigm, since it provides a magnificent sequence of the Upper Palaeolithic, in other words, of the technical and cultural behaviour of the Cro-magnons during the last glaciation", pointed out Arrizabalaga.

The selecting of the remains was very strict allowing only tools made of bones or, in the absence of them, bones bearing clear traces of human activity, as a general rule with butchery marks, in other words, cuts in the areas of the tendons so that the muscle could be removed. "The Labeko Koba curve is the most consistent of the three, which in turn are the most consistent on the Iberian Peninsula," explained Arrizabalaga. 18 remains were dated at Labeko Koba and the results are totally convergent with respect to their stratigraphic position, in other words, those that appeared at the lowest depths are the oldest ones.

The main conclusion –"the scene of the meeting between a Neanderthal and a Cro-magnon does not seem to have taken place on the Iberian Peninsula"– is the same as the one that has been gradually reached over the last three years by different research groups when studying key settlements in Great Britain, Italy, Germany and France. "For 25 years we had been saying that Neanderthals and early humans lived together for 8,000-10,000 years. Today, we think that in Europe there was a gap between one species and the other and, therefore, there was no hybridation, which did in fact take place in areas of the Middle East," explained Arrizabalaga. The UPV/EHU professor is also the co-author of a piece of research published in 2012 that puts back the datings of the Neanderthals. "We did the dating again in accordance with the ultrafiltration treatment that eliminates rejuvenating contamination, remains of the Mousterian, the material culture belonging to the Neanderthals from sites in the south of the Peninsula. Very recent dates had been obtained in them –up to 29,000 years– but the new datings go back to 44,000 years older than the first dates that can be attributed to the Cro-Magnons," explained the UPV/EHU professor.

INFORMATION: END

Neanderthals and Cro-magnons did not coincide on the Iberian Peninsula

Neanderthals and Cro-magnons did not coincide on the Iberian Peninsula

2014-04-14

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

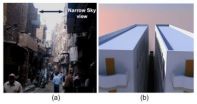

Let the sun shine in: Redirecting sunlight to urban alleyways

2014-04-14

WASHINGTON, April 14—In dense, urban centers around the world, many people live and work in dim and narrow streets surrounded by tall buildings that block sunlight. And as the global population continues to rise and buildings are jammed closer together, the darkness will only spread.

To alleviate the problem, Egyptian researchers have developed a corrugated, translucent panel that redirects sunlight onto narrow streets and alleyways. The panel is mounted on rooftops and hung over the edge at an angle, where it spreads sunlight onto the street below. The researchers describe ...

Wolves at the door: Study finds recent wolf-dog hybridization in Caucasus region

2014-04-14

Dog owners in the Caucasus Mountains of Georgia might want to consider penning up their dogs more often: hybridization of wolves with shepherd dogs might be more common, and more recent, than previously thought, according to a recently published study in the Journal of Heredity (DOI: 10.1093/jhered/esu014).

Dr. Natia Kopaliani, Dr. David Tarkhnishvili, and colleagues from the Institute of Ecology at Ilia State University in Georgia and from the Tbilisi Zoo in Georgia used a range of genetic techniques to extract and examine DNA taken from wolf and dog fur samples as well ...

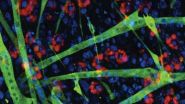

Regenerating muscle in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: Age matters

2014-04-14

LA JOLLA, Calif., April 11, 2014 — A team of scientists led by Pier Lorenzo Puri, M.D., associate professor at Sanford-Burnham Medical Research Institute (Sanford-Burnham), in collaboration with Fondazione Santa Lucia in Rome, Italy, have published details of how a class of drugs called "HDACis" drive muscle-cell regeneration in the early stages of dystrophic muscles, but fail to work in late stages. The findings are key to furthering clinical development of HDACis for Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), an incurable muscle-wasting disease.

A symphony to rebuild muscle

The ...

New 'tunable' semiconductors will allow better detectors, solar cells

2014-04-14

One of the great problems in physics is the detection of electromagnetic radiation – that is, light – which lies outside the small range of wavelengths that the human eye can see. Think X-rays, for example, or radio waves.

Now, researchers have discovered a way to use existing semiconductors to detect a far wider range of light than is now possible, well into the infrared range. The team hopes to use the technology in detectors, obviously, but also in improved solar cells that could absorb infrared light as well as the sun's visible rays.

"This technology will also ...

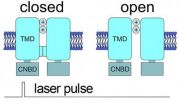

A stable model for an unstable target

2014-04-14

A study in The Journal of General Physiology provides new insights about singlet oxygen and sets the stage for better understanding of this highly reactive and challenging substance.

Singlet oxygen is an electronically excited state of oxygen that is less stable than normal oxygen. Its high reactivity has enabled its use in photodynamic therapy, in which light is used in combination with a photosensitizing drug to generate large amounts of singlet oxygen to kill cancer cells or various pathogens.

Light-generated singlet oxygen also plays a role in a range of biological ...

