(Press-News.org) UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. -- Malaria parasites alter the chemical odor signal of their hosts to attract mosquitos and better spread their offspring, according to researchers, who believe this scent change could be used as a diagnostic tool.

"Malaria-infected mice are more attractive to mosquitos than uninfected mice," said Mark Mescher, associate professor of entomology, Penn State. "They are the most attractive to these mosquito vectors when the disease is most transmissible."

Malaria in humans and animals is caused by parasites and can be spread only by an insect vector, a mosquito. The mosquito ingests the parasite with a blood meal, and the parasite creates the next generation in the mosquito's gut. These nascent parasites travel to the mosquito's salivary glands and are passed to the host during the next meal.

"We were most interested in individuals that are infected with the malaria parasite but are asymptomatic," said Consuelo De Moraes, professor of entomology, Penn State. "Asymptomatic people can still transmit the disease unless they are treated, so if we can identify them we may be able to better control the disease."

The researchers found that using a mouse malaria model, the mosquitos were more attracted to infected mice, even when the mice were otherwise asymptomatic. They report their findings today (June 30) in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The researchers, who also included Nina M. Stanczyk, former postdoctoral fellow; Heike S. Betz, research technologist, entomology; Hannier Pulido, graduate student in entomology; Derek G. Sim, technician, senior research assistant, biology; and Andrew F. Read, Alumni Professor in the Biological Sciences and Professor of Entomology, all of Penn State, also showed that several individual compounds whose concentrations were altered by malaria infection contributed to the increase in attractiveness to mosquitoes.

To eliminate other factors such as carbon dioxide production and body temperature as an attractant, the researchers extracted the body scent from the mice and showed that the changes in the scent alone altered the attraction of mosquitoes.

"Mosquitos wouldn't opt to carry the malaria parasite because it isn't good for the mosquito," said De Moraes. "Probably the parasite is not only manipulating the mice to alter their scent, but the mosquitos to be more attracted to the infected scent."

While the mosquitos were not attracted to mice that had acute malaria symptoms, they were particularly attracted to mice during a period of recovery when the transmissible stage of the malaria parasite was present at high levels.

In regions where malaria is prevalent, significant numbers of people harbor asymptomatic infections but remain able to transmit the disease to others. The researchers hope this altered scent profile might help to identify those needing treatment.

"If this holds true in humans, we may be able to screen humans for the chemical scent profile using this biomarker to identify carriers," said Mescher.

INFORMATION:

The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation Grand Challenges Exploration supported this work.

Malaria parasite manipulates host's scent

2014-06-30

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Adults can undo heart disease risk

2014-06-30

CHICAGO --- The heart is more forgiving than you may think -- especially to adults who try to take charge of their health, a new Northwestern Medicine® study has found.

When adults in their 30s and 40s decide to drop unhealthy habits that are harmful to their heart and embrace healthy lifestyle changes, they can control and potentially even reverse the natural progression of coronary artery disease, scientists found.

The study was published June 30 in the journal Circulation.

"It's not too late," said Bonnie Spring lead investigator of the study and a professor of ...

New Tel Aviv University research links Alzheimer's to brain hyperactivity

2014-06-30

Patients with Alzheimer's disease run a high risk of seizures. While the amyloid-beta protein involved in the development and progression of Alzheimer's seems the most likely cause for this neuronal hyperactivity, how and why this elevated activity takes place hasn't yet been explained – until now.

A new study by Tel Aviv University researchers, published in Cell Reports, pinpoints the precise molecular mechanism that may trigger an enhancement of neuronal activity in Alzheimer's patients, which subsequently damages memory and learning functions. The research team, led ...

Study helps unlock mystery of high-temp superconductors

2014-06-30

A Binghamton University physicist and his colleagues say they have unlocked one key mystery surrounding high-temperature superconductivity. Their research, published this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, found a remarkable phenomenon in copper-oxide (cuprate) high-temperature superconductors.

