(Press-News.org) LA JOLLA—For most people, the urge to eat a meal or snack comes at a few, predictable times during the waking part of the day. But for those with a rare syndrome, hunger comes at unwanted hours, interrupts sleep and causes overeating.

Now, Salk scientists have discovered a pair of genes that normally keeps eating schedules in sync with daily sleep rhythms, and, when mutated, may play a role in so-called night eating syndrome. In mice with mutations in one of the genes, eating patterns are shifted, leading to unusual mealtimes and weight gain. The results were published in this month's Cell Reports.

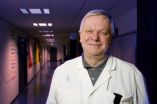

"We really never expected that we would be able to decouple the sleep-wake cycle and the eating cycle, especially with a simple mutation," says senior study author Satchidananda Panda, an associate professor in Salk's Regulatory Biology Laboratory. "It opens up a whole lot of future questions about how these cycles are regulated."

More than a decade ago, researchers discovered that individuals with an inherited sleep disorder often carry a particular mutation in a protein called PER2. The mutation is in an area of the protein that can be phosphorylated—the ability to bond with a phosphate chemical that changes the protein's function. Humans have three PER, or period, genes, all thought to play a role in the daily circadian clock and all containing the same phosphorylation spot.

The Salk scientists joined forces with a Chinese team led by Ying Xu of Nanjing University to test whether mutations in the equivalent area of PER1 would have the same effect as those in PER2 that caused the sleep disorder. So they bred mice to lack the mouse period genes, and added in a human PER1 or PER2 with a mutation in the phosphorylation site. As expected, mice with a mutated PER2 had sleep defects, dozing off earlier than usual. The same wasn't true for PER1 mutations though.

"In the mice without PER1, there was no obvious defect in their sleep-wake cycles," says Panda. "Instead, when we looked at their metabolism, we suddenly saw drastic changes."

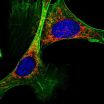

Mice with the PER1 phosphorylation defects ate earlier than other mice—overlapping with their sleep hours—and ate more food throughout the day. When the researchers looked at the molecular details of the PER1 protein, they found that the mutated PER1 led to lower protein levels during the night, higher levels during the day, and a faster degradation of protein whenever it was produced by cells.

Panda and his colleagues hypothesize that normally, PER1 and PER2 are kept synchronized since they have identical phosphorylation sites—they are turned on and off at the same times, keeping sleep and eating cycles aligned. But a mutation in one of the genes could break this link, and cause off-cycle eating or sleeping.

"For a long time, people discounted night eating syndrome as not real," says Panda. "These results in mice suggest that it could actually be a genetic basis for the syndrome." The researchers haven't yet tested, however, whether any humans with night eating syndrome have mutations in PER1.

When Panda and Xu's team restricted access to food, providing it only at the mice's normal meal times, they found that even with a genetic mutation in PER1, mice could maintain a normal weight. Over a 10-week follow-up, these mice—with a PER1 mutation but timed access to food—showed no differences to control animals. This tells the researchers that the weight gain caused by PER1 is entirely caused by meal mistiming, not other metabolic defects.

Next, they hope to study exactly how PER1 controls appetite and eating behavior—whether its molecular actions work through the liver, fat cells, brain or other organs.

INFORMATION:

Other researchers on the study were Zhiwei Liu, Xi Wu, Guangsen Shi, Lijuan Xing, Zhen Dong, Zhipeng Qu, Jie Yan, and Ying Xu of Nanjing University, and Ling Yang of Soochow University.

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute of Health, USA, the Ministry of Science and Technology of China, the National Science Foundation of China.

