(Press-News.org) Cells in the brain called pericytes that have not been high on the list of targets for treating diseases like Alzheimer's may play a more crucial role in the development of neurodegenerative diseases than has been realized.

The findings, published Nov. 4 in Neuron, cast the pericyte in a surprising new role as a key player shaping blood flow in the brain and protecting sensitive brain tissue from harmful substances. By manipulating pericyte levels, scientists were able to re-create in the brains of mice an array of abnormalities that mirror in striking fashion the brain difficulties that occur in many people as they age.

"For 150 years these cells have been known to exist in the brain, but we haven't known exactly what they are doing in adults," said Berislav Zlokovic, M.D., Ph.D., the neuroscientist who led the research at the University of Rochester Medical Center. "It turns out that pericytes are very important for helping maintain a brain environment crucial to the health of neurons. The pericyte offers us an exciting new target for new treatments for neurodegenerative diseases."

While damage to neurons oftentimes causes the symptoms that patients experience – dementia in Alzheimer's, and movement difficulties in Parkinson's disease, for instance – neuroscientists know that neurons depend on a broad variety of factors coming together to create just the right environment to thrive. Zlokovic himself has pioneered the concept that impaired blood flow and flaws in the blood-brain barrier may play a huge role in the development of diseases like Alzheimer's through their impact on neurons.

In the most recent findings from Zlokovic's laboratory, the two first authors who contributed equally to the research, graduate student Robert Bell and M.D./Ph.D. student Ethan Winkler, teased out the role of the pericyte in the process. Pericytes ensheath the smallest blood vessels in the brain, wrapping around capillaries like ivy wrapping around a pipe and helping to maintain the structural integrity of the vessels.

It turns out that pericytes do much more. The team found that the cells are central to determining the amount of blood flowing in the brain and play an instrumental role in maintaining the barrier that stops toxic substances from leaking out of the capillaries and into brain tissue. When the team reduced the number of working pericytes in the brains of mice, the effects included reduced blood flow, greater exposure of brain tissue to toxic substances, impaired learning and memory, and damage to the neurons – all phenomena that are more likely to happen to people as they age.

"This work shows that other cells in the brain have a tremendous effect on the neurons, even driving the neurodegenerative process," said Winkler. "This is very exciting."

To make the finding, the team studied mice in which the normal number of pericytes is reduced dramatically. Scientists studied young mice (about one month old), middle-aged mice (about six to eight months old), and older mice (14 to 16 months old).

The amount of damage that occurred depended on age, with the worst damage occurring consistently in the oldest mice – a finding that parallels what happens with people, whose brains are much more likely to suffer neurodegenerative conditions like Alzheimer's or Parkinson's disease as they age. The mice experienced an array of problems that match up pretty closely with the brain abnormalities that people with neurodegenerative conditions like Alzheimer's experience.

Among the findings in mice with reduced levels of pericytes:

Cerebral blood flow was reduced, and the problem worsened as the mice got older. Older mice had 50 percent less blood flow than mice of similar age with a normal number of pericytes. Younger and middle-age mice had 23 percent less and 33 to 37 percent less blood flow, respectively.

Serum proteins and toxic molecules were much more likely to gain entry to the brain, thanks to a breakdown of the blood-brain barrier. For instance, molecules such as hemosiderin, fibrin, thrombin and plasmin are toxic in the brain and are normally not found in brain tissue. The older mice had 20 to 25 times as much accumulation of these toxins in their brain tissue as their normal counterparts; the younger and middle-age mice had three times as much and 8 to 10 times as much, respectively.

The breakdown in the blood-brain barrier was especially evident in blood vessel structures known as tight junctions, which play an important role in stopping harmful substances from reaching brain tissue. Their activity in the older mice was down 40 to 60 percent in older and middle-age mice compared to their normal counterparts.

Compared to normal mice, the mice with fewer pericytes had structural damage to their neurons, including loss of dendritic length and spine density. Again, the amount of damage correlated to the age of the mice, with older mice showing more damage. The team also documented impaired learning and memory in the middle-age and the older mice, but not the youngest mice.

"Our findings show that chronic vascular damage due to pericyte loss results in neurodegeneration," said Zlokovic, who is Dean's Professor in the Departments of Neurosurgery and Neurology and director of the Center for Neurodegenerative and Vascular Brain Disorders. "It may be that a vascular insult is common to many different types of neurodegenerative processes and may be significant in causing the symptoms seen in diseases such as Alzheimer's and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis."

The findings could cause neuroscientists to change their views of the origins of many neurodegenerative disorders, said Bell, who notes that a recently developed tool to track pericyte activity in the brain helped the team tackle the role of the pericyte.

"If all your tools are designed to study neurons, you'll learn a lot about neurons," Bell said. "We haven't known much about pericytes simply because we haven't had good tools to watch them. If you can't see the cells, you can't study them."

INFORMATION:

In addition to Bell, Winkler, and Zlokovic, other authors include Abhay Sagare, Ph.D., senior instructor; Rashid Deane, Ph.D., research professor; Itender Singh, Ph.D., postdoctoral research associate; and Barbra LaRue, technical associate. The project was funded by the National Institute on Aging (grant # R37AG023084) and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (grant # R37NS34467).

Zlokovic is the founder of and an equity holder in three companies exploring new treatments for stroke and neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer's: Socratech, ZZ Alztech, and ZZ Biotech. The University of Rochester holds an equity interest in all three companies as well.

