(Press-News.org) Athens, Ga. – The promise of affordable transportation fuels from biomass—a sustainable, carbon neutral route to American energy independence—has been left perpetually on hold by the economics of the conversion process. New research from the University of Georgia has overcome this hurdle allowing the direct conversion of switchgrass to fuel.

The study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, documents the direct conversion of biomass to biofuel without pre-treatment, using the engineered bacterium Caldicellulosiruptor bescii.

Pre-treatment of the biomass feedstock—non-food crops such as switchgrass and miscanthus—is the step of breaking down plant cell walls before fermentation into ethanol. This pre-treatment step has long been the economic bottleneck hindering fuel production from lignocellulosic biomass feedstocks.

Janet Westpheling, a professor in the Franklin College of Arts and Sciences Department of Genetics, and her team of researchers—all members of U.S. Department of Energy-funded BioEnergy Science Center in which UGA is a key partner—succeeded in genetically engineering the organism C. bescii to deconstruct un-pretreated plant biomass.

"Given a choice between teaching an organism how to deconstruct biomass or teaching it how to make ethanol, the more difficult part is deconstructing biomass," said Westpheling, who spent two and a half years developing genetic methods for manipulating the C. bescii bacterium to make the current work possible.

The UGA research group engineered a synthetic pathway into the organism, introducing genes from other anaerobic bacterium that produce ethanol, and constructed a pathway in the organism to produce ethanol directly.

"Now, without any pretreatment, we can simply take switchgrass, grind it up, add a low-cost, minimal salts medium and get ethanol out the other end," Westpheling said. "This is the first step toward an industrial process that is economically feasible."

The recalcitrance of plant biomass for the production of fuels, a resistance to microbial degradation evolved in plants over millions of years, results from their rigid cell walls that have been the key to their survival and the major impediment to biofuel production. Understanding the scientific basis of and ultimately eliminating recalcitrance as a barrier has been the core mission of the BioEnergy Science Center.

"To take a virtually unknown and uncharacterized organism and engineer it to produce a biofuel of choice within the space of a few years is a towering scientific achievement for Dr. Westpheling's group and for BESC," said Paul Gilna, director of the BioEnergy Science Center, headquartered at Oak Ridge National Laboratory. "It is a true reflection of the highly collaborative research we have built within BESC, which, in turn, has led to accelerated accomplishments such as this."

Caldicellulosiruptor bacteria have been isolated around the world—from a hot spring in Russia to Yellowstone National Park. Westpheling explained that many microbes in nature demonstrate prized capabilities in chemistry and biology but that developing the genetic systems to use them is the most significant challenge.

"Systems biology allows for the engineering of artificial pathways into organisms that allow them to do things they cannot do otherwise," she said.

Ethanol is but one of the products the bacterium can be taught to produce. Others include butanol and isobutanol (transportation fuels comparable to ethanol), as well as other fuels and chemicals—using biomass as an alternative to petroleum.

"This is really the beginning of a platform for manipulating organisms to make many products that are truly sustainable," she said.

INFORMATION:

Westpheling's co-authors on the paper are Daehwan Chung and Minseok Cha of the Franklin College department of genetics and Adam M. Guss of the Oak Ridge National Laboratory. All authors are members of the DOE BioEnergy Science Center headquartered at Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Oak Ridge, Tennessee. BESC is a U.S. Department of Energy Bioenergy Research Center supported by the DOE Office of Science.

New UGA research engineers microbes for the direct conversion of biomass to fuel

2014-06-02

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Tracking potato famine pathogen to its home may aid $6 billion global fight

2014-06-02

CORVALLIS, Ore. – The cause of potato late blight and the Great Irish Famine of the 1840s has been tracked to a pretty, alpine valley in central Mexico, which is ringed by mountains and now known to be the ancestral home of one of the most costly and deadly plant diseases in human history.

Research published today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, by researchers from Oregon State University, the USDA Agricultural Research Service and five other institutions, concludes that Phytophthora infestans originated in this valley and co-evolved with potatoes ...

Tumor size is defining factor to response from promising melanoma drug

2014-06-02

CHICAGO — In examining why some advanced melanoma patients respond so well to the experimental immunotherapy MK-3475, while others have a less robust response, researchers at Mayo Clinic in Florida found that the size of tumors before treatment was the strongest variable.

MULTIMEDIA ALERT: Video and audio are available for download on the Mayo Clinic News Network.

