(Press-News.org) ANN ARBOR, Mich. — When a medical emergency strikes, our gut tells us to get to the nearest hospital quickly. But a new study suggests that busier emergency centers may actually give the best chance of surviving – especially for people suffering life-threatening medical crises.

In fact, the analysis finds that patients admitted to a hospital after an emergency had a 10 percent lower chance of dying in the hospital if they initially went to one of the nation's busiest emergency departments, compared with the least busy.

The risk of dying differed even more for patients with potentially fatal, time-sensitive conditions. People with sepsis had a 26 percent lower death rate at the busiest emergency centers compared with the least busy, even after the researchers adjusted for a range of patient and hospital characteristics. For lung failure patients, the difference was 22 percent. Even heart attack death rates differed.

The new findings, based on national data on 17.5 million emergency patients treated at nearly 3,000 hospitals, appear in an Annals of Emergency Medicine paper by a University of Michigan Medical School team. Using U-M Department of Emergency Medicine funding, they analyzed data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample database compiled by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

The authors calculate that if all emergency patients received the kind of care that the busiest emergency centers give, 24,000 fewer people would die each year.

"It's too early to say that based on these results, patients and first responders should change their decision about which hospital to choose in an emergency," says Keith Kocher, M.D., MPH, the lead author of the new study and a U-M Health System emergency physician. "But the bottom line is that emergency departments and hospitals perform differently, there really are differences in care and they matter."

This is the first time a relationship has been shown on a national, broad-based scale between the volume of emergency patients seen at a hospital and the chance those patients will survive their hospital stay.

With half of all hospital inpatients now entering via the emergency department, data and lessons from the best-performing hospitals could improve patients' chances of leaving any hospital alive. It could also help guide the development of regional systems for emergency care, and specific measures of emergency care quality that could be used to rate hospitals and spur them to perform better.

The "practice makes perfect" effect

In addition to survival for all patients admitted to the hospital from the emergency department, Kocher and his colleagues focused on eight high-risk, time-critical conditions. They were: Pneumonia, congestive heart failure, sepsis, the type of heart attack known as an acute myocardial infarction, stroke, respiratory failure, gastrointestinal bleeding and acute respiratory failure.

All require emergency providers to use a certain level of diagnostic skill and technology, and successful treatment depends on the ability of emergency and inpatient teams to deliver specialized treatment. All carry a death risk of at least 3 percent, and rank among the top 25 reasons emergency patients get admitted to a hospital.

For instance, sepsis, a body-wide crisis sparked by uncontrolled infection, requires careful diagnosis, rapid deployment of antibiotics, blood pressure support and constant monitoring.

The team looked at patients who sought emergency care between 2005 and 2009, and excluded those transferred to another emergency department or hospital, those admitted to observation units, and those seen at hospitals with less than 1,000 emergency patients admitted a year. They looked at deaths during the first two days of hospitalization, and during the entire hospitalization.

The findings mirror surgery studies by U-M teams and others: The higher the volume, or number, of patients a center treats, the better the outcomes – even after adjusting for complicating factors.

Those studies have led to recommendations that patients in need of certain operations should choose to go only to the highest-volume surgeons and hospitals. But emergency patients often don't make a choice in where they get their care – either due to great differences in distance, or the fact that an emergency medical team makes the choice in the ambulance.

So, Kocher says, the survival effect in emergency care may be due to many things – the experience of the diagnosing emergency physicians, the availability of specialists, the skill and staffing levels of emergency and inpatient teams, the technologies available at the hospital, the patients' own health and socioeconomic background, and the location and nature of the hospital. He and his colleagues adjusted for these factors as much as possible before calculating survival rates.

Their results don't give insights into why the differences in survival occur – but for the first time, they show that they occur, so that further research can probe deeper.

"The take-home message for patients is that you should still call 911 or seek the closest emergency care, because you don't know exactly what you're experiencing," says Kocher, an assistant professor of emergency medicine. "What makes one hospital better than another is still a black box, and emergency medicine is still in its infancy in terms of figuring that out. For those who study and want to improve emergency care, and post-emergency care, we hope these findings will inform the way we identify conditions in the pre-hospital setting, where we send patients, and what we do once they arrive at the emergency department and we admit them to an inpatient bed."

