(Press-News.org) VIDEO:

This video shows how the constant addition of tubulin bound to GTP provides a cap that prevents the microtubule from falling apart. UC Berkeley scientists found that the hydrolyzation of...

Click here for more information.

University of California, Berkeley, scientists have discovered the extremely subtle effect that the prescription drug Taxol has inside cells that makes it one of the most widely used anticancer agents in the world.

The details, involving the drug's interference with the normal function of microtubules, part of the cell's skeleton, could help in designing better anticancer drugs, or in improving Taxol and other drugs already known to disrupt the workings of microtubules.

The findings are being reported in the May 22 issue of the journal Cell.

"Efforts towards understanding these chemotherapeutics better are very important, because there are some microtubule differences in cancer cells versus normal cells that maybe we can exploit," said principle author Eva Nogales, a biophysicist, UC Berkeley professor of molecular and cell biology and senior faculty scientist at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL). "We are not there yet, but this is the kind of analysis we need to get there."

Taxol, originally extracted from the bark of the Pacific yew tree, is one of the mostly commonly used drugs against solid tumors, and is a front-line drug for treating ovarian and advanced breast cancer. The drug is known to bind to microtubules and essentially freeze them in place, which prevents them from separating the chromosomes when a cell divides. This kills dividing cells, in particular cancer cells, which are known for rapid proliferation.

Nogales, a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator, has worked on microtubules since she was a doctoral student in England in the early '90s, using techniques such as X-ray scattering and cryoelectron microscopy to study how Taxol and other anticancer agents affect microtubules. Later, during her postdoctoral work at LBNL with Ken Downing, she was the first to discover exactly where Taxol binds the basic building block, called tubulin, of the microtubule polymer.

Microtubules are the cell's skeleton

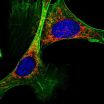

Work by many scientists around the world has shown the microtubule network inside cells, called the cytoskeleton, to be very different from rigid animal skeletons. Microtubules are polymer filaments that constantly grow and shrink, and in doing so push and pull things around the cell, including the chromosomes. Scientists call this dynamic instability. The microtubules also provide a highway for transporting the cell's organelles and other packages around the cell.

Tubulin, the basic structural unit of the microtubule, is a complex of two proteins – alpha and beta tubulin. Tubulin units stack one atop another to form strips that align with other strips and then zip up to form a hollow tube, the microtubule.

"Tubulin, the cytoskeletal protein that self-assembles into microtubules, is absolutely essential for the life of every eukaryotic cell, which is why it has become a major target of anticancer agents," Nogales said. "It's amazing how microtubules probe and try new things almost at random, but there is a level of control built into the cell that ultimately makes sense of this chaos, and the cell survives and prospers."

VIDEO:

This video shows how the microtubule rapidly peels apart once the growing tubulin cap disappears. This peeling or depolymerization does work inside the cell. A chromosome attached by its kinetochore...

Click here for more information.

Microtubules grow from their free end at about 1 micron per minute by continually adding more tubulin (around 20 tubulin molecules per second). But if they stop growing, they rapidly peel apart like the skin of a banana, releasing tubulin for recycling into other microtubules. This peeling, or depolymerization, takes place at up to 15 microns per minute, or about 300 tubulin molecules falling off per second, Nogales said.

Microtubules are like compressed springs

Nogales has now discovered why microtubules peel apart so rapidly. When they assemble, the strips of tubulin are put under intense strain, but prevented from bending and pulling apart by the growing cap of tubulin on the end. Once growing stops and that cap disappears, the restrained tension rips the microtubule apart.

The tension is created when the tubulin complex, which has a small energy molecule called GTP (guanosine triphosphate) attached, becomes hydrolyzed and the GTP turns into GDP (guanosine diphosphate). This chemical reaction compacts the alpha and beta subunits, much like compacted vertebrae, keeping the tubulin stack under tension as long as the microtubule is growing at its end.

"It had been proposed that tubulin had to be constrained, but no one had proved it," Nogales said. "What we have seen is that as GTP hydrolysis happens, the tubulin structure gets stuck in a strained state, like a compressed spring. The end subunits are holding the whole thing together."

When growth stops, the tension is unleashed, and the strips peel apart rapidly.

"This work represents a major step forward on a problem with a long history," wrote Tim Mitchison in a commentary in the same issue of Cell. Mitchison, a Harvard University professor of systems biology, was the first to show the importance of GTP hydrolysis in destabilizing microtubules. The model proposed by Nogales and her team, he added, "provides our first glimpse into (the) destabilization mechanism."

