(Press-News.org) MADISON, Wis. — The ability to reliably and safely make in the laboratory all of the different types of cells in human blood is one key step closer to reality.

Writing today in the journal Nature Communications, a group led by University of Wisconsin-Madison stem cell researcher Igor Slukvin reports the discovery of two genetic programs responsible for taking blank-slate stem cells and turning them into both red and the array of white cells that make up human blood.

The research is important because it identifies how nature itself makes blood products at the earliest stages of development. The discovery gives scientists the tools to make the cells themselves, investigate how blood cells develop and produce clinically relevant blood products.

"This is the first demonstration of the production of different kinds of cells from human pluripotent stem cells using transcription factors," explains Slukvin, referencing the proteins that bind to DNA and control the flow of genetic information, which ultimately determines the developmental fate of undifferentiated stem cells.

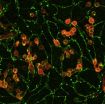

During development, blood cells emerge in the aorta, a major blood vessel in the embryo. There, blood cells, including hematopoietic stem cells, are generated by budding from a unique population of what scientists call hemogenic endothelial cells. The new report identifies two distinct groups of transcription factors that can directly convert human stem cells into the hemogenic endothelial cells, which subsequently develop into various types of blood cells.

The factors identified by Slukvin's group were capable of making the range of human blood cells, including white blood cells, red blood cells and megakaryocytes, commonly used blood products.

"By overexpressing just two transcription factors, we can, in the laboratory dish, reproduce the sequence of events we see in the embryo" where blood is made, says Slukvin of the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine in the UW School of Medicine and Public Health and the Wisconsin National Primate Research Center.

The method developed by Slukvin's group was shown to produce blood cells in abundance. For every million stem cells, the researchers were able to produce 30 million blood cells.

A critical aspect of the work is the use of modified messenger RNA to direct stem cells toward particular developmental fates. The new approach makes it possible to induce cells without introducing any genetic artifacts. By co-opting nature's method of making cells and avoiding all potential genetic artifacts, cells for therapy can be made safer.

"You can do it without a virus, and genome integrity is not affected," Slukvin notes.

Moreover, while the new work shows that blood can be made by manipulating genetic mechanisms, the approach is likely to be true as well for making other types of cells with therapeutic potential, including cells of the pancreas and heart.

An unfulfilled aspiration, says Slukvin, is to make hematopoietic stem cells, multipotent stem cells found in bone marrow. Hematopoietic stem cells are used to treat some cancers, including leukemia and multiple myeloma. Devising a method for producing them in the lab remains a significant challenge.

"We still don't know how to do that," Slukvin notes, "but our new approach to making blood cells will give us an opportunity to model their development in a dish and identify novel hematopoietic stem cell factors."

The study was conducted under the umbrella of the Progenitor Cell Biology Consortium, run by National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, part of the National Institutes of Health, and involved a collaboration of scientists at UW-Madison, the Morgridge Institute for Research, the University of Minnesota at the Twin Cities and the Houston Methodist Research Institute.

In addition to Slukvin, authors of the new report include Irina Elcheva, Vera Brok-Volchanskaya, Akhilesh Kumar, Patricia Liu, Jeong-Hee Lee, Lilian Tong and Maxim Vodyanik, all of the Wisconsin National Primate Research Center; Scott Swanson, Ron Stewart and James A. Thomson of the Morgridge Institute for Research; Michael Kyba of the University of Minnesota's Lillehei Heart Institute; and Eduard Yakubov and John Cooke of the Center for Cardiovascular Regeneration of the Houston Methodist Research Institute.

INFORMATION:

Terry Devitt, 608-262-8282, trdevitt@wisc.edu

The research underpinning the new Nature Communications report was supported by the National Institutes of Health, grant numbers U01HL099773, U01HL100407, U01HL099997 and P51 RR000167, and the Charlotte Geyer Foundation.

Wisconsin scientists find genetic recipe to turn stem cells to blood

2014-07-14

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Testicular cancer rates are on the rise in young Hispanic Americans

2014-07-14

A new analysis has found that rates of testicular cancer have been rising dramatically in recent years among young Hispanic American men, but not among their non-Hispanic counterparts. Published early online in Cancer, a peer-reviewed journal of the American Cancer Society, the findings indicate that greater awareness is needed concerning the increasing risk of testicular cancer in Hispanic adolescents and young adults, and that research efforts are needed to determine the cause of this trend.

Testicular cancer is one of the most common types of cancer among adolescent ...