They say their findings, being presented June 2 at the 50th annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), offered several clinical insights that could lead to different treatment strategies ...

Anti-diabetic drug slows aging and lengthens lifespan

2014-06-02

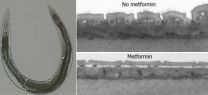

A study by Belgian doctoral researcher Wouter De Haes (KU Leuven) and colleagues provides new evidence that metformin, the world's most widely used anti-diabetic drug, slows ageing and increases lifespan.

In experiments reported in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the researchers tease out the mechanism behind metformin's age-slowing effects: the drug causes an increase in the number of toxic oxygen molecules released in the cell and this, surprisingly, increases cell robustness and longevity in the long term.

Mitochondria – the energy factories ...

Marijuana shows potential in treating autoimmune disease

2014-06-02

A team of University of South Carolina researchers led by Mitzi Nagarkatti, Prakash Nagarkatti and Xiaoming Yang have discovered a novel pathway through which marijuana can suppress the body's immune functions. Their research has been published online in the Journal of Biological Chemistry.

Marijuana is the most frequently used illicit drug in the United States, but as more states legalize the drug for medical and even recreational purposes, research studies like this one are discovering new and innovative potential health applications for the federal Schedule I drug. ...

Shape matters...

2014-06-02

Which look bigger, packages of complicated shape or packages of simple shape? Some prior research shows that complex packages appear larger than simple packages of equal volume, while other research has shown the opposite - that simple packages look bigger than the more complex. US researchers, writing in the International Journal of Management Practice believe they have resolved this dilemma.

Lawrence Garber of Elon University in North Carolina and Eva Hyatt and Ünal Boya of Appalachian State University report that human beings are just not very good at estimating the ...

Carnegie Mellon researchers discover social integration improves lung function in elderly

2014-06-02

PITTSBURGH—It is well established that being involved in more social roles, such as being married, having close friends, close family members, and belonging to social and religious groups, leads to better mental and physical health. However, why social integration — the total number of social roles in which a person participates — influences health and longevity has not been clear.

New research led by Carnegie Mellon University shows for the first time that social integration impacts pulmonary function in the elderly. Lung function, which decreases with age, is an important ...

Study suggests fast food cues hurt ability to savor experience

2014-06-02

Toronto – Want to be able to smell the roses?

You might consider buying into a neighbourhood where there are more sit-down restaurants than fast-food outlets, suggests a new paper from the University of Toronto's Rotman School of Management.

The paper looks at how exposure to fast food can push us to be more impatient and that this can undermine our ability to smell the preverbal roses.

One study, surveyed a few hundred respondents throughout the US on their ability to savor a variety of realistic, enjoyable experiences such as discovering a beautiful waterfall on ...

Gene therapy combined with IMRT found to reduce recurrence for select prostate cancer patients

2014-06-02

Fairfax, Va., June 2, 2014—Combining oncolytic adenovirus-mediated cytotoxic gene therapy (OAMCGT) with intensity modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) reduces the risk of having a positive prostate biopsy two years after treatment in intermediate-risk prostate cancer without affecting patients' quality of life, according to a study published in the June 1, 2014 edition of the International Journal of Radiation Oncology • Biology • Physics (Red Journal), the official scientific journal of the American Society for Radiation Oncology (ASTRO).

Previous prospective ...

How Thomas Edison laid the foundation for the modern lab (video)

2014-06-02

WASHINGTON, June 2, 2014 — Thomas Edison is hands-down one of the greatest inventors in history. He also had a love of chemistry that banished him to the basement as a kid. This week, the Reactions team went behind the scenes at the Thomas Edison National Historical Park to see how Edison's love of chemistry fueled his world-changing inventions. Recently named a National Historic Chemical Landmark, the complex is home to more than 400,000 artifacts (which we definitely weren't allowed to touch) and is considered the template for modern research-and-development labs everywhere. ...

Scientists capture most detailed images yet of humans' tiny cellular machines

2014-06-02

MADISON, Wis. — A grandfather clock is, on its surface, a simple yet elegant machine. Tall and stately, its job is to steadily tick away the time. But a look inside reveals a much more intricate dance of parts, from precisely-fitted gears to cable-embraced pulleys and bobbing levers.

Like exploring the inner workings of a clock, a team of University of Wisconsin-Madison researchers is digging into the inner workings of the tiny cellular machines called spliceosomes, which help make all of the proteins our bodies need to function. In a recent study published in the journal ...