(Press-News.org) By studying laboratory mice, scientists at The Johns Hopkins University have succeeded in plotting the labyrinthine paths of some of the largest nerve cells in the mammalian brain: cholinergic neurons, the first cells to degenerate in people with Alzheimer's disease.

"For us, this was like scaling Mount Everest," says Jeremy Nathans, Ph.D., professor of molecular biology and genetics, neuroscience, and ophthalmology at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. "This work reveals the amazing challenges that cholinergic neurons face every day. Each of these cells is like a city connected to its suburbs by a single, one-lane road, with all of the emergency services located only in the city. You can imagine how hard it would be in a crisis if all of the emergency vehicles had to get to the suburbs along that one road. We think something like this might be happening when cholinergic neurons trying to repair the damage done by Alzheimer's disease."

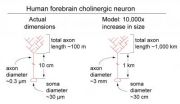

Each cholinergic neuron, Nathans explains, has roughly 1,000 branch points. If lined up end to end, one neuron's branches would add up to approximately 15 times the length of the mouse brain. But all of the branches are connected by a single, extremely thin "pipeline" to one hub — the cell body — that provides for the needs of the branches. The challenge of moving material through this single pipeline could make it very difficult for cholinergic neurons to combat the challenges that come with a disorder like Alzheimer's disease, he says. Now, by mapping the branches and pipelines, scientists will likely get a better fix on what happens when the neurons fail to meet the challenges.

A summary of the research was published online in the journal eLife on May 7.

Cholinergic neurons are among the largest neurons in the mammal brain. Named for their release of a chemical messenger called acetylcholine, they number only in the thousands in mouse brains, a tiny fraction of the 50 to 100 million total neurons. Their cell bodies are located at the base of the brain near its front end, but their branches extend throughout the cerebral cortex, the outermost, wrinkled layer of "grey matter" that is responsible for the mind's most advanced intellectual functions. Therefore, although there are relatively few cholinergic neurons, they affect a very large part of the brain, Nathans says.

Due to the technical challenge of visualizing the complicated paths of hundreds of tiny branches from a single neuron tangled within millions of other neurons, the actual size and shape of individual cholinergic neurons — and the territory they cover — had been unknown until now, Nathans says. Using genetic engineering methods, the Nathans team programmed several cholinergic neurons per mouse to make a protein that could be seen with a colored chemical reaction. Critical to the success of the work was the ability to limit the number of cells making the protein — if all of the cholinergic neurons made the protein, it would have been impossible to distinguish individual branches.

Because microscopes cannot see through thick tissue, Nathans and his team preserved the mouse brains and then thinly sliced them to produce serial images. The branching path of each neuron was then painstakingly reconstructed from the serial images and analyzed. In adult mice, he says, the average length of the branches of a single cholinergic neuron, lined up end to end, is 31 cm (12 inches), varying from 11 to 49 cm (4 to 19 inches). The average length of a mouse brain is only 2 cm — a bit less than one inch. Although each cholinergic neuron, on average, contains approximately 1,000 branch points, they vary significantly in the extent of the territory that they cover.

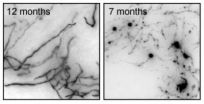

The researchers used the same techniques to study the cholinergic neurons of mice with a rodent form of Alzheimer's disease and found that the branches were fragmented. They also found clumps of material that may have been debris from the disintegrating branches.

Although the cholinergic neurons of human brains have not been individually traced, Nathans' team was able to calculate that the average cholinergic neuron in the human brain has a total branch length of approximately 100 meters, a bit longer than a football field. "That is a really long pipeline, especially if one considers that the pipes have diameters of only 30 thousandths of a millimeter, far narrower than a human hair," says Nathans.

He adds, "Although our study only defined a few simple, physical properties of these neurons, such as size and shape, it has equipped us to form and test better hypotheses about what goes wrong with them during disease."

INFORMATION:

Other authors of the report include Hao Wu and John Williams of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

This work was supported by grants from the Human Frontier Science Program, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and the Brain Science Institute of The Johns Hopkins University.

