(Press-News.org) When a fruit fly detects an approaching predator, it takes just a fraction of a second to launch itself into the air and soar gracefully to safety—but there's not always time for that. Some threats demand a quicker getaway, even if things get a little clumsy. New research from scientists at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute's Janelia Research Campus reveals how a quick-escape circuit in the fly's brain overrides the fly's slower, more controlled behavior when a threat becomes urgent.

"The fly's rapid takeoff is, on average, eight milliseconds faster than its more controlled takeoff," says Janelia group leader Gwyneth Card. "Eight milliseconds could be the difference between life and death."

Card studies escape behaviors in the fruit fly to unravel the circuits and processes that underlie decision making, teasing out how the brain integrates information to respond to a changing environment. Her team's new study, published online June 8, 2014, in the journal Nature Neuroscience, shows that two neural circuits mediate fruit flies' slow-and-stable or quick-but-clumsy escape behaviors. Card, postdoctoral researcher Catherine von Reyn, and their colleagues find that a spike of activity in a key neuron in the quick-escape circuit can override the slower escape, prompting the fly to spring to safety when a threat gets too near.

A pair of neurons -- called giant fibers -- in the fruit fly brain has long been suspected to trigger escape. Researchers can provoke this behavior by artificially activating the giant fiber neurons, but no one had actually demonstrated that those neurons responded to visual cues associated with an approaching predator, Card says. She was curious how the neurons could be involved in the natural behavior if they didn't seem to respond to the relevant sensory cues, so she decided to test their role.

Genetic tools developed in the lab of Janelia executive director Gerald Rubin enabled Card's team to switch the giant fiber neurons on or off, and then observe how flies responded to a predator-like stimulus. They conducted their experiments in an apparatus developed in Card's lab that captures videos of individual flies as they are exposed to a looming dark circle. The image is projected onto a hemispheric surface and expands rapidly to fill the fly's visual field, simulating the approach of a predator. "It's really like a domed IMAX for the fly," Card explains. A high-speed camera records the response at 6,000 frames per second, allowing Card and her colleagues to examine in detail the series of events that make up the fly's escape.

To ensure their experiments were relevant to fruit flies' real-world experiences, Card teamed with fellow Janelia group leader Anthony Leonardo to record and analyze the trajectories and acceleration of damselflies – natural predators of the fruit fly – as they attacked. They designed their looming stimulus to mimic these features. "We wanted to make sure we were really challenging the animal with something that was like a predator attack," Card says.

By analyzing more than 4,000 flies, Card and her colleagues discovered two distinct responses to the simulated predator: long and short escapes. To prepare for a steady take-off, flies took the time to raise their wings fully. Quicker escapes, in contrast, eliminated this step, shaving time off the take-off but often causing the fly to tumble through the air.

When the scientists switched off the giant fiber neurons, preventing them from firing, flies still managed to complete their escape sequence. "On a surface level evaluation, silencing the neuron had absolutely no effect," Card says. "You can do away with this neuron that people thought was fundamental to this escape behavior, and flies still escape." Shorter escapes, however, were completely eliminated. Flies without active giant fiber neurons invariably opted for the slower, steadier escape. In contrast, when the scientists switched giant fiber neurons on in the absence of a predator-like stimulus, flies enacted their quick-escape behavior. The evidence suggested the giant fiber neurons were involved only in short escapes, while a separate circuit mediated the long escapes.

Card and her colleagues wanted to understand how flies decide when to sacrifice stability in favor of a quicker response. To learn more, Catherine von Reyn, a postdoctoral researcher in Card's lab, set up experiments in which she could directly monitor activity in the giant fiber neurons. Surprisingly, she discovered that the giant fibers were not only active in short-mode escape, but also during some of the long-mode escapes. The situation was more complicated than their genetic experiments had suggested. "Seeing the dynamics of the electrophysiology allowed us to understand that the timing of the spike is important is determining the fly's choice of escape behavior," Card says.

Based on their data, Card and von Reyn propose that a looming stimulus first activates a circuit in the brain that initiates a slow escape, beginning with a controlled lift of the wings. When the object looms closer, filling more of the fly's field of view, the giant fiber activates, prompting a more urgent escape. "What determines whether a fly does a long-mode or a short-mode escape is how soon after the wings go up the fly kicks its legs and it starts to take off," Card says. "The giant fiber can fire at any point during that sequence. It might not fire at all – in which case you get this nice long, beautifully choreographed takeoff. It might fire right away, in which case you get an abbreviated escape." The more quickly an object approaches, the sooner the giant fiber is likely to fire, increasing the probability of a short escape.

Card remains curious about many aspects of escape behavior. How does a fly calculate the orientation of a threat and decide in which direction to flee, she wonders. What makes a fly decide to initiate a takeoff as opposed to other evasive maneuvers? The relatively compact circuits that control these sensory-driven behaviors provide a powerful system for exploring the mechanisms that animals use to selecting one behavior over another, she says. "We think that you can really ask these questions at the level of individual neurons, and even individual spikes in those neurons."

