(Press-News.org) A new study from Karolinska Institutet in Sweden shows that a part of the nervous system, the parasympathetic nervous system, is formed in a way that is different from what researchers previously believed. In this study, which is published in the journal Science, a new phenomenon is investigated within the field of developmental biology, and the findings may lead to new medical treatments for congenital disorders of the nervous system.

Almost all of the body's functions are controlled by the autonomous, involuntary nervous system, for example the heart and blood vessels, liver and gastrointestinal system. At rest, the body is set up for energy saving functions, which is regulated by the parasympathetic part of the autonomous nervous system. Current understanding is that many important types of cells, including the parasympathetic nerve cells in various organs, originate in early progenitor cells that move short distances while the embryo is still small. But this model does not explain how many of our organs – which develop relatively late, when the embryo is large – are furnished with cells that form the parasympathetic neurons.

This study alters a fundamental principal of our understanding of how the peripheral nervous system develops in the body. Researchers at Karolinska Institutet have made three-dimensional reconstructions of mouse embryos. These show that the parasympathetic neurons are formed from immature glial cells known as Schwann cell precursors that travel along the peripheral nerves out to the body's tissues and organs. The immature cells have the properties of stem cells and may be the origin of several different types of cells. For example, the researchers behind this new study have previously demonstrated that the majority of our melanocytes (pigment cells) are born from these cells.

"Our study focuses on a new principal of developmental biology, a targeted recruitment of cells that are probably also used in the reconstruction of tissue. Despite the elegance, simplicity and beauty of this principal, it is still unclear how the number of parasympathetic neurons is controlled and why only some of the cells transported by nerves are transformed into that which becomes an important part of the nervous system", says Igor Adameyko at the Department of Physiology and Pharmacology who, together with Patrik Ernfors at the Department of Medical Biochemistry and Biophysics, is responsible for the study.

Somewhat surprisingly, the researchers found that the entire parasympathetic nervous system arises from these progenitor cells that travel along the peripheral nerves. The researchers hope that this discovery will open up the possibility of new ways to treat congenital disorders of the autonomous nervous system using regenerative medicine.

INFORMATION:

The study has been financed with funds from, among others, the Swedish Research Council, the Swedish Cancer Society, the European Research Council and Hjärnfonden.

Publication: "Parasympathetic neurons originate from nerve-associated peripheral glial progenitors", Vyacheslav Dyachuk, Alessandro Furlan, Maryam Khatibi Shahidi, Marcela, Giovenco, Nina Kaukua, Chrysoula Konstantinidou, Vassilis Pachnis, Fatima Memic, Ulrika Marklund, Thomas Müller, Carmen Birchmeier, Kaj Fried, Patrik Ernfors, and Igor Adameyko, Science online 12 June 2014.

Contact the Press Office and download images: ki.se/pressroom

Karolinska Institutet - a medical university: ki.se/english

Unexpected origin for important parts of the nervous system

2014-06-12

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Scientists discover link between climate change and ocean currents over 6 million years

2014-06-12

Scientists have discovered a relationship between climate change and ocean currents over the past six million years after analysing an area of the Atlantic near the Strait of Gibraltar, according to research published today (Friday, 13 June) in the journal Science.

An expedition of scientists, jointly led by Dr Javier Hernandez-Molina, from the Department of Earth Sciences at Royal Holloway, University of London, examined core samples from the seabed off the coast of Spain and Portugal which provided proof of shifts of climate change over millions of years.

The team ...

Habitat fragmentation increases vulnerability to disease in wild plants

2014-06-12

Proximity to other meadows increases disease resistance in wild meadow plants, according to a study led by Anna-Liisa Laine at the University of Helsinki. The results of the study, analysing the epidemiological dynamics of a fungal pathogen in the archipelago of Finland, will be published in Science on 13 June 2014.

The study surveyed more than 4,000 Plantago lanceolata meadows and their infection status by a powdery mildew fungus in the Åland archipelago of Finland. The surveys have continued since 2001, resulting in one of the world's largest databases on disease dynamics ...