Potential Alzheimer's disease risk factor and risk reduction strategies become clearer

2014-07-14

COPENHAGEN – Participation in activities that promote mental activity, and moderate physical activity in middle age, may help protect against the development of Alzheimer's disease and dementia in later life, according to new research reported today at the Alzheimer's Association International Conference® 2014 (AAIC® 2014) in Copenhagen.

Research reported at AAIC 2014 also showed that sleep problems – especially when combined with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) – may increase dementia risk in veterans. Additionally, in a population of people age 90 and older, ...

Weighty issue: Stress and high-fat meals combine to slow metabolism in women

2014-07-14

VIDEO:

Researchers at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center have found that women who ate a high-fat meal the day after a stressful event metabolized food more slowly, and the...

Click here for more information.

COLUMBUS, Ohio – A new study in women suggests that experiencing one or more stressful events the day before eating a single high-fat meal can slow the body's metabolism, potentially contributing to weight gain.

Researchers questioned study participants about ...

Prehistoric 'bookkeeping' continued long after invention of writing

2014-07-14

An archaeological dig in southeast Turkey has uncovered a large number of clay tokens that were used as records of trade until the advent of writing, or so it had been believed.

But the new find of tokens dates from a time when writing was commonplace – thousands of years after it was previously assumed this technology had become obsolete. Researchers compare it to the continued use of pens in the age of the word processor.

The tokens – small clay pieces in a range of simple shapes – are thought to have been used as a rudimentary bookkeeping system in prehistoric ...

The Lancet Neurology: Post-concussion 'return to play' decision for footballers should be made solely by doctors, says new editorial

2014-07-14

An editorial published today in The Lancet Neurology calls for sports authorities to take into consideration the long term neurological problems that repeated concussions can cause.

Cerebral concussion is the most common form of sports-related traumatic brain injury (TBI), and the long-term effects of repeated concussions may include dementia, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and other neurological disorders, say the journal editors.

However, what is perhaps more concerning, is that even when the symptoms of concussion are delayed, or if they come and go quickly, neurological ...

The Lancet Oncology: Differences in treatment likely to be behind differing survival rates for blood cancers between regions within Europe

2014-07-14

Failure to get the best treatment and variations in the quality of care are the most likely reasons why survival for blood cancer patients still varies widely between regions within Europe, according to the largest population-based study of survival in European adults to date, published in The Lancet Oncology.

"The good news is that 5-year survival for most cancers of the blood has increased over the past 11 years, most likely reflecting the approval of new targeted drugs in the early 2000s such as rituximab for non-Hodgkin lymphoma and imatinib for chronic myeloid leukaemia", ...

MUHC researcher unveils novel treatment for a form of childhood blindness

2014-07-14

This news release is available in French.

Montreal, July 13, 2014 — An international research project, led by the Research Institute of the McGill University Health Centre (RI-MUHC) in Montreal, reports that a new oral medication is showing significant progress in restoring vision to patients with Leber congenital amaurosis (LCA). Until now, this inherited retinal disease that causes visual impairment ranging from reduced vision to complete blindness, has remained untreatable. The study is published today in the scientific journal The Lancet.

"This is the first ...

Australia drying caused by greenhouse gases

2014-07-13

NOAA scientists have developed a new high-resolution climate model that shows southwestern Australia's long-term decline in fall and winter rainfall is caused by increases in manmade greenhouse gas emissions and ozone depletion, according to research published today in Nature Geoscience.

"This new high-resolution climate model is able to simulate regional-scale precipitation with considerably improved accuracy compared to previous generation models," said Tom Delworth, a research scientist at NOAA's Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory in Princeton, N.J., who helped ...

Deep within spinach leaves, vibrations enhance efficiency of photosynthesis

2014-07-13

ANN ARBOR – Biophysics researchers at the University of Michigan have used short pulses of light to peer into the mechanics of photosynthesis and illuminate the role that molecule vibrations play in the energy conversion process that powers life on our planet.

The findings could potentially help engineers make more efficient solar cells and energy storage systems. They also inject new evidence into an ongoing "quantum biology" debate over exactly how photosynthesis manages to be so efficient.

Through photosynthesis, plants and some bacteria turn sunlight, water and ...

Researchers discover boron 'buckyball'

2014-07-13

PROVIDENCE, R.I. (Brown University) -- The discovery 30 years ago of soccer-ball-shaped carbon molecules called buckyballs helped to spur an explosion of nanotechnology research. Now, there appears to be a new ball on the pitch.

Researchers from Brown University, Shanxi University and Tsinghua University in China have shown that a cluster of 40 boron atoms forms a hollow molecular cage similar to a carbon buckyball. It's the first experimental evidence that a boron cage structure—previously only a matter of speculation—does indeed exist.

"This is the first time that ...