INFORMATION:

Quick getaway: How flies escape looming predators

2014-06-08

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

More than just a hill of beans: Phaseolus genome lends insights into nitrogen fixation

2014-06-08

"It doesn't take much to see that the problems of three little people doesn't add up to a hill of beans in this crazy world," Humphrey Bogart famously said in the movie Casablanca. For the farmers and breeders around the world growing the common bean, however, ensuring that there is an abundant supply of this legume is crucial, both for its importance in cropping systems to ensure plant vitality and for food security. Moreover, the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science has targeted research into the common bean because of its importance in enhancing nitrogen use ...

Argument with dad? Find friendly ears to talk it out, study shows

2014-06-06

With Father's Day approaching, SF State's Jeff Cookston has some advice for creating better harmony with dad. In a recent study, he found that when an adolescent is having an argument with their father and seeks out others for help, the response he or she receives is linked to better well-being and father-child relationships.

Adolescents who receive an reason for the father's behavior or a better understanding of who is at fault feel better about themselves and about dad as well. Those feelings about dad, in turn, are linked to a lower risk of depression for youth.

The ...

Scientists reveal details of calcium 'safety-valve' in cells

2014-06-06

UPTON, NY -- Sometimes a cell has to die-when it's done with its job or inflicted with injury that could otherwise harm an organism. Conversely, cells that refuse to die when expected can lead to cancer. So scientists interested in fighting cancer have been keenly interested in learning the details of "programmed cell death." They want to understand what happens when this process goes awry and identify new targets for anticancer drugs.

The details of one such target have just been identified by a group of scientists from the U.S. Department of Energy's Brookhaven National ...

Brain traffic jams that can disappear in 30 seconds

2014-06-06

BUFFALO, N.Y. – Motorists in Los Angeles, San Francisco and other gridlocked cities could learn something from the fruit fly.

Scientists have found that cellular blockages, the molecular equivalent to traffic jams, in nerve cells of the insect's brain can form and dissolve in 30 seconds or less.

The findings, presented in the journal PLOS ONE, could provide scientists much-needed clues to better identify and treat neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's and Huntington's.

"Our research suggests that fixed, permanent blocks may impede the transport of important ...

LSU biologist John Caprio, Japanese colleagues identify unique way catfish locate prey

2014-06-06

BATON ROUGE – Animals incorporate a number of unique methods for detecting prey, but for the Japanese sea catfish, Plotosus japonicus, it is especially tricky given the dark murky waters where it resides.

John Caprio, George C. Kent Professor of Biological Sciences at LSU, and colleagues from Kagoshima University in Japan have identified that these fish are equipped with sensors that can locate prey by detecting slight changes in the water's pH level.

A paper, "Marine teleost locates live prey through pH sensing," detailing the work of Caprio and his research partners, ...

Better tissue healing with disappearing hydrogels

2014-06-06

When stem cells are used to regenerate bone tissue, many wind up migrating away from the repair site, which disrupts the healing process. But a technique employed by a University of Rochester research team keeps the stem cells in place, resulting in faster and better tissue regeneration. The key, as explained in a paper published in Acta Biomaterialia, is encasing the stem cells in polymers that attract water and disappear when their work is done.

The technique is similar to what has already been used to repair other types of tissue, including cartilage, but had never ...

Lower asthma risk is associated with microbes in infants' homes

2014-06-06

Infants exposed to a diverse range of bacterial species in house dust during the first year of life appear to be less likely to develop asthma in early childhood, according to a new study published online on June 6, 2014, in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology.

Children who were neither allergic nor prone to wheezing as three-year-olds were the most likely to have been exposed to high levels of bacteria, and paradoxically, to high levels of common allergens.

In fact, some of the protective bacteria are abundant in cockroaches and mice, the source of these ...

NASA and NOAA satellites eyeing Mexico's tropical soaker for development

2014-06-06

NASA and NOAA satellites are gathering visible, infrared, microwave and radar data on a persistent tropical low pressure area in the southwestern Bay of Campeche. System 90L now has a 50 percent chance for development, according to the National Hurricane Center and continues to drop large amounts of rainfall over southeastern Mexico.

The Atmospheric Infrared Sounder (AIRS) instrument aboard NASA's Aqua satellite gathered infrared data on the developing low on June 5 at 18:59 UTC (2:59 p.m. EDT).

Basically, AIRS looks at the infrared region of the spectrum. In a spectrum, ...

Study shows health policy researchers lack confidence in social media for communication

2014-06-06

Philadelphia – Though Twitter boats 645 million users across the world, only 14 percent of health policy researchers reported using Twitter – and approximately 20 percent used blogs and Facebook – to communicate their research findings over the past year, according to a new study from the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. In contrast, sixty-five percent used traditional media channels, such as press releases or media interviews. While participants believed that social media can be an effective way to communicate research findings, many lacked ...

Evolution of a bimetallic nanocatalyst

2014-06-06

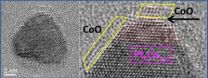

Atomic-scale snapshots of a bimetallic nanoparticle catalyst in action have provided insights that could help improve the industrial process by which fuels and chemicals are synthesized from natural gas, coal or plant biomass. A multi-national lab collaboration led by researchers with the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE)'s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) has taken the most detailed look ever at the evolution of platinum/cobalt bimetallic nanoparticles during reactions in oxygen and hydrogen gases.

"Using in situ aberration-corrected transmission electron ...