Michael Lawler, assistant professor of physics at Binghamton, is part of an international team of physicists with an ongoing interest in the mysterious pseudogap phase, the phase situated between insulating and superconducting phases in the cuprate phase ...

Tropical countries' growing wealth may aid conservation

2014-06-30

DURHAM, N.C. -- While inadequate funding has hampered international efforts to conserve biodiversity in tropical forests, a new Duke University-led study finds that people in a growing number of tropical countries may be willing to shoulder more of the costs on their own.

"In wealthier developing countries, there has been a significant increase in public demand for conservation, which has not yet been matched by an equivalent increase in protective actions by the governments of those countries," said Jeffrey R. Vincent, a Duke environmental economist who led the study, ...

Using geometry, researchers coax human embryonic stem cells to organize themselves

2014-06-30

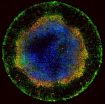

About seven days after conception, something remarkable occurs in the clump of cells that will eventually become a new human being. They start to specialize. They take on characteristics that begin to hint at their ultimate fate as part of the skin, brain, muscle or any of the roughly 200 cell types that exist in people, and they start to form distinct layers.

Although scientists have studied this process in animals, and have tried to coax human embryonic stem cells into taking shape by flooding them with chemical signals, until now the process has not been successfully ...

Research team pursues techniques to improve elusive stem cell therapy

2014-06-30

Stem cell scientists had what first appeared to be an easy win for regenerative medicine when they discovered mesenchymal stem cells several decades ago. These cells, found in the bone marrow, can give rise to bone, fat, and muscle tissue, and have been used in hundreds of clinical trials for tissue repair. Unfortunately, the results of these trials have been underwhelming. One problem is that these stem cells don't stick around in the body long enough to benefit the patient.

But Harvard Stem Cell Institute (HSCI) scientists at Boston Children's Hospital aren't ready ...

Oil palm plantations threaten water quality, Stanford scientists say

2014-06-30

If you've gone grocery shopping lately, you've probably bought palm oil.

Found in thousands of products, from peanut butter and packaged bread to shampoo and shaving cream, palm oil is a booming multibillion-dollar industry. While it isn't always clearly labeled in supermarket staples, the unintended consequences of producing this ubiquitous ingredient have been widely publicized.

The clearing of tropical forests to plant oil palm trees releases massive amounts of carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas fueling climate change. Converting diverse forest ecosystems to these ...

New study: Ancient Arctic sharks tolerated brackish water 50 million years ago

2014-06-30

Sharks were a tolerant bunch some 50 million years ago, cruising an Arctic Ocean that contained about the same percentage of freshwater as Louisiana's Lake Ponchatrain does today, says a new study involving the University of Colorado Boulder and the University of Chicago.

The study indicates the Eocene Arctic sand tiger shark, a member of the lamniform group of sharks that includes today's great white, thresher and mako sharks, was thriving in the brackish water of the western Arctic Ocean back then. In contrast, modern sand tiger sharks living today in the Atlantic Ocean ...

First pediatric autism study conducted entirely online

2014-06-30

UC San Francisco researchers have completed the first Internet-based clinical trial for children with autism, establishing it as a viable and cost effective method of conducting high-quality and rapid clinical trials in this population.

In their study, published in the June 2014 issue of the Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, the researchers looked at whether an Internet-based trial was a feasible way to evaluate whether omega-3 fatty acids helped reduce hyperactivity in children with autism. The authors found that not only was it a valuable ...

Research proves shock wave from explosives causes significant eye damage

2014-06-30

Researchers at The University of Texas at San Antonio (UTSA) are discovering that the current protective eyewear used by our U.S. armed forces might not be adequate to protect soldiers exposed to explosive blasts.

According to a recent study, ocular injuries now account for 13 percent of all battlefield injuries and are the fourth most common military deployment-related injury.

With the support of the U.S. Department of Defense, UTSA biomedical engineering assistant professor Matthew Reilly and distinguished senior lecture in geological sciences Walter Gray have been ...