(Press-News.org) Cambridge, Mass. – June 25, 2014 – In wind farms across North America and Europe, sleek turbines equipped with state-of-the-art technology convert wind energy into electric power. But tucked inside the blades of these feats of modern engineering is a decidedly low-tech core material: balsa wood.

Like other manufactured products that use sandwich panel construction to achieve a combination of light weight and strength, turbine blades contain carefully arrayed strips of balsa wood from Ecuador, which provides 95 percent of the world's supply.

For centuries, the fast-growing balsa tree has been prized for its light weight and stiffness relative to density. But balsa wood is expensive and natural variations in the grain can be an impediment to achieving the increasingly precise performance requirements of turbine blades and other sophisticated applications.

As turbine makers produce ever-larger blades—the longest now measure 75 meters, almost matching the wingspan of an Airbus A380 jetliner—they must be engineered to operate virtually maintenance-free for decades. In order to meet more demanding specifications for precision, weight, and quality consistency, manufacturers are searching for new sandwich construction material options.

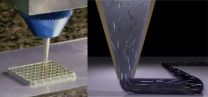

Now, using a cocktail of fiber-reinforced epoxy-based thermosetting resins and 3D extrusion printing techniques, materials scientists at the Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS) and the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering have developed cellular composite materials of unprecedented light weight and stiffness. Because of their mechanical properties and the fine-scale control of fabrication, the researchers say these new materials mimic and improve on balsa, and even the best commercial 3D-printed polymers and polymer composites available.

A paper describing their results has been published online in the journal Advanced Materials.

Until now, 3D printing has been developed for thermo plastics and UV-curable resins—materials that are not typically considered as engineering solutions for structural applications. "By moving into new classes of materials like epoxies, we open up new avenues for using 3D printing to construct lightweight architectures," says principal investigator Jennifer A. Lewis, the Hansjörg Wyss Professor of Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard SEAS. "Essentially, we are broadening the materials palate for 3D printing."

"Balsa wood has a cellular architecture that minimizes its weight since most of the space is empty and only the cell walls carry the load. It therefore has a high specific stiffness and strength," explains Lewis, who in addition to her role at Harvard SEAS is also a Core Faculty Member at the Wyss Institute. "We've borrowed this design concept and mimicked it in an engineered composite."

Lewis and Brett G. Compton, a former postdoctoral fellow in her group, developed inks of epoxy resins, spiked with viscosity-enhancing nanoclay platelets and a compound called dimethyl methylphosphonate, and then added two types of fillers: tiny silicon carbide "whiskers" and discrete carbon fibers. Key to the versatility of the resulting fiber-filled inks is the ability to control the orientation of the fillers.

The direction that the fillers are deposited controls the strength of the materials (think of the ease of splitting a piece of firewood lengthwise versus the relative difficulty of chopping on the perpendicular against the grain).

Lewis and Compton have shown that their technique yields cellular composites that are as stiff as wood, 10 to 20 times stiffer than commercial 3D-printed polymers, and twice as strong as the best printed polymer composites. The ability to control the alignment of the fillers means that fabricators can digitally integrate the composition, stiffness, and toughness of an object with its design.

"This paper demonstrates, for the first time, 3D printing of honeycombs with fiber-reinforced cell walls," said Lorna Gibson, a professor of materials science and mechanical engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and one of world's leading experts in cellular composites, who was not involved in this research. "Of particular significance is the way that the fibers can be aligned, through control of the fiber aspect ratio—the length relative to the diameter—and the nozzle diameter. This marks an important step forward in designing engineering materials that mimic wood, long known for its remarkable mechanical properties for its weight."

"As we gain additional levels of control in filler alignment and learn how to better integrate that orientation into component design, we can further optimize component design and improve materials efficiency," adds Compton, who is now a staff scientist in additive manufacturing at Oak Ridge National Laboratory. "Eventually, we will be able to use 3D printing technology to change the degree of fiber filler alignment and local composition on the fly."

The work could have applications in many fields, including the automotive industry where lighter materials hold the key to achieving aggressive government-mandated fuel economy standards. According to one estimate, shedding 110 pounds from each of the 1 billion cars on the road worldwide could produce $40 billion in annual fuel savings.

3D printing has the potential to radically change manufacturing in other ways too. Lewis says the next step will be to test the use of thermosetting resins to create different kinds of architectures, especially by exploiting the technique of blending fillers and precisely aligning them. This could lead to advances not only in structural materials, but also in conductive composites.