Nogales also found that Taxol inserts itself into the tubulin protein and prevents compaction of the alpha and beta subunits, so that no tension builds up. As a result, even if the microtubule stops growing, it remains intact, basically frozen in place, unable to peel apart, or depolymerize, and carry out its normal function.

"Taxol reverses the effects of GTP hydrolysis," she said.

Nogales and her team discovered these structural changes by pushing the limits of cryoelectron microscopy, a technique in which samples are frozen and probed with a high-powered electron beam. They have now achieved a resolution sufficient to see details smaller than 5 angstroms (one-tenth of a nanometer) across, which is about the size of five hydrogen atoms. While most information to date about the structure of tubulin inside the microtubule has come from the study of artificial, flat sheets of aligned strips of tubulin, Nogales was able to probe three-dimensional microtubules frozen into their natural state, with and without Taxol bound to tubulin. This comparison clearly showed the effect Taxol has on microtubule structure.

INFORMATION:

Other coauthors of the paper are former UC Berkeley biophysics graduate student Gregory M. Alushin, now of the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute in Bethesda, Md.; former LBNL postdoc Gabriel C. Lander, now of The Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, Calif.; Elizabeth H. Kellogg of UC Berkeley; Rui Zhang of LBNL and David Baker of the University of Washington, Seattle.

The research is funded by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (GM051487), the Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Discovery of how Taxol works could lead to better anticancer drugs

Drug interferes with compaction of microtubule polymer, preventing it from springing apart

2014-05-22

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Gene behind unhealthy adipose tissue identified

2014-05-22

Researchers at Karolinska Institutet in Sweden have for the first time identified a gene driving the development of pernicious adipose tissue in humans. The findings imply, which are published in the scientific journal Cell Metabolism, that the gene may constitute a risk factor promoting the development of insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes.

Adipose tissue can expand in two ways: by increasing the size and/or the number of the fat cells. It is well established that subjects with few but large fat cells, so-called hypertrophy, display an increased risk of developing ...

Computer models helping unravel the science of life?

2014-05-22

Scientists have developed a sophisticated computer modelling simulation to explore how cells of the fruit fly react to changes in the environment.

The research, published today in the science journal Cell, is part of an on-going study at The Universities of Manchester and Sheffield that is investigating how external environmental factors impact on health and disease.

The model shows how cells of the fruit fly communicate with each other during its development. Dr Martin Baron, who led the research, said: "The work is a really nice example of researchers from different ...

Supportive tissue in tumors hinders, rather than helps, pancreatic cancer

2014-05-22

HOUSTON – Fibrous tissue long suspected of making pancreatic cancer worse actually supports an immune attack that slows tumor progression but cannot overcome it, scientists at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center report in the journal Cancer Cell.

"This supportive tissue that's abundant in pancreatic cancer tumors is not a traitor as we thought but rather an ally that is fighting to the end. It's a losing battle with cancer cells, but progression is much faster without their constant resistance," said study senior author Raghu Kalluri, Ph.D., M.D., chair ...

Blocking pain receptors extends lifespan, boosts metabolism in mice

2014-05-22

Blocking a pain receptor in mice not only extends their lifespan, it also gives them a more youthful metabolism, including an improved insulin response that allows them to deal better with high blood sugar.

"We think that blocking this pain receptor and pathway could be very, very useful not only for relieving pain, but for improving lifespan and metabolic health, and in particular for treating diabetes and obesity in humans," said Andrew Dillin, a professor of molecular and cell biology at the University of California, Berkeley, and senior author of a new paper describing ...

One molecule to block both pain and itch

2014-05-22

Duke University researchers have found an antibody that simultaneously blocks the sensations of pain and itching in studies with mice.

The new antibody works by targeting the voltage-sensitive sodium channels in the cell membrane of neurons. The results appear online on May 22 in Cell.

Voltage-sensitive sodium channels control the flow of sodium ions through the neuron's membrane. These channels open and close by responding to the electric current or action potential of the cells. One particular type of sodium channel, called the Nav1.7 subtype, is responsible for ...

Deciphered the process through which cells optimize metabolism to burn sugars or fats

2014-05-22

To guarantee efficient use of nutrients, cells have systems that permit them to capture and transport the available nutrient molecules to their interior. But if several nutrients are available, cells can select those that are of most interest and discard undesired molecules.