INFORMATION:

In addition to Kocher, the research team included former U-M emergency physicians and Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholars Adam Sharp, M.D., M.S., now at Kaiser Permanente Research, Kori Sauser, M.D., M.S., now at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, and Amber Sabbatini, M.D., MPH, now at the University of Washington, as well as current U-M emergency medicine lecturer Adrianne Haggins, M.D., M.S., who also was an RWJ scholar.

Kocher and Haggins are members of the U-M Institute for Healthcare Policy and Innovation.

Reference: Annals of Emergency Medicine, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2014.06.008

For the sickest emergency patients, death risk is lowest at busiest emergency centers

Study on association between emergency department volume & survival suggests opportunity for new ways to organize & rate care

2014-07-17

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Best anticoagulants after orthopedic procedures depends on type of surgery

2014-07-17

Current guidelines do not distinguish between aspirin and more potent blood thinners for protecting against blood clots in patients who undergo major orthopedic operations, leaving the decision up to individual clinicians. A new analysis published today in the Journal of Hospital Medicine provides much-needed information that summarizes existing studies about which medications are best after different types of surgery.

Every year, hundreds of thousands of Americans undergo major orthopedic surgery such as hip and knee replacements and hip fracture repairs. Patients undergoing ...

Findings suggest antivirals underprescribed for patients at risk for flu complications

2014-07-17

Patients likely to benefit the most from antiviral therapy for influenza were prescribed these drugs infrequently during the 2012-2013 influenza season, while antibiotics may have been overprescribed. Published in Clinical Infectious Diseases and now available online, the findings suggest more efforts are needed to educate clinicians about the appropriate use of antivirals and antibiotics in the outpatient setting.

Influenza is a significant cause of mortality and morbidity, resulting in more than 200,000 hospitalizations in the U.S. each year, on average. While annual ...

New view of Rainier's volcanic plumbing

2014-07-17

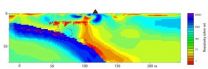

SALT LAKE CITY, July 17, 2014 – By measuring how fast Earth conducts electricity and seismic waves, a University of Utah researcher and colleagues made a detailed picture of Mount Rainier's deep volcanic plumbing and partly molten rock that will erupt again someday.

"This is the most direct image yet capturing the melting process that feeds magma into a crustal reservoir that eventually is tapped for eruptions," says geophysicist Phil Wannamaker, of the university's Energy & Geoscience Institute and Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering. "But it does not provide ...

Asthma drugs suppress growth

2014-07-17

Corticosteroid drugs that are given by inhalers to children with asthma may suppress their growth, evidence suggests. Two new systematic reviews published in The Cochrane Library focus on the effects of inhaled corticosteroid drugs (ICS) on growth rates. The authors found children's growth slowed in the first year of treatment, although the effects were minimised by using lower doses.

Inhaled corticosteroids are prescribed as first-line treatments for adults and children with persistent asthma. They are the most effective drugs for controlling asthma and clearly reduce ...

Niacin too dangerous for routine cholesterol therapy

2014-07-17

CHICAGO --- After 50 years of being a mainstay cholesterol therapy, niacin should no longer be prescribed for most patients due to potential increased risk of death, dangerous side effects and no benefit in reducing heart attacks and strokes, writes Northwestern Medicine® preventive cardiologist Donald Lloyd-Jones, M.D., in a New England Journal of Medicine editorial.

Lloyd-Jones's editorial is based on a large new study published in the journal that looked at adults, ages 50 to 80, with cardiovascular disease who took extended-release niacin (vitamin B3) and laropiprant ...

NIH scientists identify gene linked to fatal inflammatory disease in children

2014-07-17

Investigators have identified a gene that underlies a very rare but devastating autoinflammatory condition in children. Several existing drugs have shown therapeutic potential in laboratory studies, and one is currently being studied in children with the disease, which the researchers named STING-associated vasculopathy with onset in infancy (SAVI). The findings appeared online today in the New England Journal of Medicine. The research was done at the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS), part of the National Institutes of Health.

"Not ...

No-wait data centers

2014-07-17

Big websites usually maintain their own "data centers," banks of tens or even hundreds of thousands of servers, all passing data back and forth to field users' requests. Like any big, decentralized network, data centers are prone to congestion: Packets of data arriving at the same router at the same time are put in a queue, and if the queues get too long, packets can be delayed.