Previously, Lewis has conducted groundbreaking research in the 3D printing of tissue constructs with vasculature and lithium-ion microbatteries.

INFORMATION:

Primary support for the cellular composites work came from the BASF North American Center for Research on Advanced Materials at Harvard.

Additional support was provided by the Materials Research Science and Engineering Center at Harvard, funded by the National Science Foundation (DMR 0820484).

About the Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences

The Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS) serves as the connector and integrator of Harvard's teaching and research efforts in engineering, applied sciences, and technology. Through collaboration with researchers from all parts of Harvard, other universities, and corporate and foundational partners, we bring discovery and innovation directly to bear on improving human life and society. For more information, visit: http://seas.harvard.edu.

About the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University

The Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University uses Nature's design principles to develop bioinspired materials and devices that will transform medicine and create a more sustainable world. Working as an alliance among all of Harvard's Schools, and in partnership with Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston Children's Hospital, Dana Farber Cancer Institute, Massachusetts General Hospital, the University of Massachusetts Medical School, Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital, Boston University, Tufts University, Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin, and the University of Zurich, the Institute crosses disciplinary and institutional barriers to engage in high-risk research that leads to transformative technological breakthroughs. By emulating Nature's principles for self-organizing and self-regulating, Wyss researchers are developing innovative new engineering solutions for healthcare, energy, architecture, robotics, and manufacturing. These technologies are translated into commercial products and therapies through collaborations with clinical investigators, corporate alliances, and new start-ups.

Carbon-fiber epoxy honeycombs mimic the material performance of balsa wood

Harvard engineers use new resin inks and 3D printing to construct lightweight cellular composites

2014-06-25

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Changes in forage fish abundance alter Atlantic cod distribution, affect fishery success

2014-06-25

A shift in the prey available to Atlantic cod in the Gulf of Maine that began nearly a decade ago contributed to the controversy that surrounded the 2011 assessment for this stock. A recent study of how this occurred may help fishery managers, scientists, and the industry understand and resolve apparent conflicts between assessment results and the experiences of the fishing industry.

When the dominant prey species of Atlantic cod changed from Atlantic herring to sand lance beginning in 2006, cod began to concentrate in a small area on Stellwagen Bank where they were easily ...

New insights for coping with personality changes in acquired brain injury

2014-06-25

Amsterdam, NL, June 25, 2014 – Individuals with brain injury and their families often struggle to accept the associated personality changes. The behavior of individuals with acquired brain injury (ABI) is typically associated with problems such as aggression, agitation, non-compliance, and depression. Treatment goals often focus on changing the individual's behavior, frequently using consequence-based procedures or medication. In the current issue of NeuroRehabilitation leading researchers challenge this approach and recommend moving emphasis from dysfunction to competence. ...

People with tinnitus process emotions differently from their peers, researchers report

2014-06-25

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — Patients with persistent ringing in the ears – a condition known as tinnitus – process emotions differently in the brain from those with normal hearing, researchers report in the journal Brain Research.

Tinnitus afflicts 50 million people in the United States, according to the American Tinnitus Association, and causes those with the condition to hear noises that aren't really there. These phantom sounds are not speech, but rather whooshing noises, train whistles, cricket noises or whines. Their severity often varies day to day.

University of Illinois ...

New math technique improves atomic property predictions to historic accuracy

2014-06-25

By combining advanced mathematics with high-performance computing, scientists at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and Indiana University (IU) have developed a tool that allowed them to calculate a fundamental property of most atoms on the periodic table to historic accuracy—reducing error by a factor of a thousand in many cases. The technique also could be used to determine a host of other atomic properties important in fields like nuclear medicine and astrophysics.*

NIST's James Sims and IU's Stanley Hagstrom have calculated the base energy levels ...

Study: Motivational interviewing helps reduce home secondhand smoke exposure

2014-06-25

A Johns Hopkins-led research team has found that motivational interviewing, along with standard education and awareness programs, significantly reduced secondhand smoke exposure among children living in those households.

Motivational interviewing, a counseling strategy that gained popularity in the treatment of alcoholics, uses a patient-centered counseling approach to help motivate people to change behaviors. Experts say it stands in contrast to externally driven tactics, instead favoring to work with patients by acknowledging how difficult change is and by helping people ...

MicroRNA that blocks bone destruction could offer new therapeutic target for osteoporosis

2014-06-25

DALLAS – June 25, 2014 – UT Southwestern cancer researchers have identified a promising molecule that blocks bone destruction and, therefore, could provide a potential therapeutic target for osteoporosis and bone metastases of cancer.

