(Press-News.org) DURHAM, N.C. -- A team of scientists from Duke Medicine, the University of Michigan and Stanford University has determined the underlying architecture of a cellular signaling complex involved in the body's response to stimuli such as light and pain.

This complex, consisting of a human cell surface receptor and its regulatory protein, reveals a two-step mechanism that has been hypothesized previously but not directly documented.

The findings, reported on June 22, 2014, in the journal Nature, provide structural images of a G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR) in action.

"It is crucial to visualize how these receptors work to fully appreciate how our bodies respond to a wide array of stimuli, including light, hormones and various chemicals," said co-senior author Robert J. Lefkowitz, M.D., the James B. Duke Professor of Medicine at Duke University School of Medicine and Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator.

Lefkowitz is co-senior author with Georgios Skiniotis, Ph.D., the Jack E. Dixon Collegiate Professor at the Life Sciences Institute at the University of Michigan, and Brian K. Kobilka, M.D., the Helene Irwin Fagan Chair in Cardiology at Stanford University School of Medicine. Lefkowitz and Kobilka shared the 2012 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for their discoveries involving GPCRs.

GPCRs represent the largest family of drug targets for human diseases, including cardiovascular disorders, neurological ailments and various types of cancer. The protein beta arrestin is key for regulating these receptors, and the authors have visualized a complex of the protein beta arrestin along with the receptor involved in the "fight-or-flight" response in humans.

"Arrestin's primary role is to put the cap on GPCR signaling. Elucidating the structure of this complex is crucial for understanding how the receptors are desensitized in order to prevent aberrant signaling," Skiniotis said.

"High-resolution visualization of this signaling assembly is challenging because the protein complexes are transient and highly dynamic and large amounts of the isolated proteins are required for the experiments," said co-lead author Arun K. Shukla, who worked with Lefkowitz at Duke and is now setting up an independent laboratory in the Department of Biological Sciences and Bioengineering at the Indian Institute of Technology, Kanpur.

Once the authors had material available for direct structural visualization, they used electron microscopy to reveal how the individual molecules of this signaling assembly are organized with respect to each other.

The researchers then combined thousands of individual images to generate a better picture of the molecular architecture. They further clarified this picture by cross-linking analysis and mass spectrometry measurements.

The authors next aim to obtain greater detail about this assembly using X-ray crystallography, a technology that should reveal atomic level insights into this architecture. Such atomic details could then be used in experiments to design novel drugs and develop a better understanding of fundamental concepts in GPCR biology.

"This is just a start and there is a long way to go," Shukla said. "We have to visualize similar complexes of other GPCRs to develop a comprehensive understanding of this family of receptors."

In addition to Lefkowitz, Shukla, Skiniotis and Kobilka, study authors include Gerwin H. Westfield; Kunhong Xiao; Rosana I. Reis; Li-Yin Huang; Prachi Tripathi-Shukla; Jiang Qian; Sheng Li; Adi Blanc; Austin N. Oleskie; Anne M. Dosey; Min Su; Cui-Rong Liang; Ling-Ling Gu; Jin-Ming Shan; Xin Chen; Rachel Hanna; Minjung Choi; Xiao Jie Yao; Bjoern U. Klink; Alem W. Kahsai; Sachdev S. Sidhu; Shohei Koide; Pawel A. Penczek; Anthony A. Kossiakoff; and Virgil L. Woods Jr.

Howard Hughes Medical Institute provided funding, along with the National Institutes of Health (DK090165, NS028471, GM072688, GM087519, HL075443, HL16037 and HL70631); the Mathers Foundation; the Pew Scholars Program in Biomedical Sciences; the Canadian Institutes of Health Research; and Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior–CAPES.

INFORMATION:

Architecture of signaling proteins enhances knowledge of key receptors

2014-06-22

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Study shows greater potential for solar power

2014-06-22

Concentrating solar power (CSP) could supply a large fraction of the power supply in a decarbonized energy system, shows a new study of the technology and its potential practical application.

Concentrating solar power (CSP) could supply a substantial amount of current energy demand, according to the study published in the journal Nature Climate Change. In the Mediterranean region, for example, the study shows that a connected CSP system could provide 70-80% of current electricity demand, at no extra cost compared to gas-fired power plants. That percentage is similar to ...

Microenvironment of hematopoietic stem cells can be a target for myeloproliferative disorders

2014-06-22

The discovery of a new therapeutic target for certain kinds of myeloproliferative disease is, without doubt, good news. This is precisely the discovery made by the Stem Cell Physiopathology group at the CNIC (the Spanish National Cardiovascular Research Center), led by Dr. Simón Méndez–Ferrer. The team has shown that the microenvironment that controls hematopoietic stem cells can be targeted for the treatment of a set of disorders called myeloproliferative neoplasias, the most prominent of which are chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML), juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia ...

