(Press-News.org) "What a curious feeling," says Alice in Lewis Carroll's tale, as she shrinks to a fraction of her size, and everything around her suddenly looks totally unfamiliar. Scientists too have to get used to these curious feelings when they examine matter on tiny scales and at low temperatures: all the behaviour we are used to seeing around us is turned on its head.

In research published today in the journal Nature Communications, UCL scientists have made a startling discovery about a familiar physical effect in this unfamiliar setting.

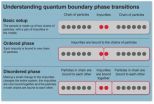

Phase transitions are a category of physical phenomena in which the properties of a sample and the relationships between the particles that make it up suddenly change. Phase transitions include familiar events such as water turning to ice when temperature drops, or a magnet losing its magnetisation when temperature rises.

On human scales, and at ambient temperatures, phase transitions are well understood. They are linked to the temperature (and hence the vibration, orientation and movement of particles) of an object. In quantum physics, however, phase transitions behave slightly differently, and can even occur close to absolute zero, when virtually no heat is present in a sample. These occur when a factor which affects the whole sample, such as a magnetic field, is changed. But in certain cases, quantum phase transitions can also happen when varying a highly localised factor, such as changing the coupling between a single pair of particles on the edge of such a system. These are called boundary phase transitions and would be like melting an entire iceberg by touching a corner of it with a hot poker.

Dr Abolfazl Bayat and Professor Sougato Bose (both UCL Physics & Astronomy), along with colleagues at other institutions, have probed the nature of boundary phase transitions in quantum systems. For the first time they have identified a measurable quantity that can label the distinct phases of such a system.

"When phase transitions happen, scientists often talk of an 'order parameter'," says Bayat. "This is the value which suddenly changes, such as the orientation of magnetisation in a metal, or the spacing of atoms in a sample which determines whether it is liquid or solid. Getting a handle on order parameters in quantum boundary phase transitions is much harder, but we have identified one in this research."

Bayat and Bose studied a system in which a tiny change applied to a single pair of impurities causes a change in the entire system. The two impurities can either be entangled with each other, or can separately be entangled with the left and right hand parts of the system. Changing the pairing of the impurities acts like a switch on the whole system, triggering a phase transition in the form of a sudden change in the entire sample.

"We found that that a quantity called the Schmidt gap has all the features of an order parameter for this phase transition," says Bose. "That means that mathematically it characterizes all the features of the phase transition in an analogous way to how magnetisation does for a magnet".

However, unlike magnetisation, which can be easily measured, the Schmidt gap is a non-localised quantity which requires every particle in a system to be individually measured. Although, this a challenging task, it is becoming viable in recent experiments in ultra-cold atoms.

This research opens up new possibilities for exploring phase transitions in quantum physics. In particular, where conventional methods which use localised order parameters are not applicable, this gives a new means of studying phase transitions. It may help to determine new phases of matter and shed light into the structure of complex systems.

INFORMATION:

Notes to editors

1. For more information or to speak to one of the researchers, please contact Oli Usher in the on tel: +44 (0)20 7679 7964, e-mail: o.usher@ucl.ac.uk

2. An order parameter for impurity systems at quantum criticality is published in Nature Communications on 7 May 2014.

3. Journalists can obtain copies of the paper by contacting the UCL Media Relations Office.

About UCL (University College London)

Founded in 1826, UCL was the first English university established after Oxford and Cambridge, the first to admit students regardless of race, class, religion or gender and the first to provide systematic teaching of law, architecture and medicine.

We are among the world's top universities, as reflected by our performance in a range of international rankings and tables. According to the Thomson Scientific Citation Index, UCL is the second most highly cited European university and the 15th most highly cited in the world.

UCL has nearly 27,000 students from 150 countries and more than 9,000 employees, of whom one third are from outside the UK. The university is based in Bloomsbury in the heart of London, but also has two international campuses – UCL Australia and UCL Qatar. Our annual income is more than £800 million.

http://www.ucl.ac.uk | Follow us on Twitter @uclnews | Watch our YouTube channel YouTube.com/UCLTV

Melting an entire iceberg with a hot poker: Spotting phase changes triggered by impurities

2014-05-07

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Sprites form at plasma irregularities in the lower ionosphere

2014-05-07

Atmospheric sprites have been known for nearly a century, but their origins were a mystery. Now, a team of researchers has evidence that sprites form at plasma irregularities and may be useful in remote sensing of the lower ionosphere.

"We are trying to understand the origins of this phenomenon," said Victor Pasko, professor of electrical engineering, Penn State. "We would like to know how sprites are initiated and how they develop."

Sprites are an optical phenomenon that occur above thunderstorms in the D region of the ionosphere, the area of the atmosphere just above ...

