(Press-News.org) CORVALLIS, Ore. – The oxygen-rich surface waters of the world's major oceans are supersaturated with methane – a powerful greenhouse gas that is roughly 20 times more potent than carbon dioxide – yet little is known about the source of this methane.

Now a new study by researchers at Oregon State University demonstrates the ability of some strains of the oceans' most abundant organism – SAR11 – to generate methane as a byproduct of breaking down a compound for its phosphorus.

Results of the study are being published this week in Nature Communications. It was funded by the National Science Foundation and the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation.

"Anaerobic methane biogenesis was the only process known to produce methane in the oceans and that requires environments with very low levels of oxygen," said Angelicque "Angel" White, a researcher in OSU's College of Earth, Ocean, and Atmospheric Sciences and co-author on the study. "In the vast central gyres of the Pacific and Atlantic oceans, the surface waters have lots of oxygen from mixing with the atmosphere – and yet they also have lots of methane, hence the term 'marine methane paradox.'

"We've now learned that certain strains of SAR11, when starved for phosphorus, turn to a compound known as methylphosphonic acid," White added. "The organisms produce enzymes that can break this compound apart, freeing up phosphorus that can be used for growth – and leaving methane behind."

The discovery is an important piece of the puzzle in understanding the Earth's methane cycle, scientists say. It builds on a series of studies conducted by researchers from several institutions around the world over the past several years.

Previous research has shown that adding methylphosphonic acid, or MPn, to seawater produces methane, though no one knew exactly how. Then a laboratory study led by David Karl of the University of Hawaii and OSU's White found that an organism called Trichodesmium could break down MPn and thus it could be a potential source of phosphorus, which is a critical mineral essential to every living organism.

However, Trichodesmium are rare in the marine environment and unlikely to be the only source for vast methane deposits in the surface waters.

So White turned to Steve Giovannoni, a distinguished professor of microbiology at OSU, who not only maintains the world's largest bank of SAR11 strains, but who also discovered and identified SAR11 in 1990. In a series of experiments, White, Giovannoni, and graduate students Paul Carini and Emily Campbell tested the capacity of different SAR11 strains to consume MPn and cleave off methane.

"We found that some did produce a methane byproduct, and some didn't," White said. "Just as some humans have a different capacity for breaking down compounds for nutrition than others, so do these organisms. The bottom line is that this shows phosphate-starved bacterioplankton have the capability of producing methane and doing so in oxygen-rich waters."

SAR11 is the smallest free-living cell known and also has the smallest genome, or genetic structure, of any independent cell. Yet it dominates life in the oceans, thrives where most other cells would die, and plays a huge role in the cycling of carbon on Earth.

These bacteria are so dominant that their combined weight exceeds that of all the fish in the world's oceans, scientists say. In a marine environment that's low in nutrients and other resources, they are able to survive and replicate in extraordinary numbers – a milliliter of seawater, for instance, might contain 500,000 of these cells.

"The ocean is a competitive environment and these bacteria apparently won the race," said Giovannoni, a professor in OSU's College of Science. "Our analysis of the SAR11 genome indicates that they became the dominant life form in the oceans largely by being the simplest."

"Their ability to cleave off methane is an interesting finding because it provides a partial explanation for why methane is so abundant in the high-oxygen waters of the mid-ocean regions," Giovannoni added. "Just how much they contribute to the methane budget still needs to be determined."

Since the discovery of SAR11, scientists have been interested in their role in the Earth's carbon budget. Now their possible implication in methane creation gives the study of these bacteria new importance.

INFORMATION:

SAR11, oceans' most abundant organism, has ability to create methane

2014-07-07

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

EARTH Magazine: Preserving Peru's petrified forest

2014-07-07

Alexandria, Va. — Tucked high in the Andes Mountains of northern Peru is a remarkable fossil locality: a 39-million-year-old petrified forest preserved in nearly pristine condition: stumps, full trees, leaves and all. With its existence unknown to scientists until the early 1990s — and its significance unbeknownst to villagers — this ancient forest hosts the remains of more than 40 types of trees, some still rooted, that flourished in a lowland tropical forest until they were suddenly buried by a volcanic eruption during the Eocene.

Since its discovery a little more than ...

New study of largely unstudied mesophotic coral reef geology

2014-07-07

MIAMI – A new study on biological erosion of mesophotic tropical coral reefs, which are low energy reef environments between 30-150 meters deep, provides new insights into processes that affect the overall structure of these important ecosystems. The purpose of the study was to better understand how bioerosion rates and distribution of bioeroding organisms, such as fish, mollusks and sponges, differ between mesophotic reefs and their shallow-water counterparts and the implications of those variations on the sustainability of the reef structure.