On the Web:

Link to article in eLife: http://www.dx.doi.org/10.7554/eLife.02444

Nathans Lab: http://nathanslab.mbg.jhmi.edu/

Nathans HHMI Profile: http://www.hhmi.org/scientists/jeremy-nathans

Related stories:

Why Our Backs Can't Read Braille

http://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/news/media/releases/why_our_backs_cant_read_braille

Tangled path of Alzheimer's-linked brain cells mapped in mice

'Transportation' may be at the heart of the disease

2014-06-09

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

NASA's TRMM satellite analyzes Mexico's soaking tropical rains

2014-06-09

VIDEO:

This movie of NOAA's GOES-East satellite imagery shows the movement of System 90L over land and dissipating between June 6 and June 7 at 2000 UTC (4 p.m. EDT)....

Click here for more information.

The movement of tropical storm Boris into southern Mexico and a nearly stationary low pressure system in the southern Gulf of Mexico caused heavy rainfall in that area. NASA and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency's Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission satellite known as TRMM ...

A new methodology developed to monitor traffic flow

2014-06-09

"If we know not only the volume of the traffic but also the way in which the flow is taking place, we can detect when the traffic is undergoing a significant change. This information can be used, for example, when decisions are taken about signs (traffic lights, directions, etc.), road capacity, and other aspects," explained Fermín Mallor, Prof of the Department of Statistics and Operational Research.

What is new about this research is that it applies the so-called curve statistics to the specific problem of traffic control or monitoring. The use of the methodology is ...

NHAES research: New England lakes recovering rapidly from acid rain

2014-06-09

DURHAM, N.H. – For more than 40 years, policy makers have been working to reduce acid rain, a serious environmental problem that can devastate lakes, streams, and forests and the plants and animals that live in these ecosystems. Now new research funded by the NH Agricultural Experiment Station (NHAES) at the University of New Hampshire College of Life Sciences and Agriculture indicates that lakes in New England and the Adirondack Mountains are recovering rapidly from the effects of acid rain.

Researchers found that sulfate concentration in rain and snow declined by more ...

Angry faces back up verbal threats, making them seem more credible

2014-06-09

We've all been on the receiving end of an angry glare, whether from a teacher, parent, boss, or significant other. These angry expressions seem to boost the effectiveness of threats without actual aggression, according to research published in Psychological Science, a journal of the Association for Psychological Science.

The research findings show that angry expressions lend additional weight to a negotiator's threat to walk away from the table if his or her demands aren't met, leading the other party in the negotiation to offer more money than they otherwise would have.

"Our ...

Distance from a conflict may promote wiser reasoning

2014-06-09

If you're faced with a troubling personal dilemma, such as a cheating spouse, you may think about it more wisely if you consider it as an outside observer would, according to research forthcoming in Psychological Science, a journal of the Association for Psychological Science.

"These results are the first to demonstrate a new type of bias within ourselves when it comes to wise reasoning about an interpersonal relationship dilemma," says psychology researcher and study author Igor Grossmann of the University of Waterloo in Canada. "We call the bias Solomon's Paradox, ...

Penn Medicine at the International Congress of Parkinson's Disease and Movement Disorders

2014-06-09

Penn Medicine researchers will be among the featured presenters at the 18th International Congress of Parkinson's Disease and Movement Disorders in Stockholm, Sweden, from Sunday, June 8 to Thursday, June 12, 2014.

Matthew Stern, MD, director of the Parkinson's Disease and Movement Disorders Center in the Department of Neurology and current president of the International Parkinson's Disease and Movement Disorders Society, will chair a plenary session entitled "New insights into the pathology, progression, and heterogeneity of Parkinson's disease."

John Q. Trojanowski, ...

What causes garlic breath? (video)

2014-06-09

WASHINGTON, June 9, 2014 — Garlic is good for your body, great for your taste buds, but terrible for your breath. In the American Chemical Society's latest Reactions video, we look at the plant beloved by chefs and feared by vampires. Once again we teamed up with the Compound Interest blog to break down the chemistry of garlic, and how to beat the bad breath it causes. The video is available at http://youtu.be/cAWLQ_4DphI.

