(Press-News.org) On the island of Java, in Indonesia, the silvery gibbon, an endangered primate, lives in the rainforests. In a behavior that's unusual for a primate, the silvery gibbon sings: It can vocalize long, complicated songs, using 14 different note types, that signal territory and send messages to potential mates and family.

Far from being a mere curiosity, the silvery gibbon may hold clues to the development of language in humans. In a newly published paper, two MIT professors assert that by re-examining contemporary human language, we can see indications of how human communication could have evolved from the systems underlying the older communication modes of birds and other primates.

From birds, the researchers say, we derived the melodic part of our language, and from other primates, the pragmatic, content-carrying parts of speech. Sometime within the last 100,000 years, those capacities fused into roughly the form of human language that we know today.

But how? Other animals, it appears, have finite sets of things they can express; human language is unique in allowing for an infinite set of new meanings. What allowed unbounded human language to evolve from bounded language systems?

"How did human language arise? It's far enough in the past that we can't just go back and figure it out directly," says linguist Shigeru Miyagawa, the Kochi-Manjiro Professor of Japanese Language and Culture at MIT. "The best we can do is come up with a theory that is broadly compatible with what we know about human language and other similar systems in nature."

Specifically, Miyagawa and his co-authors think that some apparently infinite qualities of modern human language, when reanalyzed, actually display the finite qualities of languages of other animals — meaning that human communication is more similar to that of other animals than we generally realized.

"Yes, human language is unique, but if you take it apart in the right way, the two parts we identify are in fact of a finite state," Miyagawa says. "Those two components have antecedents in the animal world. According to our hypothesis, they came together uniquely in human language."

Introducing the 'integration hypothesis'

The current paper, "The Integration Hypothesis of Human Language Evolution and the Nature of Contemporary Languages," is published this week in Frontiers in Psychology. The authors are Miyagawa; Robert Berwick, a professor of computational linguistics and computer science and engineering in MIT's Laboratory for Information and Decision Systems; and Shiro Ojima and Kazuo Okanoya, scholars at the University of Tokyo.

The paper's conclusions build on past work by Miyagawa, which holds that human language consists of two distinct layers: the expressive layer, which relates to the mutable structure of sentences, and the lexical layer, where the core content of a sentence resides. That idea, in turn, is based on previous work by linguistics scholars including Noam Chomsky, Kenneth Hale, and Samuel Jay Keyser.

The expressive layer and lexical layer have antecedents, the researchers believe, in the languages of birds and other mammals, respectively. For instance, in another paper published last year, Miyagawa, Berwick, and Okanoya presented a broader case for the connection between the expressive layer of human language and birdsong, including similarities in melody and range of beat patterns.

Birds, however, have a limited number of melodies they can sing or recombine, and nonhuman primates have a limited number of sounds they make with particular meanings. That would seem to present a challenge to the idea that human language could have derived from those modes of communication, given the seemingly infinite expression possibilities of humans.

But the researchers think certain parts of human language actually reveal finite-state operations that may be linked to our ancestral past. Consider a linguistic phenomenon known as "discontiguous word formation," which involve sequences formed using the prefix "anti," such as "antimissile missile," or "anti-antimissile missile missile," and so on. Some linguists have argued that this kind of construction reveals the infinite nature of human language, since the term "antimissile" can continually be embedded in the middle of the phrase.

However, as the researchers state in the new paper, "This is not the correct analysis." The word "antimissile" is actually a modifier, meaning that as the phrase grows larger, "each successive expansion forms via strict adjacency." That means the construction consists of discrete units of language. In this case and others, Miyagawa says, humans use "finite-state" components to build out their communications.

The complexity of such language formations, Berwick observes, "doesn't occur in birdsong, and doesn't occur anywhere else, as far as we can tell, in the rest of the animal kingdom." Indeed, he adds, "As we find more evidence that other animals don't seem to posses this kind of system, it bolsters our case for saying these two elements were brought together in humans."

An inherent capacity

To be sure, the researchers acknowledge, their hypothesis is a work in progress. After all, Charles Darwin and others have explored the connection between birdsong and human language. Now, Miyagawa says, the researchers think that "the relationship is between birdsong and the expression system," with the lexical component of language having come from primates. Indeed, as the paper notes, the most recent common ancestor between birds and humans appears to have existed about 300 million years ago, so there would almost have to be an indirect connection via older primates — even possibly the silvery gibbon.

