(Press-News.org) Scientists at the U.S. Department of Energy's Argonne National Laboratory have discovered a previously unknown phase in a class of superconductors called iron arsenides. This sheds light on a debate over the interactions between atoms and electrons that are responsible for their unusual superconductivity.

"This new magnetic phase, which has never been observed before, could have significant implications for our understanding of unconventional superconductivity," said Ray Osborn, an Argonne physicist and coauthor on the paper.

Scientists and engineers are fascinated with superconductors because they are capable of carrying electric current without any resistance. This is unique among all conductors: even good ones, like the copper wires used in most power cords, lose energy along the way.

Why don't we use superconductors for every power line in the country, then? Their biggest drawback is that they must be cooled to very, very cold temperatures to work. Also, we do not fully understand how the newest types, called unconventional superconductors, work. Researchers hope that by figuring out the theory behind these superconductors, we could raise the temperature at which they work and harness their power for a wide range of new technologies.

The theory behind older, "conventional" superconductors is fairly well understood. Pairs of electrons, which normally repel each other, instead bind together by distorting the atoms around them and help each other travel through the metal. (In a plain old conductor, these electrons bounce off the atoms, producing heat). In "unconventional" superconductors, the electrons still form pairs, but we don't know what binds them together.

Superconductors are notably finicky; in order to get to the superconducting phase—where electricity flows freely—they need a lot of coddling. The iron arsenides the researchers studied are normally magnetic, but as you add sodium to the mix, the magnetism is suppressed and the materials eventually become superconducting below roughly -400 degrees Fahrenheit.

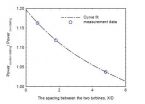

Magnetic order also affects the atomic structure. At room temperature, the iron atoms sit on a square lattice, which has four-fold symmetry, but when cooled below the magnetic transition temperature, they distort to form a rectangular lattice, with only two-fold symmetry. This is sometimes called "nematic order." It was thought that this nematic order persists until the material becomes superconducting—until this result.

The Argonne team discovered a phase where the material returns to four-fold symmetry, rather than two-fold, close to the onset of superconductivity. (See diagram).

"It is visible using neutron powder diffraction, which is exquisitely sensitive, but which you can only perform at this resolution in a very few places in the world," Osborn said.

Neutron powder diffraction reveals both the locations of the atoms and the directions of their microscopic magnetic moments.

The reason why the discovery of the new phase is interesting is that it may help to resolve a long-standing debate about the origin of nematic order. Theorists have been arguing whether it is caused by magnetism or by orbital ordering.

The orbital explanation posits that electrons like to sit in particular d orbitals, driving the lattice into the nematic phase. Magnetic models, on the other hand (developed by study co-authors Ilya Eremin and Andrey Chubukov at the Institut für Theoretische Physik in Germany and the University of Wisconsin-Madison, respectively) suggest that magnetic interactions are what drive the two-fold symmetry—and that they are the key to the superconductivity itself. Perhaps what binds the pairs of electrons together in iron arsenide superconductors is magnetism.

"Orbital theories do not predict a return to four-fold symmetry at this point," Osborn said, "but magnetic models do."

"So far, this effect has only been observed experimentally in these sodium-doped compounds," he said, "but we believe it provides evidence for a magnetic explanation of nematic order in the iron arsenides in general."

It could also affect our understanding of superconductivity in other types of superconductors, such as the copper oxides, where nematic distortions have also been seen, Osborn said.

The paper, titled "Magnetically driven suppression of nematic order in an iron-based superconductor," was published today in Nature Communications.

INFORMATION:

Other coauthors on the paper were Argonne scientists Sevda Avci (now at Afyon Kocatepe University in Turkey), Omar Chmaissem (a joint appointment with Northern Illinois University), Jared M. Allred, Stephan Rosenkranz, Daniel Bugaris, Duck Young Chung, John-Paul Castellan, John Schlueter, Helmut Claus and Mercouri Kanatzidis (a joint appointment with Northwestern University); and Dmitry Khalyavin, Pascal Manuel and Aziz Daoud-Aladine at the ISIS Pulsed Neutron and Muon Source at the Rutherford Appleton Laboratory in Oxfordshire, U.K.

Funding for the research was provided by the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science. The neutron powder diffraction was performed at ISIS.

Argonne National Laboratory seeks solutions to pressing national problems in science and technology. The nation's first national laboratory, Argonne conducts leading-edge basic and applied scientific research in virtually every scientific discipline. Argonne researchers work closely with researchers from hundreds of companies, universities, and federal, state and municipal agencies to help them solve their specific problems, advance America's scientific leadership and prepare the nation for a better future. With employees from more than 60 nations, Argonne is managed by UChicago Argonne, LLC for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science.

DOE's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit science.energy.gov.

Argonne scientists discover new phase in iron-based superconductors

2014-05-23

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Health-care professionals must be aware of rarer causes of headaches in pregnancy

2014-05-23

Most headaches in pregnancy and the postnatal period are benign, but healthcare professionals must be alert to the rarer and more severe causes of headaches, suggests a new review published today (23 May) in The Obstetrician & Gynaecologist (TOG).

The review looks at common causes for headaches during pregnancy and the postnatal period, possible conditions that may be associated with headaches and how healthcare professionals should manage the care of the woman appropriately.

