(Press-News.org) State-of-the-art military hardware could soon fight malaria, one of the most deadly diseases on the planet.

Researchers at Monash University and the University of Melbourne have used an anti-tank Javelin missile detector, more commonly used in warfare to detect the enemy, in a new test to rapidly identify malaria parasites in blood.

Scientists say the novel idea, published in the journal Analysis, could set a new gold standard for malaria testing.

The technique is based on Fourier Transform Infrared (FITR) spectroscopy, which provides information on how molecules vibrate.

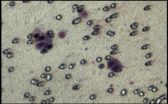

Researchers used a special detector known as a Focal Plane Array (FPA) to detect malaria parasite-infected red blood cells. Originally developed for Javelin anti-tank heat seeking missiles, the FPA gives highly detailed information on a sample area in minutes. The heat-seeking detector, which is coupled to an infrared imaging microscope, allowed the team to detect the earliest stages of the malaria parasite in a single red blood cell.

The infrared signature from the fatty acids of the parasites enabled the scientists to detect the parasite at an earlier stage, and crucially determine the number of parasites in a blood smear.

Lead researcher, Associate Professor Bayden Wood from Monash University said to reduce mortality and prevent the overuse of antimalarial drugs; a test that can catch malaria at its early stages is critical.

"Our test detects malaria at its very early stages, so that doctors can stop the disease in its tracks before it takes hold and kills. We believe this sets the gold standard for malaria testing," Associate Professor Wood said.

"There are some excellent tests that diagnose malaria. However, the sensitivity is limited and the best methods require hours of input from skilled microscopists, and that's a problem in developing countries where malaria is most prevalent," he said.

As well as being highly sensitive, the new test has a number of advantages – it gives an automatic diagnosis within four minutes, doesn't require a specialist technician and can detect the parasite in a single blood cell.

The disease, which is caused by the malaria parasite, kills 1.2 million people every year. Existing tests look for the parasite in a blood sample. However the parasites can be difficult to detect in the early stages of infection. As a result the disease is often spotted only when the parasites have developed and multiplied in the body.

Professor Leann Tilley from the University of Melbourne said the test could make an impact in large-scale screening of malaria parasite carriers who do not present the classic fever-type symptoms associated with the disease.

"In many countries only people who display signs of malaria are treated. But the problem with this approach is that some people don't have typical flu-like symptoms associated with malaria, and this means a reservoir of parasites persists that can reemerge and spread very quickly within a community," she said.

"Our test works because it can detect the malaria parasite at the very early stages and can reliably detect it is an automated manner in a single red blood cell. No other test can do that," Professor Tilley said.

FPA detectors were originally developed for Javelin Portable anti-tank missiles in the 1990s. The heat seeking detector is used on shoulder fired missiles but can also be installed on tracked, wheeled or amphibious vehicles, providing spatial and spectral information in a matter of seconds and are currently used by the defence force.

The FPA detector used in this project was coupled to a synchrotron source located at InfraRed Environmental Imaging (IRENI) facility at the Synchrotron Radiation Center (SRC) in Wisconsin, developed by Professor Carol Hirschmugl. The continued development of brighter laboratory based infrared sources along with optical refinements will see this type of technology make an enormous impact in the clinical environment.

The next phase of research will see Associate Professor Wood's team work with Professor Patcharee Jearanaikoon from the Kohn Kaen University in Thailand to test the new technology in hospital clinics.

INFORMATION:

Anti-tank missile detector joins the fight against malaria

2014-07-17

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Acupuncture and moxibustion reduces neuronal edema in Alzheimer's disease rats

2014-07-17

Aberrant Wnt signaling is possibly related to the pathological changes in Alzheimer's disease (AD). Axin and β-catenin protein is closely related to Wnt signaling. Zhou Hua and his team, Hubei University of Chinese Medicine, China confirmed that moxibustion or electroacupuncture, or both, at Baihui (GV20) and Shenshu (BL23) acupoints decreased axin protein expression, increased β-catenin protein expression, and alleviated neuronal cytoplasmic edema. These findings suggest that the mechanism underlying the neuroprotective effect of acupuncture in AD is associated ...