At the annual conference of the ACM Special Interest Group on Data Communication, in August, MIT researchers will present a new network-management system that, in experiments, reduced the average ...

Marginal life expectancy benefit from contralateral prophylactic mastectomy

2014-07-16

The choice of contralateral prophylactic mastectomy (CPM) by women with breast cancer (BC) diagnosed in one breast has recently increased in the US but may confer only a marginal life expectancy benefit depending on the type and stage of cancer, according to a study published July 16 in the JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

To assess the survival benefit of CPM, Pamela R. Portschy, of the Department of Surgery, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, and colleagues, developed a model simulating survival outcomes of CPM or no CPM for women with newly diagnosed ...

Screening costs increased in older women without changing detection rates of ESBC

2014-07-16

Medicare spending on breast cancer screening increased substantially between 2001 and 2009 but the detection rates of early stage tumors were unchanged, according to a new study published July 16 in the JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

The effect of introduction of new breast cancer screening modalities, such as digital images, computer-aided detection (CAD), and use of ultrasound and MRI on screening costs among older women is unknown, although women over the age of 65 represent almost one-third of the total women screened in the US annually. There is ...

Even mild traumatic brain injury may cause brain damage

2014-07-16

MINNEAPOLIS – Even mild traumatic brain injury may cause brain damage and thinking and memory problems, according to a study published in the July 16, 2014, online issue of Neurology®, the medical journal of the American Academy of Neurology.

For the study, 44 people with a mild traumatic brain injury and nine people with a moderate traumatic brain injury were compared to 33 people with no brain injury. All of the participants took tests of their thinking and memory skills. At the same time, they had diffusion tensor imaging scans, a type of MRI scan that is more sensitive ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

What makes healthy boundaries – and how to implement them – according to a psychotherapist

UK’s growing synthetic opioid problem: Nitazene deaths could be underestimated by a third

How rice plants tell head from toe during early growth

Scientists design solar-responsive biochar that accelerates environmental cleanup

Construction of a localized immune niche via supramolecular hydrogel vaccine to elicit durable and enhanced immunity against infectious diseases

Deep learning-based discovery of tetrahydrocarbazoles as broad-spectrum antitumor agents and click-activated strategy for targeted cancer therapy

DHL-11, a novel prieurianin-type limonoid isolated from Munronia henryi, targeting IMPDH2 to inhibit triple-negative breast cancer

Discovery of SARS-CoV-2 PLpro inhibitors and RIPK1 inhibitors with synergistic antiviral efficacy in a mouse COVID-19 model

Neg-entropy is the true drug target for chronic diseases

Oxygen-boosted dual-section microneedle patch for enhanced drug penetration and improved photodynamic and anti-inflammatory therapy in psoriasis

Early TB treatment reduced deaths from sepsis among people with HIV

Palmitoylation of Tfr1 enhances platelet ferroptosis and liver injury in heat stroke

Structure-guided design of picomolar-level macrocyclic TRPC5 channel inhibitors with antidepressant activity

Therapeutic drug monitoring of biologics in inflammatory bowel disease: An evidence-based multidisciplinary guidelines

New global review reveals integrating finance, technology, and governance is key to equitable climate action

New study reveals cyanobacteria may help spread antibiotic resistance in estuarine ecosystems

Around the world, children’s cooperative behaviors and norms converge toward community-specific norms in middle childhood, Boston College researchers report

How cultural norms shape childhood development

University of Phoenix research finds AI-integrated coursework strengthens student learning and career skills

Next generation genetics technology developed to counter the rise of antibiotic resistance

Ochsner Health hospitals named Best-in-State 2026

A new window into hemodialysis: How optical sensors could make treatment safer

High-dose therapy had lasting benefits for infants with stroke before or soon after birth

‘Energy efficiency’ key to mountain birds adapting to changing environmental conditions

Scientists now know why ovarian cancer spreads so rapidly in the abdomen

USF Health launches nation’s first fully integrated institute for voice, hearing and swallowing care and research

Why rethinking wellness could help students and teachers thrive

Seabirds ingest large quantities of pollutants, some of which have been banned for decades

When Earth’s magnetic field took its time flipping

Americans prefer to screen for cervical cancer in-clinic vs. at home

[Press-News.org] For the sickest emergency patients, death risk is lowest at busiest emergency centersStudy on association between emergency department volume & survival suggests opportunity for new ways to organize & rate care