(Press-News.org) The impact of the greenhouse gas CO2 on the Earth's temperature is well established by climate models and temperature records over the past 100 years, as well as coupled records of carbon dioxide concentration and temperature throughout Earth history. However, past temperature records have suggested that warming is largely confined to mid-to-high latitudes, especially the poles, whereas tropical temperatures appear to be relatively stable: the tropical thermostat model.

The new results, published today in Nature Geoscience, contradict those previous studies and indicate that tropical sea surface temperatures were warmer during the early-to-mid Pliocene, an interval spanning about 5 to 3 million years ago.

The Pliocene is of particular interest because CO2 concentrations then were thought to have been about 400 parts per million, the highest level of the past 5 million years but a level that was reached for the first time last summer due to human activity. The higher CO2 levels of the Pliocene have long been associated with a warmer world, but evidence from tropical regions suggested relatively stable temperatures.

Project leader and Director of the Cabot Institute, Professor Richard Pancost said: "These results confirm what climate models have long predicted – that although greenhouse gases cause greater warming at the poles they also cause warming in the tropics. Such findings indicate that few places on Earth will be immune to global warming and that the tropics will likely experience associated climate impacts, such as increased tropical storm intensity."

The scientists focussed their attention on the South China Sea which is at the fringe of a vast warm body of water, the West Pacific Warm Pool (WPWP). Some of the most useful temperature proxies are insensitive to temperature change in the heart of the WPWP, which is already at the maximum temperature they can record. By focussing on the South China Sea, the researchers were able to use a combination of geochemical records to reconstruct sea surface temperature in the past.

Not all of the records agree, however, and the researchers argue that certain tools used for reconstructing past ocean temperatures should be re-evaluated.

The paper's first author, Charlotte O'Brien added: "It's challenging to reconstruct the temperatures of the ocean many millions of years ago, and each of the tools we use has its own set of limitations. That is why we have used a combination of approaches in this investigation. We have shown that two different approaches agree – but a third approach agrees only if we make some assumptions about how the magnesium and calcium content of seawater has changed over the past 5 million years. That is an assumption that now needs to be tested."

The work was funded by the UK's Natural Environment Research Council and is ongoing.

Dr Gavin Foster at the University of Southampton is particularly interested in coupling the temperature records with improved estimates of Pliocene carbon dioxide levels. He said: "Just as we continue to challenge our temperature reconstructions we must challenge the corresponding carbon dioxide estimates. Together, they will help us truly understand the natural sensitivity of the Earth system and provide a better framework for predicting future climate change."

INFORMATION: END

High CO2 levels cause warming in the tropics

2014-06-29

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Single-pixel 'multiplex' captures elusive terahertz images

2014-06-29

CHESTNUT HILL, MA (June 29, 2014) – A novel metamaterial enables a fast, efficient and high-fidelity terahertz radiation imaging system capable of manipulating the stubborn electromagnetic waves, advancing a technology with potential applications in medical and security imaging, a team led by Boston College researchers reports in the online edition of the journal Nature Photonics.

The team reports it developed a "multiplex" tunable spatial light modulator (SLM) that uses a series of filter-like "masks" to retrieve multiple samples of a terahertz (THz) scene, which are ...

Marine bacteria are natural source of chemical fire retardants

2014-06-29

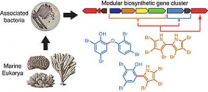

Researchers at the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine have discovered a widely distributed group of marine bacteria that produce compounds nearly identical to toxic man-made fire retardants.

Among the chemicals produced by the ocean-dwelling microbes, which have been found in habitats as diverse as sea grasses, marine sediments and corals, is a potent endocrine disruptor that mimics the human body's most active thyroid hormone.

The study is published in the June 29 online issue of Nature Chemical Biology.

"We find it very surprising and a tad alarming ...

NIH-funded researchers extend liver preservation for transplantation

2014-06-29

Researchers have developed a new supercooling technique to increase the amount of time human organs could remain viable outside the body. This study was conducted in rats, and if it succeeds in humans, it would enable a world-wide allocation of donor organs, saving more lives.