As Berwick notes, researchers are still exploring how these two modes could have merged in humans, but the general concept of new functions developing from existing building blocks is a familiar one in evolution.

"You have these two pieces," Berwick says. "You put them together and something novel emerges. We can't go back with a time machine and see what happened, but we think that's the basic story we're seeing with language."

Miyagawa acknowledges that research and discussion in the field will continue, but says he hopes colleagues will engage with the integration hypothesis.

"It's worthy of being considered, and then potentially challenged," Miyagawa says.

INFORMATION:

Related Links

ARCHIVE: How human language could have evolved from birdsong

http://newsoffice.mit.edu/2013/how-human-language-could-have-evolved-from-birdsong-0221

ARCHIVE: Unique languages, universal patterns

http://newsoffice.mit.edu/2012/unique-universal-languages-0223

ARCHIVE: MIT Libraries receive papers of distinguished linguist, philosopher and activist Noam Chomsky

http://newsoffice.mit.edu/2012/libraries-chomsky-collection-0209

New paper amplifies hypothesis on human language's deep origins

Amplifies hypothesis that human language builds on birdsong and speech forms of other primates

2014-06-11

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

A common hypertension treatment may reduce PTSD symptoms

2014-06-11

Philadelphia, PA, June 11, 2014 – There are currently only two FDA-approved medications for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in the United States. Both of these medications are serotonin uptake inhibitors. Despite the availability of these medications, many people diagnosed with PTSD remain symptomatic, highlighting the need for new medications for PTSD treatment.

The renin-angiotensin system has long been of interest to psychiatry. Some of the first drugs targeting this system were the angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin ...

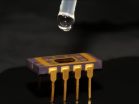

Chemical sensor on a chip

2014-06-11

This news release is available in German. They are invisible, but perfectly suited for analysing liquids and gases; infrared laser beams are absorbed differently by different molecules. This effect can for instance be used to measure the oxygen concentration in blood. At the Vienna University of Technology, this technique has now been miniaturized and implemented in the prototype for a new kind of sensor.

Specially designed quantum cascade lasers and light detectors are created by the same production process. The gap between laser and detector is only 50 micrometres. ...

Eye evolution: A snapshot in time

2014-06-11

This news release is available in German. Larvae of the marine bristle worm Platynereis dumerilii orient themselves using light. Early in their development, these larvae swim towards the light to use surface currents for their dispersal. Older larvae turn away from the light and swim to the sea floor where they develop into adult worms. Scientists of the Max Planck Institute for Developmental Biology in Tübingen have discovered that this change in the behavioural response to light is coupled to different neuronal systems underlying the eyes. The scientists have reconstructed ...

Foaling mares are totally relaxed -- no stress

2014-06-11

Foaling in horses is extremely fast. Labour and the active part of foaling, resulting in delivery of the foal, take 10 to 20 minutes and are considerably shorter than giving birth in humans or in cows. Is this brief period stressful for the animals or are horses more relaxed than humans when giving birth? This issue has been addressed by Christina Nagel and colleagues, who closely observed 17 foalings at the Brandenburg State Stud in Neustadt (Dosse), Germany, as well as recording electrocardiograms before, during and after foaling. The researchers also took samples of ...

Making new species without sex

2014-06-11

This news release is available in German. Occasionally, two different plant species interbreed with each other in nature. This usually causes problems since the genetic information of both parents does not match. But sometimes nature uses a trick. Instead of passing on only half of each parent's genetic material, both plants transmit the complete information to the next generation. This means that the chromosome sets are totted up. The chromosomes are then able to find their suitable partner during meiosis, a type of cell division that produces an organism's reproductive ...

Having authoritarian parents increases the risk of drug use in adolescents

2014-06-11

Alcohol, tobacco and cannabis use is very widespread among youths in Spain compared to the majority of European countries, according to the latest data from the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction.

An international team, led by the European Institute of Studies on Prevention (IREFREA) with headquarters in Mallorca, together with other European and Spanish universities (Oviedo, Santiago de Compostela and Valencia), has analysed the role that parents play at the time of determining the risk of their children using alcohol, tobacco and cannabis in six ...