The molecule, miR-34a, belongs to a family of small molecules called microRNAs (miRNAs) that serve as brakes to help regulate how much of a protein is made, which in turn, determines how cells respond.

UT Southwestern researchers found that mice with higher than normal levels of miR-34a had increased bone mass and reduced bone breakdown. ...

First positive results toward a therapeutic vaccine against brain cancer

2014-06-25

Astrocytomas and oligodendrogliomas are subtypes of a brain cancer called 'glioma'. These incurable brain tumors arise from glial cells, a type of support cell found in the central nervous system. "Low-grade gliomas", which grow comparatively slowly, spread in a diffuse manner across the brain and are very difficult to completely eliminate through surgery. In many cases, the effectiveness of treatments with chemotherapy and radiotherapy is very limited. Gliomas can develop into extremely aggressive glioblastomas.

Low-grade gliomas have a particular feature in common: ...

Natural resources worth more than US$40 trillion must be accounted for

2014-06-25

Natural resources worth more than US$40 Trillion must be accounted for

Governments and companies must do more to account for their impact and dependence on the natural environment - according to researchers at the University of East Anglia.

New research published today in the journal Nature Climate Change reveals that although some companies like Puma and Gucci are leading the way, more needs to be done to foster a sustainable green economy.

Researchers say that while the economic value of lost natural resources can be difficult to quantify, much more must be done ...

Kaiser Permanente paper: E-surveillance program targets care gaps in outpatient settings

2014-06-25

PASADENA, Calif., June 25, 2014 — An innovative framework for identifying and addressing potential gaps in health care in outpatient settings using electronic clinical surveillance tools has been used to target patient safety across a variety of conditions, according to a study published today in the journal eGEMs.

The Kaiser Permanente Southern California Outpatient Safety Net Program (OSNP) leverages the power of electronic health records as well as a proactive clinical culture to scan for potential quality improvement opportunities and intervene to improve patient ...

Obesity before pregnancy linked to earliest preterm births, Stanford/Packard study finds

2014-06-25

Women who are obese before they become pregnant face an increased risk of delivering a very premature baby, according to a new study of nearly 1 million California births.

The findings from the Stanford University School of Medicine provide important clues as to what triggers extremely preterm births, specifically those that occur prior to 28 weeks of pregnancy.

The study, published in the July issue of Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology, found no link between maternal obesity and premature births that happen between 28 and 37 weeks of the normal 40-week gestation ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Genomics offers a faster path to restoring the American chestnut

Caught in the act: Astronomers watch a vanishing star turn into a black hole

Why elephant trunk whiskers are so good at sensing touch

A disappearing star quietly formed a black hole in the Andromeda Galaxy

Yangtze River fishing ban halts 70 years of freshwater biodiversity decline

Genomic-informed breeding approaches could accelerate American chestnut restoration

How plants control fleshy and woody tissue growth

Scientists capture the clearest view yet of a star collapsing into a black hole

New insights into a hidden process that protects cells from harmful mutations

Yangtze River fishing ban halts seven decades of biodiversity decline

Researchers visualize the dynamics of myelin swellings

Cheops discovers late bloomer from another era

Climate policy support is linked to emotions - study

New method could reveal hidden supermassive black hole binaries

Novel AI model accurately detects placenta accreta in pregnancy before delivery, new research shows

Global Physics Photowalk winners announced

Exercise trains a mouse's brain to build endurance

New-onset nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy and initiators of semaglutide in US veterans with type 2 diabetes

Availability of higher-level neonatal care in rural and urban US hospitals

Researchers identify brain circuit and cells that link prior experiences to appetite

Frog love songs and the sounds of climate change

Hunter-gatherers northwestern Europe adopted farming from migrant women, study reveals

Light-based sensor detects early molecular signs of cancer in the blood

3D MIR technique guides precision treatment of kids’ heart conditions

Which childhood abuse survivors are at elevated risk of depression? New study provides important clues

Plants retain a ‘genetic memory’ of past population crashes, study shows

CPR skills prepare communities to save lives when seconds matter

FAU study finds teen ‘sexting’ surge, warns of sextortion and privacy risks

Chinese Guidelines for Clinical Diagnosis, Treatment, and Management of Cirrhosis (2025)

Insilico Medicine featured in Harvard Business School case on Rentosertib

[Press-News.org] Carbon-fiber epoxy honeycombs mimic the material performance of balsa woodHarvard engineers use new resin inks and 3D printing to construct lightweight cellular composites