There are 85 different types of headache. Approximately 90% of headaches in pregnancy are migraine ...

A study assesses the possibility of turning CO2 into methanol for use in transport

2014-05-23

Tecnalia has collaborated in a study for the European Parliament's Science and Technology Options Assessment Panel (STOA) on the future use of methanol, produced from carbon dioxide, in motorised transport. STOA is the panel that advises MEPs in the sphere of Science and Technology.

The study analysed the barriers –technological, environmental and economic– to producing methanol using carbon dioxide as well as the options that would allow possible uses in automobile transport in the medium and long term.

The costs and benefits were evaluated from the life cycle perspective ...

New sensor could light the way forward in low-cost medical imaging

2014-05-23

New research published today in Nature's Scientific Reports, identifies a new type of light sensor that could allow medical and security imaging, via low cost cameras.

The team of researchers from the University of Surrey have developed a new 'multispectral' light sensor that detects the full spectrum of light, from ultra-violet (UV), to visible and near infrared light.

Indeed, near infrared light can be used to perform non-invasive medical procedures, such as measuring the oxygen level in tissue and detecting tumours. It is also already commonly used in security camera ...

A new concept to improve power production performance of wind turbines in a wind farm

2014-05-23

Wind energy is one of the most promising renewable energy resources in the world today. Dr. Hui Hu and his group at Iowa State University studied the effects of the relative rotation directions of two tandem wind turbines on the power production performance, the flow characteristics in the turbine wake flows, and the resultant wind loads acting on the turbines. The experimental study was performed in a large-scale Aerodynamics/Atmospheric Boundary Layer (AABL) Wind Tunnel available at Aerospace Engineering Department of Iowa State University. Their work, entitled "An experimental ...

Healthcare professionals must be aware of rarer causes of headaches in pregnancy

2014-05-23

Most headaches in pregnancy and the postnatal period are benign, but healthcare professionals must be alert to the rarer and more severe causes of headaches, suggests a new review published today (23 May) in The Obstetrician & Gynaecologist (TOG).

The review looks at common causes for headaches during pregnancy and the postnatal period, possible conditions that may be associated with headaches and how healthcare professionals should manage the care of the woman appropriately.

There are 85 different types of headache. Approximately 90% of headaches in pregnancy are migraine ...

Yale Cancer Center's tip sheet for the 50th Annual Meeting of ASCO May 30 - June 3, 2014

2014-05-23

The news items below are from oral presentations or poster sessions scheduled for the 50th annual ASCO conference.

Yale Cancer Center will have experts available to speak with the media before or during ASCO.

Survival, response duration, and activity by BRAF mutation (MT) status of nivolumab (NIVO, anti-PD-1, BMS-936558, ONO-4538) and ipilimumab (IPI) concurrent therapy in advanced melanoma (MEL). (LBA #9003)

Authors: Mario Sznol, Harriet M. Kluger, Margaret K. Callahan, Michael Andrew Postow, Ruth Ann Gordon, Neil Howard Segal, Naiyer A. Rizvi, Alexander M. Lesokhin, ...

Parents 'need to be convinced' to let children walk to school

2014-05-23

Parents need to be convinced about the benefits of their children walking or cycling to school as much as the children themselves, according to research led at the University of Strathclyde.

A study of children's habits in commuting to and from school discovered that, in the vast majority of cases, parents were the main decision makers in how the children travelled.

Colder weather in autumn and winter led to a drop in the number of children in an intervention group, who were being encouraged to walk and cycle more, and the control group, who continued their normal ...

Many mental illnesses reduce life expectancy more than heavy smoking

2014-05-23

Serious mental illnesses reduce life expectancy by 10-20 years, an analysis by Oxford University psychiatrists has shown – a loss of years that's equivalent to or worse than that for heavy smoking.

Yet mental health has not seen the same public health priority, say the Oxford scientists, despite these stark figures and the similar prevalence of mental health problems.

1 in 4 people in the UK will experience some kind of mental health problem in the course of a year, it is estimated. Around 21% of British men and 19% of women smoke cigarettes.

The researchers say ...

Study of 850,000 people shows women with diabetes 44 percent more likely to develop coronary heart disease than men with diabetes

2014-05-23

A systematic review and meta-analysis of some 850,000 people published in Diabetologia (the journal of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes) shows that women with diabetes are 44% more likely to develop coronary heart disease (CHD) than men with diabetes independent of sex differences in the levels of other major cardiovascular risk factors. The research is by Professor Rachel Huxley, School of Population Health, University of Queensland,

Australia; Dr Sanne Peters, University of Cambridge, UK, and University Medical Center Utrecht, the Netherlands, and ...

The Lancet: Scientists invent kidney dialysis machine for babies and safely treat newborn with multiple organ failure

2014-05-23

Italian scientists have developed a miniaturised kidney dialysis machine capable of treating the smallest babies, and have for the first time used it to safely treat a newborn baby with multiple organ failure. This technology has the potential to revolutionise the treatment of infants with acute kidney injury, according to new research published in The Lancet.

The new continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) machine—named CARPEDIEM (Cardio-Renal Pediatric Dialysis Emergency Machine)—was created to overcome the problems of existing dialysis machines that are only designed ...