International molecular screening program for metastatic breast cancer AURORA at IMPAKT

2014-05-07

While research has made great strides in recent decades to improve and significantly extend the lives of patients with early breast cancer, the needs of patients with advanced or metastatic disease have largely been ignored. Moreover, despite the fact that the overall breast cancer death rate has dropped steadily over the last decade and significant improvements in survival have been made, metastatic breast cancer represents the leading cause of death among patients with the disease.

In this context the Breast International Group (BIG) recently launched AURORA, which ...

Nearest bright 'hypervelocity star' found

2014-05-07

SALT LAKE CITY, May 7, 2014 – A University of Utah-led team discovered a "hypervelocity star" that is the closest, second-brightest and among the largest of 20 found so far. Speeding at more than 1 million mph, the star may provide clues about the supermassive black hole at the center of our Milky Way and the halo of mysterious "dark matter" surrounding the galaxy, astronomers say.

"The hypervelocity star tells us a lot about our galaxy – especially its center and the dark matter halo," says Zheng Zheng, an assistant professor of physics and astronomy and lead author ...

All teeth and claws? New study sheds light on dinosaur claw function

2014-05-07

Theropod dinosaurs, a group which includes such famous species as Tyrannosaurus rex and Velociraptor, are often regarded as carnivorous and predatory animals, using their sharp teeth and claws to capture and dispatch prey. However, a detailed look at the claws on their forelimbs revealed that the form and shape of theropod claws are highly variable and might also have been used for other tasks.

Inspired by this broad spectrum of claw morphologies, Dr Stephan Lautenschlager from Bristol's School of Earth Sciences studied the differences in claw shape and how these are ...

Revealing the healing of Dino-sores

2014-05-07

Scientists have used state-of-the-art imaging techniques to examine the cracks, fractures and breaks in the bones of a 150 million-year-old predatory dinosaur.

The University of Manchester researchers say their groundbreaking work – using synchrotron-imaging techniques – sheds new light, literally, on the healing process that took place when these magnificent animals were still alive.

The research, published in the Royal Society journal Interface, took advantage of the fact that dinosaur bones occasionally preserve evidence of trauma, sickness and the subsequent signs ...

Study finds pregnant women show increased activity in right side of brain

2014-05-07

Pregnant women show increased activity in the area of the brain related to emotional skills as they prepare to bond with their babies, according to a new study by scientists at Royal Holloway, University of London.

The research, which will be presented at the British Psychological Society's annual conference on Wednesday 7 May, found that pregnant women use the right side of their brain more than new mothers do when they look at faces with emotive expressions.

"Our findings give us a significant insight into the 'baby brain' phenomenon that makes a woman more sensitive ...

Mass vaccination campaigns reduce the substantial burden of yellow fever in Africa

2014-05-07

Yellow fever, an acute viral disease, is estimated to have been responsible for 78,000 deaths in Africa in 2013 according to new research published in PLOS Medicine this week. The research by Neil Ferguson from Imperial College London, UK and colleagues from Imperial College, WHO and other institutions also estimates that recent mass vaccination campaigns against yellow fever have led to a 27% decrease in the burden of yellow fever across Africa in 2013.

Yellow fever is a serious viral disease that affects people living in and visiting tropical regions of Africa and ...

Water from improved sources is not consistently safe

2014-05-07

Although water from improved sources (such as piped water and bore holes) is less likely to contain fecal contamination than water from unimproved sources, improved sources in low- and middle-income countries are not consistently safe, according to a study by US and UK researchers, published in this week's PLOS Medicine.

These findings are important as WHO and UNICEF track progress towards the Millennium Development Goals water target using the indicator "use of an improved source": this study shows that assuming that "improved" water sources are safe greatly overestimates ...

Dinosaurs and birds kept evolving by shrinking

2014-05-07

Although most dinosaurs went extinct 65 million years ago, one dinosaur lineage survived and lives on today as a major evolutionary success story – the birds. But to what does this lineage owe its success? A study that has 'weighed' hundreds of dinosaurs now suggests that shrinking their bodies may have helped this group to continue exploiting new ecological niches throughout their evolution, and to become such a diverse and widespread group of animals today.

An international team, led by scientists from Oxford University and the Royal Ontario Museum, estimated the body ...

Shrinking helped dinosaurs and birds to keep evolving

2014-05-07

A study that has 'weighed' hundreds of dinosaurs suggests that shrinking their bodies may have helped the group that became birds to continue exploiting new ecological niches throughout their evolution, and become hugely successful today.

An international team, led by scientists at Oxford University and the Royal Ontario Museum, estimated the body mass of 426 dinosaur species based on the thickness of their leg bones. The team found that dinosaurs showed rapid rates of body size evolution shortly after their origins, around 220 million years ago. However, these soon slowed: ...