The research is supported by National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB) and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease (NIDDK), both parts of the National Institutes of Health.

The first human whole organ transplant 60 years ago—a living kidney ...

Massachusetts General-developed protocol could greatly extend preservation of donor livers

2014-06-29

A system developed by investigators at the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) Center for Engineering in Medicine allowed successful transplantation of rat livers after preservation for as long as four days, more than tripling the length of time organs currently can be preserved. The team describes their protocol – which combines below-freezing temperatures with the use of two protective solutions and machine perfusion of the organ – in a Nature Medicine paper receiving advance online publication.

"To our knowledge, this is the longest preservation time with subsequent ...

Reconstructing the life history of a single cell

2014-06-29

Researchers have developed new methods to trace the life history of individual cells back to their origins in the fertilised egg. By looking at the copy of the human genome present in healthy cells, they were able to build a picture of each cell's development from the early embryo on its journey to become part of an adult organ.

During the life of an individual, all cells in the body develop mutations, known as somatic mutations, which are not inherited from parents or passed on to offspring. These somatic mutations carry a coded record of the lifetime experiences of ...

Study finds Emperor penguin in peril

2014-06-29

An international team of scientists studying Emperor penguin populations across Antarctica finds the iconic animals in danger of dramatic declines by the end of the century due to climate change. Their study, published today in Nature Climate Change, finds the Emperor penguin "fully deserving of endangered status due to climate change."

The Emperor penguin is currently under consideration for inclusion under the US Endangered Species Act. Criteria to classify species by their extinction risk are based on the global population dynamics.

The study was conducted by lead ...

Noninvasive brain control

2014-06-29

CAMBRIDGE, MA -- Optogenetics, a technology that allows scientists to control brain activity by shining light on neurons, relies on light-sensitive proteins that can suppress or stimulate electrical signals within cells. This technique requires a light source to be implanted in the brain, where it can reach the cells to be controlled.

MIT engineers have now developed the first light-sensitive molecule that enables neurons to be silenced noninvasively, using a light source outside the skull. This makes it possible to do long-term studies without an implanted light source. ...

Bending the rules

2014-06-29

(Santa Barbara, Calif.) — For his doctoral dissertation in the Goldman Superconductivity Research Group at the University of Minnesota, Yu Chen, now a postdoctoral researcher at UC Santa Barbara, developed a novel way to fabricate superconducting nanocircuitry. However, the extremely small zinc nanowires he designed did some unexpected — and sort of funky — things.

Chen, along with his thesis adviser, Allen M. Goldman, and theoretical physicist Alex Kamenev, both of the University of Minnesota, spent years seeking an explanation for these extremely puzzling effects. ...

Improved method for isotope enrichment could secure a vital global commodity

2014-06-29

AUSTIN, Texas — Researchers at The University of Texas at Austin have devised a new method for enriching a group of the world's most expensive chemical commodities, stable isotopes, which are vital to medical imaging and nuclear power, as reported this week in the journal Nature Physics. For many isotopes, the new method is cheaper than existing methods. For others, it is more environmentally friendly.

A less expensive, domestic source of stable isotopes could ensure continuation of current applications while opening up opportunities for new medical therapies and fundamental ...

Improved survival with TAS-102 in mets colorectal cancer refractory to standard therapies

2014-06-28

The new combination agent TAS-102 is able to improve overall survival compared to placebo in patients whose metastatic colorectal cancer is refractory to standard therapies, researchers said at the ESMO 16th World Congress on Gastrointestinal Cancer in Barcelona.

"Around 50% of patients with colorectal cancer develop metastases but eventually many of them do not respond to standard therapies," said Takayuki Yoshino of the National Cancer Centre Hospital East in Chiba, Japan, lead author of the phase III RECOURSE trial. "The RECOURSE study shows that TAS-102 improves overall ...