The pericyte becomes a player in Alzheimer's, other diseases

2010-11-18

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Georgia Tech researchers design machine learning technique to improve consumer medical searches

2010-11-18

Medical websites like WebMD provide consumers with more access than ever before to comprehensive health and medical information, but the sites' utility becomes limited if users use unclear or unorthodox language to describe conditions in a site search. However, a group of Georgia Tech researchers have created a machine-learning model that enables the sites to "learn" dialect and other medical vernacular, thereby improving their performance for users who use such language themselves.

Called "diaTM" (short for "dialect topic modeling"), the system learns by comparing multiple ...

Researchers discover potential genetic target for heart disease

2010-11-18

CINCINNATI—Researchers at the University of Cincinnati (UC) have found a potential genetic target for heart disease, which could lead to therapies to prevent the development of the nation's No. 1 killer in its initial stages.

These findings will be presented for the first time at the American Heart Association's (AHA) Scientific Sessions in Chicago Nov. 17.

The study, led by WenFeng Cai, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow under the direction of Litsa Kranias, PhD, AHA distinguished scientist and Hanna Chair in Cardiology in the department of pharmacology and cell biophysics, ...

Researchers fight America's 'other drug problem'

2010-11-18

COLUMBIA, Mo. – Medications do not have a chance to fight health problems if they are taken improperly or not taken at all. Non-adherence to medications costs thousands of lives and billions of dollars each year in the United States alone, according to the New England Healthcare Institute. Now, researchers at the University of Missouri have developed an intervention strategy that is three times more effective than previously studied techniques at improving adherence in patients.

Cynthia Russell, associate professor in the MU Sinclair School of Nursing, found that patients ...

Toronto Western Hospital study demonstrates improved wait times for patients suffering back pain

2010-11-18

Results of a Toronto Western Hospital study show that patients suffering back pain get quicker diagnosis and treatment when a Nurse Practitioner conducts the first examination. Traditionally, patients face long and anxiety-ridden wait times - up to 52 weeks – before an initial examination by a spine surgeon. Results from the year long TWH study showed wait times for patients examined by a Nurse Practitioner were significantly shorter, ranging from 10 to 21 weeks.

"Waiting times for specialty consultations in public healthcare systems worldwide are lengthy and impose undue ...

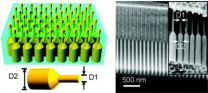

A new twist for nanopillar light collectors

2010-11-18

Sunlight represents the cleanest, greenest and far and away most abundant of all energy sources, and yet its potential remains woefully under-utilized. High costs have been a major deterrant to the large-scale applications of silicon-based solar cells. Nanopillars - densely packed nanoscale arrays of optically active semiconductors - have shown potential for providing a next generation of relatively cheap and scalable solar cells, but have been hampered by efficiency issues. The nanopillar story, however, has taken a new twist and the future for these materials now looks ...

Battling a bat killer

2010-11-18

Scientists are looking for answers — including commercial bathroom disinfectants and over-the-counter fungicides used to fight athlete's foot — to help in the battle against a strange fungus that threatens bat populations in the United States. That's the topic of an article in the current issue of Chemical & Engineering News (C&EN), ACS' weekly newsmagazine.

C&EN Senior Correspondent Stephen K. Ritter notes that despite their poor public image, bats are beneficial. They pollinate plants, spread seeds, and eat vast numbers of insects that otherwise could destroy food ...

Low-allergenic wines could stifle sniffles and sneezes in millions of wine drinkers

2010-11-18

Scientists have identified a mysterious culprit that threatens headaches, stuffy noses, skin rash and other allergy symptoms when more than 500 million people worldwide drink wine. The discovery could help winemakers in developing the first low allergenic vintages — reds and whites with less potential to trigger allergy symptoms, they say. The new study appears in ACS' monthly Journal of Proteome Research.

Giuseppe Palmisano and colleagues note growing concern about the potential of certain ingredients in red and white to cause allergy-like symptoms that range from stuffed ...

Differences in brain development between males and females may hold clues to mental health disorders

2010-11-18

Many mental health disorders, such as autism and schizophrenia, produce changes in social behavior or interactions. The frequency and/or severity of these disorders is substantially greater in boys than girls, but the biological basis for this difference between the two sexes is unknown.

Researchers at the University of Maryland School of Medicine have discovered differences in the development of the amygdala region of the brain – which is critical to the expression of emotional and social behaviors – in animal models that may help to explain why some mental health disorders ...

Advance toward controlling fungus that caused Irish potato famine

2010-11-18

Scientists are reporting a key advance toward development of a way to combat the terrible plant diseases that caused the Irish potato famine and still inflict billions of dollars of damage to crops each year around the world. Their study appears in ACS' bi-weekly journal Organic Letters.

Teck-Peng Loh and colleagues point out that the Phytophthora fungi cause extensive damage to food crops such as potatoes and soybeans as well as to ornamental plants like azaleas and rhododendrons. One species of the fungus caused the Irish potato famine in the mid 1840s. That disaster ...

Study: Employers, workers may benefit from employee reference pool

2010-11-18

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — With employers increasingly reluctant to supply references for former employees in order to avoid legal liability, the creation of a centralized reference pool for workers may make labor markets in the U.S. more efficient, a University of Illinois expert in labor and employment law says.

Law professor Matthew W. Finkin says that not only do employees face challenges when securing references from past employers, but employers also expose themselves to lawsuits when they provide a reference.

"Employees benefit from references, but there's nothing in ...