About the Salk Institute for Biological Studies:

The Salk Institute for Biological Studies is one of the world's preeminent basic research institutions, where internationally renowned faculty probes fundamental life science questions in a unique, collaborative and creative environment. Focused both on discovery and on mentoring future generations of researchers, Salk scientists make groundbreaking contributions to our understanding of cancer, aging, Alzheimer's, diabetes and infectious diseases by studying neuroscience, genetics, cell and plant biology, and related disciplines. Faculty achievements have been recognized with numerous honors, including Nobel Prizes and memberships in the National Academy of Sciences. Founded in 1960 by polio vaccine pioneer Jonas Salk, M.D., the Institute is an independent nonprofit organization and architectural landmark.

Genes discovered linking circadian clock with eating schedule

Mutations in the circadian genes could drive night eating syndrome

2014-05-22

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

New technology may help identify safe alternatives to BPA

2014-05-22

Numerous studies have linked exposure to bisphenol A (BPA) in plastic, receipt paper, toys, and other products with various health problems from poor growth to cancer, and the FDA has been supporting efforts to find and use alternatives. But are these alternatives safer? Researchers reporting in the Cell Press journal Chemistry & Biology have developed new tests that can classify such compounds' activity with great detail and speed. The advance could offer a fast and cost-effective way to identify safe replacements for BPA.

Millions of tons of BPA and related compounds ...

Discovery of how Taxol works could lead to better anticancer drugs

2014-05-22

VIDEO:

This video shows how the constant addition of tubulin bound to GTP provides a cap that prevents the microtubule from falling apart. UC Berkeley scientists found that the hydrolyzation of...

Click here for more information.

University of California, Berkeley, scientists have discovered the extremely subtle effect that the prescription drug Taxol has inside cells that makes it one of the most widely used anticancer agents in the world.

The details, involving the drug's ...

Gene behind unhealthy adipose tissue identified

2014-05-22

Researchers at Karolinska Institutet in Sweden have for the first time identified a gene driving the development of pernicious adipose tissue in humans. The findings imply, which are published in the scientific journal Cell Metabolism, that the gene may constitute a risk factor promoting the development of insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes.

Adipose tissue can expand in two ways: by increasing the size and/or the number of the fat cells. It is well established that subjects with few but large fat cells, so-called hypertrophy, display an increased risk of developing ...

Computer models helping unravel the science of life?

2014-05-22

Scientists have developed a sophisticated computer modelling simulation to explore how cells of the fruit fly react to changes in the environment.

The research, published today in the science journal Cell, is part of an on-going study at The Universities of Manchester and Sheffield that is investigating how external environmental factors impact on health and disease.

The model shows how cells of the fruit fly communicate with each other during its development. Dr Martin Baron, who led the research, said: "The work is a really nice example of researchers from different ...

Supportive tissue in tumors hinders, rather than helps, pancreatic cancer

2014-05-22

HOUSTON – Fibrous tissue long suspected of making pancreatic cancer worse actually supports an immune attack that slows tumor progression but cannot overcome it, scientists at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center report in the journal Cancer Cell.

"This supportive tissue that's abundant in pancreatic cancer tumors is not a traitor as we thought but rather an ally that is fighting to the end. It's a losing battle with cancer cells, but progression is much faster without their constant resistance," said study senior author Raghu Kalluri, Ph.D., M.D., chair ...

Blocking pain receptors extends lifespan, boosts metabolism in mice

2014-05-22

Blocking a pain receptor in mice not only extends their lifespan, it also gives them a more youthful metabolism, including an improved insulin response that allows them to deal better with high blood sugar.

"We think that blocking this pain receptor and pathway could be very, very useful not only for relieving pain, but for improving lifespan and metabolic health, and in particular for treating diabetes and obesity in humans," said Andrew Dillin, a professor of molecular and cell biology at the University of California, Berkeley, and senior author of a new paper describing ...

One molecule to block both pain and itch

2014-05-22

Duke University researchers have found an antibody that simultaneously blocks the sensations of pain and itching in studies with mice.

The new antibody works by targeting the voltage-sensitive sodium channels in the cell membrane of neurons. The results appear online on May 22 in Cell.