Inside cells, nutrients are conducted to the mitochondria, the specialized cell organelles in which nutrients are combusted to release the energy held in their chemical bonds. Both sugars (glucose) and fats (fatty acids) are 'burned' in mitochondria, but these organelles need to adjust their molecular ...

New insight into stem cell development

2014-05-22

The world has great expectations that stem cell research one day will revolutionize medicine. But in order to exploit the potential of stem cells, we need to understand how their development is regulated. Now researchers from University of Southern Denmark offer new insight.

Stem cells are cells that are able to develop into different specialized cell types with specific functions in the body. In adult humans these cells play an important role in tissue regeneration. The potential to act as repair cells can be exploited for disease control of e.g. Parkinson's or diabetes, ...

Study: Some pancreatic cancer treatments may be going after the wrong targets

2014-05-22

ANN ARBOR, Mich. — New research represents a significant change in the understanding of how pancreatic cancer grows – and how it might be defeated.

Unlike other types of cancer, pancreatic cancer produces a lot of scar tissue and inflammation. For years, researchers believed that this scar tissue, called desmoplasia, helped the tumor grow, and they've designed treatments to attack this.

But new research led by Andrew D. Rhim, M.D., from the University of Michigan Comprehensive Cancer Center, finds that when you eliminate desmoplasia, tumors grow even more quickly and ...

'I can' mentality goes long way after childbirth

2014-05-22

The way a woman feels about tackling everyday physical activities, including exercise, may be a predictor of how much weight she'll retain years after childbirth says a Michigan State University professor.

James Pivarnik, a professor of kinesiology and epidemiology at MSU, co-led a study that followed 56 women during pregnancy and measured their physical activity levels, along with barriers to exercise and the ability to overcome them.

Six years later, the research team followed up with more than half of the participants and found that the women who considered themselves ...

What is being said in the media and academic literature about neurostimulation?

2014-05-22

Over the past several decades, neurostimulation techniques such as transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) have gradually gained favour in the public eye. In a new report, published yesterday in the prestigious scientific journal Neuron, IRCM ethics experts raise important questions about the rising tide of tDCS coverage in the media, while regulatory action is lacking and ethical issues need to be addressed.

TDCS is a non-invasive form of neurostimulation, in which constant, low current is delivered directly to areas of the brain using small electrodes. Originally ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Roadmap for Europe’s biodiversity monitoring system

Novel camel antimicrobial peptides show promise against drug-resistant bacteria

Scientists discover why we know when to stop scratching an itch

A hidden reason inner ear cells die – and what it means for preventing hearing loss

Researchers discover how tuberculosis bacteria use a “stealth” mechanism to evade the immune system

New microscopy technique lets scientists see cells in unprecedented detail and color

Sometimes less is more: Scientists rethink how to pack medicine into tiny delivery capsules

Scientists build low-cost microscope to study living cells in zero gravity

The Biophysical Journal names Denis V. Titov the 2025 Paper of the Year-Early Career Investigator awardee

Scientists show how your body senses cold—and why menthol feels cool

Scientists deliver new molecule for getting DNA into cells

Study reveals insights about brain regions linked to OCD, informing potential treatments

Does ocean saltiness influence El Niño?

2026 Young Investigators: ONR celebrates new talent tackling warfighter challenges

Genetics help explain who gets the ‘telltale tingle’ from music, art and literature

Many Americans misunderstand medical aid in dying laws

Researchers publish landmark infectious disease study in ‘Science’

New NSF award supports innovative role-playing game approach to strengthening research security in academia

Kumar named to ACMA Emerging Leaders Program for 2026

AI language models could transform aquatic environmental risk assessment

New isotope tools reveal hidden pathways reshaping the global nitrogen cycle

Study reveals how antibiotic structure controls removal from water using biochar

Why chronic pain lasts longer in women: Immune cells offer clues

Toxic exposure creates epigenetic disease risk over 20 generations

More time spent on social media linked to steroid use intentions among boys and men

New study suggests a “kick it while it’s down” approach to cancer treatment could improve cure rates

Milken Institute, Ann Theodore Foundation launch new grant to support clinical trial for potential sarcoidosis treatment

New strategies boost effectiveness of CAR-NK therapy against cancer

Study: Adolescent cannabis use linked to doubling risk of psychotic and bipolar disorders

Invisible harms: drug-related deaths spike after hurricanes and tropical storms

[Press-News.org] Discovery of how Taxol works could lead to better anticancer drugsDrug interferes with compaction of microtubule polymer, preventing it from springing apart