(Press-News.org) Vast amounts of excess heat are generated by industrial processes and by electric power plants. Researchers around the world have spent decades seeking ways to harness some of this wasted energy. Most such efforts have focused on thermoelectric devices – solid-state materials that can produce electricity from a temperature gradient – but the efficiency of such devices is limited by the availability of materials.

Now researchers at Stanford University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology have found a new alternative for low-temperature waste-heat conversion into electricity – that is, in cases where temperature differences are less than 100 degrees Celsius.

The new approach is described in a study, published in the May 21 issue of the journal Nature Communications, by Seok Woo Lee and Yi Cui at Stanford and Yuan Yang and Gang Chen at MIT.

"Virtually all power plants and manufacturing processes, like steelmaking and refining, release tremendous amounts of low-grade heat to ambient temperatures," said Cui, an associate professor of materials science and engineering. "Our new battery technology is designed to take advantage of this temperature gradient at the industrial scale."

Voltage and temperature

The new Stanford-MIT system is based on the principle known as the thermogalvanic effect, which states that the voltage of a rechargeable battery is dependent on temperature. "To harvest thermal energy, we subject a battery to a four-step process: heating up, charging, cooling down and discharging," said Lee, a postdoctoral scholar at Stanford and co-lead author of the study.

First, an uncharged battery is heated by waste heat. Then, while the battery is still warm, a voltage is applied. Once fully charged, the battery is allowed to cool. Because of the thermogalvanic effect, the voltage increases as the temperature decreases. When the battery has cooled, it actually delivers more electricity than was used to charge it. That extra energy doesn't appear from nowhere, explained Cui. It comes from the heat that was added to the system.

The Stanford-MIT system aims at harvesting heat at temperatures below 100 C, which accounts for a major part of potentially harvestable waste heat. "One-third of all energy consumption in the United States ends up as low-grade heat," said co-lead author Yang, a postdoc at MIT.

In the experiment, a battery was heated to 60 C, charged and cooled. The process resulted in an electricity-conversion efficiency of 5.7 percent, almost double the efficiency of conventional thermoelectric devices.

This heating-charging-cooling approach was first proposed in the 1950s at temperatures of 500 C or more, said Yang, noting that most heat recovery systems work best with higher temperature differences.

"A key advance is using material that was not around at that time" for the battery electrodes, as well as advances in engineering the system, said co-author Chen, a professor of mechanical engineering at MIT.

"This technology has the additional advantage of using low-cost, abundant materials and manufacturing processes that are already widely used in the battery industry," added Lee.

'Clever idea'

While the new system has a significant advantage in energy-conversion efficiency over conventional thermoelectric devices, it has a much lower power density – that is, the amount of power that can be delivered for a given weight. The new technology also will require further research to assure long-term reliability and improve the speed of battery charging and discharging, Chen added. "It will require a lot of work to take the next step."

There is currently no good technology that can make effective use of the relatively low-temperature differences this system can harness, Chen said. "This has an efficiency we think is quite attractive. There is so much of this low-temperature waste heat, if a technology can be created and deployed to use it."

The results are very promising, said Peidong Yang, a professor of chemistry at the University of California, Berkeley, who was not involved in the study. "By exploring the thermogalvanic effect, [the MIT and Stanford researchers] were able to convert low-grade heat to electricity with decent efficiency," he said. "This is a clever idea, and low-grade waste heat is everywhere."

INFORMATION:

Other authors of the study are Hyun-Wook Lee of Stanford and Hadi Ghasemi and Daniel Kraemer of MIT.

The Stanford work was partially funded by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and the National Research Foundation of Korea. The MIT work was partially funded by the DOE, in part through the Solid-State Solar-Thermal Energy Conversion Center.

This article is based on a report from the MIT News Office.

Stanford, MIT scientists find new way to harness waste heat

2014-05-22

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

A new target for alcoholism treatment: Kappa opioid receptors

2014-05-22

Philadelphia, PA, May 22, 2014 – The list of brain receptor targets for opiates reads like a fraternity: Mu Delta Kappa. The mu opioid receptor is the primary target for morphine and endogenous opioids like endorphin, whereas the delta opioid receptor shows the highest affinity for endogenous enkephalins. The kappa opioid receptor (KOR) is very interesting, but the least understood of the opiate receptor family.

Until now, the mu opioid receptor received the most attention in alcoholism research. Naltrexone, a drug approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for ...

Higher discharge rate for BPD in children and adolescents in the US compared to UK

2014-05-22

Washington D.C., May 22, 2014 – A study published in the June 2014 issue of the Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry found a very much higher discharge rate for pediatric bipolar (PBD) in children and adolescents aged 1-19 years in the US compared to England between the years 2000-2010.