Family of proteins plays key role in cellular pump dynamics

2014-06-22

Case Western Reserve University scientists have discovered how a family of proteins — cation diffusion facilitators (CDFs) — regulates an important cellular cycle where a cell's energy generated is converted to necessary cellular functions. The finding has the potential to inform future research aimed at identifying ways to ensure the process works as designed and, if successful, could lead to significant breakthroughs in the treatment of Parkinson's, chronic liver disease and heart disease.

The results of this research were posted online June 22 by the journal Nature ...

Evidence found for the Higgs boson direct decay into fermions

2014-06-22

For the first time, scientists from the CMS experiment on the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN have succeeded in finding evidence for the direct decay of the Higgs boson into fermions. Previously, the Higgs particle could only be detected through its decay into bosons. "This is a major step forwards," explains Professor Vincenzo Chiochia from the University of Zurich's Physics Institute, whose group was involved in analyzing the data. "We now know that the Higgs particle can decay into both bosons and fermions, which means we can exclude certain theories predicting that ...

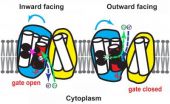

Protons power protein portal to push zinc out of cells

2014-06-22

Researchers at The Johns Hopkins University report they have deciphered the inner workings of a protein called YiiP that prevents the lethal buildup of zinc inside bacteria. They say understanding YiiP's movements will help in the design of drugs aimed at modifying the behavior of ZnT proteins, eight human proteins that are similar to YiiP, which play important roles in hormone secretion and in signaling between neurons.

Certain mutations in one of them, ZnT8, have been associated with an increased susceptibility to type 2 diabetes, but mutations that destroy its function ...

Molecular footballs could revolutionize your next World Cup experience!

2014-06-22

This work focuses on the interactions between molecules and in particular on "amphiphilic" molecules, which contain two distinct parts to them. Household detergent is a good example of a product that relies on interacting amphiphilic molecules. Detergent molecules comprise two distinct parts: one that prefers to form bonds with water (hydrophilic) and the other that likes oily substances (hydrophobic). Detergents are used for cleaning because when they are added to dirty water, they orient and assemble around oily dirt, forming small clusters that allow grease and dirt ...

Antidepressant use during pregnancy may lead to childhood obesity and diabetes

2014-06-21

Hamilton, ON (June 21, 2014) - Women who take antidepressants during pregnancy may be unknowingly predisposing their infants to type 2 diabetes and obesity later in life, according to new research from McMaster University.

The study finds a correlation between the use of the medication fluoxetine

during pregnancy and an increased risk of obesity and diabetes in children.

Currently, up to 20 per cent of woman in the United States and approximately seven per cent of Canadian women are prescribed an antidepressant during pregnancy.

"Obesity and Type 2 diabetes in ...

Church-going is not enough to affect job satisfaction and commitment, Baylor study finds

2014-06-20

A congregation's beliefs about work attitudes and practices affect a churchgoer on the job — but how much depends in part on how involved that person is in the congregation, according to a Baylor University study funded by the National Science Foundation.

"We already knew that about 60 percent of American adults are affiliated with congregations, but we wanted to delve into whether that carries over from weekend worship services to the work day," said Jerry Z. Park, Ph.D., associate professor of sociology in Baylor's College of Arts & Sciences. "It turns out it does make ...

Beaumont research finds advanced CT scanners reduce patient radiation exposure

2014-06-20

Computed tomography scans are an accepted standard of care for diagnosing heart and lung conditions. But clinicians worry that the growing use of CT scans could be placing patients at a higher lifetime risk of cancer from radiation exposure.

Beaumont Health System research, published in the June 20 online issue of the Journal of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, found that the use of advanced CT scanning equipment is helping to address this important concern.

The study, of 2,085 patients at nine centers in the U.S. and Middle East, found that using newer generation, ...

Inner ear stem cells hold promise for restoring hearing

2014-06-20

New Rochelle, NY, June 20, 2014—Spiral ganglion cells are essential for hearing and their irreversible degeneration in the inner ear is common in most types of hearing loss. Adult spiral ganglion cells are not able to regenerate. However, new evidence in a mouse model shows that spiral ganglion stem cells present in the inner ear are capable of self-renewal and can be grown and induced to differentiate into mature spiral ganglion cells as well as neurons and glial cells, as described in an article in BioResearch Open Access, a peer-reviewed journal from Mary Ann Liebert, ...