Voltage-sensitive sodium channels control the flow of sodium ions through the neuron's membrane. These channels open and close by responding to the electric current or action potential of the cells. One particular type of sodium channel, called the Nav1.7 subtype, is responsible for ...

Deciphered the process through which cells optimize metabolism to burn sugars or fats

2014-05-22

To guarantee efficient use of nutrients, cells have systems that permit them to capture and transport the available nutrient molecules to their interior. But if several nutrients are available, cells can select those that are of most interest and discard undesired molecules.

Inside cells, nutrients are conducted to the mitochondria, the specialized cell organelles in which nutrients are combusted to release the energy held in their chemical bonds. Both sugars (glucose) and fats (fatty acids) are 'burned' in mitochondria, but these organelles need to adjust their molecular ...

New insight into stem cell development

2014-05-22

The world has great expectations that stem cell research one day will revolutionize medicine. But in order to exploit the potential of stem cells, we need to understand how their development is regulated. Now researchers from University of Southern Denmark offer new insight.

Stem cells are cells that are able to develop into different specialized cell types with specific functions in the body. In adult humans these cells play an important role in tissue regeneration. The potential to act as repair cells can be exploited for disease control of e.g. Parkinson's or diabetes, ...

Study: Some pancreatic cancer treatments may be going after the wrong targets

2014-05-22

ANN ARBOR, Mich. — New research represents a significant change in the understanding of how pancreatic cancer grows – and how it might be defeated.

Unlike other types of cancer, pancreatic cancer produces a lot of scar tissue and inflammation. For years, researchers believed that this scar tissue, called desmoplasia, helped the tumor grow, and they've designed treatments to attack this.

But new research led by Andrew D. Rhim, M.D., from the University of Michigan Comprehensive Cancer Center, finds that when you eliminate desmoplasia, tumors grow even more quickly and ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Roadmap for Europe’s biodiversity monitoring system

Novel camel antimicrobial peptides show promise against drug-resistant bacteria

Scientists discover why we know when to stop scratching an itch

A hidden reason inner ear cells die – and what it means for preventing hearing loss

Researchers discover how tuberculosis bacteria use a “stealth” mechanism to evade the immune system

New microscopy technique lets scientists see cells in unprecedented detail and color

Sometimes less is more: Scientists rethink how to pack medicine into tiny delivery capsules

Scientists build low-cost microscope to study living cells in zero gravity

The Biophysical Journal names Denis V. Titov the 2025 Paper of the Year-Early Career Investigator awardee

Scientists show how your body senses cold—and why menthol feels cool

Scientists deliver new molecule for getting DNA into cells

Study reveals insights about brain regions linked to OCD, informing potential treatments

Does ocean saltiness influence El Niño?

2026 Young Investigators: ONR celebrates new talent tackling warfighter challenges

Genetics help explain who gets the ‘telltale tingle’ from music, art and literature

Many Americans misunderstand medical aid in dying laws

Researchers publish landmark infectious disease study in ‘Science’

New NSF award supports innovative role-playing game approach to strengthening research security in academia

Kumar named to ACMA Emerging Leaders Program for 2026

AI language models could transform aquatic environmental risk assessment

New isotope tools reveal hidden pathways reshaping the global nitrogen cycle

Study reveals how antibiotic structure controls removal from water using biochar

Why chronic pain lasts longer in women: Immune cells offer clues

Toxic exposure creates epigenetic disease risk over 20 generations

More time spent on social media linked to steroid use intentions among boys and men

New study suggests a “kick it while it’s down” approach to cancer treatment could improve cure rates

Milken Institute, Ann Theodore Foundation launch new grant to support clinical trial for potential sarcoidosis treatment

New strategies boost effectiveness of CAR-NK therapy against cancer

Study: Adolescent cannabis use linked to doubling risk of psychotic and bipolar disorders

Invisible harms: drug-related deaths spike after hurricanes and tropical storms

[Press-News.org] Genes discovered linking circadian clock with eating scheduleMutations in the circadian genes could drive night eating syndrome