Due to major advancements ...

Discovery of Neandertal trait in ancient skull raises new questions about human evolution

2014-07-07

Re-examination of a circa 100,000-year-old archaic early human skull found 35 years ago in Northern China has revealed the surprising presence of an inner-ear formation long thought to occur only in Neandertals.

"The discovery places into question a whole suite of scenarios of later Pleistocene human population dispersals and interconnections based on tracing isolated anatomical or genetic features in fragmentary fossils," said study co-author Erik Trinkaus, PhD, a physical anthropology professor at Washington University in St. Louis.

"It suggests, instead, that ...

Bruce Museum scientist identifies world's largest-ever flying bird

2014-07-07

GREENWICH, CT, EMBARGOED UNTIL JULY 7, 2014 (3:00 PM EST) -- Scientists have identified the fossilized remains of an extinct giant bird that is likely to have the largest wingspan of any bird ever to have lived. A paper announcing the findings, "Flight Performance of the Largest Volant Bird," was published July 7 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, and is authored by Dr. Daniel Ksepka, the newest Curator of Science at the Bruce Museum in Greenwich.

With a wingspan of 20 to 24 feet, Pelagornis sandersi was more than twice as big as the Royal ...

Scientist identifies world's biggest-ever flying bird

2014-07-07

DURHAM, N.C. -- Scientists have identified the fossilized remains of an extinct giant bird that could be the biggest flying bird ever found. With an estimated 20-24-foot wingspan, the creature surpassed size estimates based on wing bones from the previous record holder -- a long-extinct bird named Argentavis magnificens -- and was twice as big as the Royal Albatross, the largest flying bird today. Scheduled to appear online the week of July 7, 2014, in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the findings show that the creature was an extremely efficient ...

Mathematical model illustrates our online 'copycat' behavior

2014-07-07

Researchers from the University of Oxford, the University of Limerick, and the Harvard School of Public Health have developed a mathematical model to examine online social networks, in particular the trade-off between copying our friends and relying on 'best-seller' lists.

The researchers examined how users are influenced in the choice of apps that they install on their Facebook pages by creating a mathematical model to capture the dynamics at play. By incorporating data from the installation of Facebook apps into their mathematical model, they found that users selected ...

Time of day crucial to accurately test for diseases, new research finds

2014-07-07

A new study published today in the journal PNAS (Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences), has found that time of day and sleep deprivation have a significant effect on our metabolism. The finding could be crucial when looking at the best time of day to test for diseases such as cancer and heart disease, and for administering medicines effectively.

Researchers from the University of Surrey and The Institute of Cancer Research, London, investigated the links between sleep deprivation, body clock disruption and metabolism, and discovered a clear variation in metabolism ...

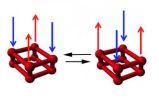

The quantum dance of oxygen

2014-07-07

Perhaps not everyone knows that oxygen has – quite unusually for such a simple molecule – magnetic properties. The phase diagram of solid oxygen at low temperatures and high pressures shows, however, several irregularities (for example, proper "information gaps" with regard to these magnetic properties) that are still poorly understood. A team of researchers from the International School for Advanced Studies (SISSA) and International Centre for Theoretical Physics Abdus Salam (ICTP) of Trieste, while trying to understand the origin of these phenomena, have identified a ...

DNA of 'Evolution Canyon' fruit flies reveals drivers of evolutionary change

2014-07-07

Scientists have long puzzled over the genetic differences between fruit flies that live hardly a puddle jump apart in a natural environment known as "Evolution Canyon" in Mount Carmel, Israel.

Now, an international team of researchers led by scientists with the Virginia Bioinformatics Institute at Virginia Tech has peered into the DNA of these closely related flies to discover how these animals have been able to adapt and survive in such close, but extremely different, ecologies.

One reason lies in a startling abundance of repetitive DNA elements that, until recently, ...

High earners in a stock market game have brain patterns that can predict market bubbles

2014-07-07

If you're so smart, why aren't you rich? It may be that, when it comes to stock market success, your brain is heeding the wrong neural signals.

In a study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences this week, scientists at the Virginia Tech Carilion Research Institute and Caltech found that, when they simulated market conditions for groups of investors, economic bubbles — in which the price of something could differ greatly from its actual value — invariably formed.

Even more remarkably, the researchers discovered a correlation between specific brain activity ...