Herpes infected humans before they were human

2014-06-11

Researchers at the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine have identified the evolutionary origins of human herpes simplex virus (HSV) -1 and -2, reporting that the former infected hominids before their evolutionary split from chimpanzees 6 million years ago while the latter jumped from ancient chimpanzees to ancestors of modern humans – Homo erectus – approximately 1.6 million years ago.

The findings are published in the June 10 online issue of Molecular Biology and Evolution.

"The results help us to better understand how these viruses evolved and found ...

Canadian physicians lack knowledge and confidence about breastfeeding

2014-06-11

OTTAWA, Ontario – June 11, 2014 –The results of a national research project to assess breastfeeding knowledge, confidence, beliefs, and attitudes of Canadian physicians are available today in the Journal of Human Lactation.

"Physicians' attitudes and recommendations are known to directly impact the duration that a mom breastfeeds," said Dr. Catherine Pound, pediatrician and lead author of the study at the Children's Hospital of Eastern Ontario (CHEO). "Worldwide healthcare organizations readily promote the benefits of breastfeeding, and yet now we find a gap exists where ...

Researchers identify regulation process of protein linked to bipolar disorder

2014-06-11

BOSTON (June 11, 2014) — Researchers from Tufts have gained new insight into a protein associated with bipolar disorder. The study, published in the June 3 issue of Science Signaling, reveals that calcium channels in resting neurons activate the breakdown of Sp4, which belongs to a class of proteins called transcription factors that regulate gene expression.

This study, led by Grace Gill, identifies a molecular mechanism regulating Sp4 activity. Her previous research had determined that reduced levels of Sp4 in the brain are associated with bipolar disorder. Her work ...

DNA-linked nanoparticles form switchable 'thin films' on a liquid surface

2014-06-11

UPTON, NY—Scientists seeking ways to engineer the assembly of tiny particles measuring just billionths of a meter have achieved a new first—the formation of a single layer of nanoparticles on a liquid surface where the properties of the layer can be easily switched. Understanding the assembly of such nanostructured thin films could lead to the design of new kinds of filters or membranes with a variable mechanical response for a wide range of applications. In addition, because the scientists used tiny synthetic strands of DNA to hold the nanoparticles together, the study ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

New study reveals how a key receptor tells apart two nearly identical drug molecules

Parkinson’s disease triggers a hidden shift in how the body produces energy

Eleven genetic variants affect gut microbiome

Study creates most precise map yet of agricultural emissions, charts path to reduce hotspots

When heat flows like water

Study confirms Arctic peatlands are expanding

KRICT develops microfluidic chip for one-step detection of PFAs and other pollutants

How much can an autonomous robotic arm feel like part of the body

Cell and gene therapy across 35 years

Rapid microwave method creates high performance carbon material for carbon dioxide capture

New fluorescent strategy could unlock the hidden life cycle of microplastics inside living organisms

HKUST develops novel calcium-ion battery technology enhancing energy storage efficiency and sustainability

High-risk pregnancy specialists present research on AI models that could predict pregnancy complications

Academic pressure linked to increased risk of depression risk in teens

Beyond the Fitbit: Why your next health tracker might be a button on your shirt

UCSB scientists bottle the sun with liquid battery

Lung cancer drug offers a surprising new treatment against ovarian cancer

When consent meets reality: How young men navigate intimacy

Siemens Healthineers and Mayo Clinic expand strategic collaboration to enhance patient care through advanced technology

Physicists develop new protocol for building photonic graph states

OHSU-led research initiative examines supervised psilocybin

New review identifies pathways for managing PFAS waste in semiconductor manufacturing

New research finds state-level abortion restrictions associated with increased maternal deaths

New study assesses potential dust control options for Great Salt Lake

Science policy education should start on campus

Look again! Those wrinkly rocks may actually be a fossilized microbial community

Exposure to intense wildfire smoke during pregnancy may be linked to increased likelihood of autism

Children with Crohn’s have distinct gut bacteria from kids with other digestive disorders

Genomics offers a faster path to restoring the American chestnut

Caught in the act: Astronomers watch a vanishing star turn into a black hole

[Press-News.org] New paper amplifies hypothesis on human language's deep originsAmplifies hypothesis that human language builds on birdsong and speech forms of other primates