Using the English NHS Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) dataset and the US National Hospital Discharge Survey (NHDS) to compare US and English discharge rates for PBD over the period 2000-2010, the authors found a 72.1-fold higher discharge rate for pediatric ...

Liquid crystal as lubricant

2014-05-22

Lubricants are used in motors, axels, ventilators and manufacturing machines. Although lubricants are widely used, there have been almost no fundamental innovations for this product in the last twenty years. Together with a consortium, the Fraunhofer Institute for Mechanics of Materials IWM in Freiburg has developed an entirely new class of substance that could change everything: liquid crystalline lubricant. Its chemical makeup sets it apart; although it is a liquid, the molecules display directional properties like crystals do. When two surfaces move in opposite directions, ...

Fossil avatars are transforming palaeontology

2014-05-22

Palaeontology has traditionally proceeded slowly, with individual scientists labouring for years or even decades over the interpretation of single fossils which they have gradually recovered from entombing rock, sand grain by sand grain, using all manner of dental drills and needles.

The introduction of X-ray tomography has revolutionized the way that fossils are studied, allowing them to be virtually extracted from the rock in a fraction of the time necessary to prepare specimens by hand and without the risk of damaging the fossil.

The resulting fossil avatars not ...

Drug-target database lets researchers match old drugs to new uses

2014-05-22

There are thousands of drugs that silence many thousands of cancer-causing genetic abnormalities. Some of these drugs are in use now, but many of these drugs are sitting on shelves or could be used beyond the disease for which they were originally approved. Repurposing these drugs depends on matching drugs to targets. A study recently published in the journal Bioinformatics describes a new database and pattern-matching algorithm that allows researchers to evaluate rational drugs and drug combinations, and also recommends a new drug combination to treat drug-resistant non-small ...

TSRI scientists catch misguided DNA-repair proteins in the act

2014-05-22

LA JOLLA, CA – May 22, 2014 – Accumulation of DNA damage can cause aggressive forms of cancer and accelerated aging, so the body's DNA repair mechanisms are normally key to good health. However, in some diseases the DNA repair machinery can become harmful. Scientists led by a group of researchers at The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) in La Jolla, CA, have discovered some of the key proteins involved in one type of DNA repair gone awry.

The focus of the new study, published in the May 22, 2014 edition of the journal Cell Reports, is a protein called Ring1b. The TSRI ...

Univ. of MD researchers identify fat-storage gene mutation that may increase diabetes risk

2014-05-22

BALTIMORE – May 21, 2014. Researchers at the University of Maryland School of Medicine have identified a mutation in a fat-storage gene that appears to increase the risk for type 2 diabetes and other metabolic disorders, according to a study published online today in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The researchers discovered the mutation in the hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL) gene by studying the DNA of more than 2,700 people in the Old Order Amish community in Lancaster County, Pa. HSL is a key enzyme involved in breaking down stored fat (triglycerides) into fatty ...

Ka'ena Volcano: First building block for O'ahu discovered

2014-05-22

Boulder, Colo., USA – Researcher John Sinton of the University of Hawai'i along with colleagues from the Monterrey Bay Aquarium and the French National Center for Scientific Research have announced the discovery of an ancient Hawaiian volcano. Now located in a region of shallow bathymetry extending about 100 km WNW from Ka'ena Point at the western tip of O'ahu, this volcano, which they have named Ka'ena, would have risen about 1,000 meters above sea level 3.5 million years ago.

Sinton and colleagues have found compelling evidence beneath the sea that this long-lived ...

Intuitions about the causes of rising obesity are often wrong, researchers report

2014-05-22

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — Everything you think you know about the causes of rising obesity in the U.S. might be wrong, researchers say in a new report.

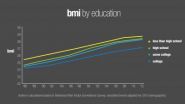

Contrary to popular belief, people are exercising more today, have more leisure time and better access to fresh, affordable food – including fruits and vegetables – than they did in past decades. And while troubling disparities exist among various groups, most economic, educational, and racial or ethnic groups have seen their obesity levels rise at similar rates since the mid-1980s, the researchers report.

The new analysis appears ...

Review says inexpensive food a key factor in rising obesity

2014-05-22

ATLANTA May 22, 2014—A new review summarizes what is known about economic factors tied to the obesity epidemic in the United States and concludes many common beliefs are wrong. The review, authored by Roland Sturm, PhD of RAND Corporation and Ruopeng An, PhD, of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, notes that paradoxically, rising obesity rates coincided with increases in leisure time, increased fruit and vegetable availability, and increased exercise uptake. The review appears early online in CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians and finds at least one factor ...