Quantum computation: Fragile yet error-free

2014-06-12

This news release is available in German and Spanish. Even computers are error-prone. The slightest disturbances may alter saved information and falsify the results of calculations. To overcome these problems, computers use specific routines to continuously detect and correct errors. This also holds true for a future quantum computer, which will require procedures for error correction as well: "Quantum phenomena are extremely fragile and error-prone. Errors can spread rapidly and severely disturb the computer," says Thomas Monz, member of Rainer Blatt's research group ...

Movies with gory and disgusting scenes more likely to capture and engage audience

2014-06-12

Washington, DC (June 12, 2014) – We know it too well. We are watching a horror film and the antagonist is about to maim a character; we ball up, get ready for the shot and instead of turning away, we lean forward in the chair, then flinch and cover our eyes – Jason strikes again! But what is going on in our body that drives us to this reaction, and why do we engage in it so readily? Recent research published in the Journal of Communication found that people exposed to core disgusts (blood, guts, body products) showed higher levels of attention the more disgusting the content ...

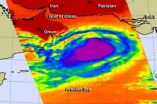

NASA takes Tropical Cyclone Nanuak's temperature

2014-06-12

Tropical Cyclone Nanauk is holding its own for now as it moves through the Arabian Sea. NASA's Aqua satellite took its cloud top temperatures to determine its health.

In terms of infrared data viewing tropical cyclones, those with the coldest cloud top temperatures indicate that a storm is the most healthy, most robust and powerful. That's because thunderstorms that have strong uplift are pushed to the top of the troposphere where temperatures are bitter cold. Infrared data, such as that collected from the Atmospheric Infrared Sounder (AIRS) instrument that flies aboard ...

Findings point toward one of first therapies for Lou Gehrig's disease

2014-06-12

CORVALLIS, Ore. – Researchers have determined that a copper compound known for decades may form the basis for a therapy for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), or Lou Gehrig's disease.

In a new study just published in the Journal of Neuroscience, scientists from Australia, the United States (Oregon), and the United Kingdom showed in laboratory animal tests that oral intake of this compound significantly extended the lifespan and improved the locomotor function of transgenic mice that are genetically engineered to develop this debilitating and terminal disease.

In humans, ...

Scientists identify Deepwater Horizon Oil on shore even years later, after most has degraded

2014-06-12

Years after the 2010 Deepwater Horizon Oil spill, oil continues to wash ashore as oil-soaked "sand patties," persists in salt marshes abutting the Gulf of Mexico, and questions remain about how much oil has been deposited on the seafloor. Scientists from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences have developed a unique way to fingerprint oil, even after most of it has degraded, and to assess how it changes over time. Researchers refined methods typically used to identify the source of oil spills and adapted them for application on a ...

Anti-dsDNA, surface-expressed TLR4 and endosomal TLR9 cooperate to exacerbate lupus

2014-06-12

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a complicated multifactorial autoimmune disease influenced by many genetic and environmental factors. The hallmark of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is the presence of high levels of anti-double-stranded DNA autoantibody (anti-dsDNA) in sera. In addition, greater infection rates are found in SLE patients and higher morbidity and mortality usually come from bacterial infections. Deciphering interactions between the susceptibility genes and the environmental factors for lupus complex traits is challenging and has resulted in only ...

Protein anchors help keep embryonic development 'just right'

2014-06-12

The "Goldilocks effect" in fruit fly embryos may be more intricate than previously thought. It's been known that specific proteins, called histones, must exist within a certain range—if there are too few, a fruit fly's DNA is damaged; if there are too many, the cell dies. Now research out of the University of Rochester shows that different types of histone proteins also need to exist in specific proportions. The work further shows that cellular storage facilities keep over-produced histones in reserve until they are needed.

Associate Professor of Biology Michael Welte ...

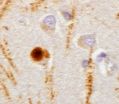

Penn study describes new models for testing Parkinson's disease immune-based drugs

2014-06-12

PHILADELPHIA - Using powerful, newly developed cell culture and mouse models of sporadic Parkinson's disease (PD), a team of researchers from the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, has demonstrated that immunotherapy with specifically targeted antibodies may block the development and spread of PD pathology in the brain. By intercepting the distorted and misfolded alpha-synuclein (α-syn) proteins that enter and propagate in neurons, creating aggregates, the researchers prevented the development of pathology and also reversed some of the ...