Better solar cells, better LED light and vast optical possibilities

2014-04-14

Changes at the atom level in nanowires offer vast possibilities for improvement of solar cells and LED light. NTNU-researchers have discovered that by tuning a small strain on single nanowires they can become more effective in LEDs and solar cells.

NTNU researchers Dheeraj Dasa and Helge Weman have, in cooperation with IBM, discovered that gallium arsenide can be tuned with a small strain to function efficiently as a single light-emitting diode or a photodetector. This is facilitated by the special hexagonal crystal structure, referred to as wurtzite, which the NTNU ...

Pioneering findings on the dual role of carbon dioxide in photosynthesis

2014-04-14

Scientists at Umeå University in Sweden have found that carbon dioxide, in its ionic form bicarbonate, has a regulating function in the splitting of water in photosynthesis. This means that carbon dioxide has an additional role to being reduced to sugar. The pioneering work is published in the latest issue of the scientific journal PNAS.

It is well known that inorganic carbon in the form of carbon dioxide, CO2, is reduced in a light driven process known as photosynthesis to organic compounds in the chloroplasts. Less well known is that inorganic carbon also affects the ...

The result of slow degradation

2014-04-14

This news release is available in German. Although persistent environmental pollutants have been and continue to be released worldwide, the Arctic and Antarctic regions are significantly more contaminated than elsewhere. The marine animals living there have some of the highest levels of persistent organic pollutant (POP) contamination of any creatures. The Inuit people of the Arctic, who rely on a diet of fish, seals and whales, have also been shown to have higher POP concentrations than people living in our latitudes.

Today, the production and use of nearly two dozen ...

Nutrient-rich forests absorb more carbon

2014-04-14

The ability of forests to sequester carbon from the atmosphere depends on nutrients available in the forest soils, shows new research from an international team of researchers including the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA).

The study showed that forests growing in fertile soils with ample nutrients are able to sequester about 30% of the carbon that they take up during photosynthesis. In contrast, forests growing in nutrient-poor soils may retain only 6% of that carbon. The rest is returned to the atmosphere as respiration.

"This paper produces ...

Scientists open door to better solar cells, superconductors and hard-drives

2014-04-14

Using DESY's bright research light sources, scientists have opened a new door to better solar cells, novel superconductors and smaller hard-drives. The research reported in the scientific journal Nature Communications this week enhances the understanding of the interface of two materials, where completely new properties can arise. With their work, the team of Prof. Andrivo Rusydi from the National University of Singapore and Prof. Michael Rübhausen from the Hamburg Center for Free-Electron Laser Science (CFEL) have solved a long standing mystery in the physics of condensed ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Kidney cancer study finds belzutifan plus pembrolizumab post-surgery helps patients at high risk for relapse stay cancer-free longer

Alkali cation effects in electrochemical carbon dioxide reduction

Test platforms for charging wireless cars now fit on a bench

$3 million NIH grant funds national study of Medicare Advantage’s benefit expansion into social supports

Amplified Sciences achieves CAP accreditation for cutting-edge diagnostic lab

Fred Hutch announces 12 recipients of the annual Harold M. Weintraub Graduate Student Award

Native forest litter helps rebuild soil life in post-mining landscapes

Mountain soils in arid regions may emit more greenhouse gas as climate shifts, new study finds

Pairing biochar with other soil amendments could unlock stronger gains in soil health

Why do we get a skip in our step when we’re happy? Thank dopamine

UC Irvine scientists uncover cellular mechanism behind muscle repair

Platform to map living brain noninvasively takes next big step

Stress-testing the Cascadia Subduction Zone reveals variability that could impact how earthquakes spread

We may be underestimating the true carbon cost of northern wildfires

Blood test predicts which bladder cancer patients may safely skip surgery

Kennesaw State's Vijay Anand honored as National Academy of Inventors Senior Member

Recovery from whaling reveals the role of age in Humpback reproduction

Can the canny tick help prevent disease like MS and cancer?

Newcomer children show lower rates of emergency department use for non‑urgent conditions, study finds

Cognitive and neuropsychiatric function in former American football players

From trash to climate tech: rubber gloves find new life as carbon capturers materials

A step towards needed treatments for hantaviruses in new molecular map

Boys are more motivated, while girls are more compassionate?

Study identifies opposing roles for IL6 and IL6R in long-term mortality

AI accurately spots medical disorder from privacy-conscious hand images

Transient Pauli blocking for broadband ultrafast optical switching

Political polarization can spur CO2 emissions, stymie climate action

Researchers develop new strategy for improving inverted perovskite solar cells

Yes! The role of YAP and CTGF as potential therapeutic targets for preventing severe liver disease

Pancreatic cancer may begin hiding from the immune system earlier than we thought

[Press-News.org] Neanderthals and Cro-magnons did not coincide on the Iberian PeninsulaNeanderthals and Cro-magnons did not coincide on the Iberian Peninsula