INFORMATION:

Subscribe to the series at Reactions YouTube, and follow us on Twitter @ACSreactions to be the first to see our latest videos.

The ...

Health Affairs asks: Where can we find savings in health care?

2014-06-09

Reducing Maternal Mortality In Zambia and Uganda. Margaret E. Kruk of Columbia University and co-authors assessed the effectiveness of Saving Mothers, Giving Life, a new global public-private partnership that aims to reduce maternal mortality in eight districts in Uganda and Zambia. They evaluated the first six to twelve months of the program's implementation, its ownership by national ministries of health, and its effects on health systems. According to the authors, early benefits to the broader health system included greater policy attention to maternal and child health, ...

Common bean genome sequence provides powerful tools to improve critical food crop

2014-06-09

Huntsville, Ala. – String bean, snap bean, haricot bean, and pinto and navy bean. These are just a few members of the common bean family — scientifically called Phaseolus vulgaris. These beans are critically important to the global food supply. They provide up to 15 percent of calories and 36 percent of daily protein for parts of Africa and the Americas and serve as a daily staple for hundreds of millions of people.

Now, an international collaboration of researchers, led by Jeremy Schmutz of the HudsonAlpha Institute for Biotechnology and Phillip McClean, of North Dakota ...

Sequencing of citrus genomes points to need for more genetic diversity to fight disease

2014-06-09

Huntsville, Ala. – Sequencing the genomes of domesticated citrus revealed a very limited genetic diversity that could threaten the crop's survival prospects, according to an international research team. In a study published in the June issue of Nature Biotechnology, the international consortium of researchers from the United States, France, Italy, Spain and Brazil analyzed and compared the genome sequences of 10 diverse citrus varieties, including sweet and sour orange along with several important mandarin and pummelo cultivars. The findings provide the clearest insight ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Kidney cancer study finds belzutifan plus pembrolizumab post-surgery helps patients at high risk for relapse stay cancer-free longer

Alkali cation effects in electrochemical carbon dioxide reduction

Test platforms for charging wireless cars now fit on a bench

$3 million NIH grant funds national study of Medicare Advantage’s benefit expansion into social supports

Amplified Sciences achieves CAP accreditation for cutting-edge diagnostic lab

Fred Hutch announces 12 recipients of the annual Harold M. Weintraub Graduate Student Award

Native forest litter helps rebuild soil life in post-mining landscapes

Mountain soils in arid regions may emit more greenhouse gas as climate shifts, new study finds

Pairing biochar with other soil amendments could unlock stronger gains in soil health

Why do we get a skip in our step when we’re happy? Thank dopamine

UC Irvine scientists uncover cellular mechanism behind muscle repair

Platform to map living brain noninvasively takes next big step

Stress-testing the Cascadia Subduction Zone reveals variability that could impact how earthquakes spread

We may be underestimating the true carbon cost of northern wildfires

Blood test predicts which bladder cancer patients may safely skip surgery

Kennesaw State's Vijay Anand honored as National Academy of Inventors Senior Member

Recovery from whaling reveals the role of age in Humpback reproduction

Can the canny tick help prevent disease like MS and cancer?

Newcomer children show lower rates of emergency department use for non‑urgent conditions, study finds

Cognitive and neuropsychiatric function in former American football players

From trash to climate tech: rubber gloves find new life as carbon capturers materials

A step towards needed treatments for hantaviruses in new molecular map

Boys are more motivated, while girls are more compassionate?

Study identifies opposing roles for IL6 and IL6R in long-term mortality

AI accurately spots medical disorder from privacy-conscious hand images

Transient Pauli blocking for broadband ultrafast optical switching

Political polarization can spur CO2 emissions, stymie climate action

Researchers develop new strategy for improving inverted perovskite solar cells

Yes! The role of YAP and CTGF as potential therapeutic targets for preventing severe liver disease

Pancreatic cancer may begin hiding from the immune system earlier than we thought

[Press-News.org] Tangled path of Alzheimer's-linked brain cells mapped in mice'Transportation' may be at the heart of the disease