Who are responsible for protecting against neuron and synapse injury in immature rats?

2014-07-17

Fructose-1,6-diphosphate is a metabolic intermediate that promotes cell metabolism. Whether it can alleviate hippocampal neuronal injury caused by febrile convulsion remains unclear. Dr. Jianping Zhou, the Second Affiliated Hospital, Medical College of Xi'an Jiaotong University, China and his team established a repetitive febrile convulsion model in rats aged 21 days, equivalent to 3 years in humans, intraperitoneally administered fructose-1,6-diphosphate at 1,000 mg/kg into the rat model. Results showed that high-dose fructose-1,6-diphosphate reduced mitochondrial ...

Chemokine receptor 4 gene silencing blocks neuroblastoma metastasis in vitro

2014-07-17

Chemokine receptor 4 is a chemokine receptor that participates in tumor occurrence, growth and metastasis in vitro and its expression is upregulated during neuroblastoma metastasis. Dr. Xin Chen, the Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University, China successfully constructed chemokine receptor 4 sequence-specific small interfering RNA (siRNA) plasmids, transfected into SH-SY5Y cells and found that down-regulation of chemokine receptor 4 can inhibit in vitro invasion of neuroblastoma. This paper was published in Neural Regeneration Research (Vol. 9, No. 10, 2014).

Article: ...

Intrathecal bumetanide has analgesic effects through inhibition of NKCC1

2014-07-17

Accumulating evidence has demonstrated that the sodium-potassium-chloride co-transporter 1 (NKCC1) and potassium-chloride co-transporter 2 (KCC2) have a role in the modulation of pain transmission at the spinal level through chloride regulation in the pain pathway and by effecting neuronal excitability and pain sensitization. Dr. Yanbing He Zhujiang Hospital, Southern Medical University, China and his team found that intrathecal bumetanide could increase NKCC1 expression and decrease KCC2 expression in spinal cord neurons of rats with incisional pain. The authors presumed ...

Attenuated inhibition of neuron membrane excitability contributes to childhood depression

2014-07-17

Accumulating evidence suggests that the nucleus accumbens, which is involved in mechanisms of reward and addiction, plays a role in the pathogenesis of depression and in the action of antidepressants. Dandan Liu and her team, Bio-X Institute, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, China for the first time using electrophysiological method studied the signaling transduction pathway mediated by dopamine D2-like receptor in the medium spiny neurons in the core of the nucleus accumbens in the juvenile Wistar Kyoto rat model of depression. They concluded that impaired inhibition of ...

NYU research on persons w/ HIV/AIDS not taking medication and not engaged in care

2014-07-17

Regular attendance at HIV primary care visits and high adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART) are vital for people living with HIV/AIDS (PLHA), as these health behaviors lead to lowered rates of morbidity and mortality, increased quality of life, and reducing the risk of HIV transmission to others. However, a large proportion of PLHA in the United States are not sufficiently engaged in care and not taking ART when it is medically necessary.

A new study, "HIV-infected individuals who delay, decline, or discontinue antiretroviral therapy: Comparing clinic- and peer-recruited ...

Eradicating fatal sleeping sickness by killing off the tsetse fly

2014-07-17

A Brigham Young University ecologist is playing a role in the effort to curb a deadly disease affecting developing nations across equatorial Africa.

Steven L. Peck, a BYU professor of biology, has lent his expertise in understanding insect movement to help shape a UN-sanctioned eradication effort of the tsetse fly—a creature that passes the fatal African sleeping sickness to humans, domestic animals, and wildlife.

Using Peck's advanced computer models, crews from the UN's Food and Agriculture Organization will know where to concentrate their efforts to eliminate the ...

Investing in sexual and reproductive health of 10 to 14 year olds yields lifetime benefits

2014-07-17

WASHINGTON -- Age 10 to 14 years, a time when both girls and boys are constructing their own identities and are typically open to new ideas and influences, provides a unique narrow window of opportunity for parents, teachers, healthcare providers and others to facilitate transition into healthy teenage and adulthood years according to researchers from Georgetown University's Institute for Reproductive Health who note the lack worldwide of programs to help children of this age navigate passage from childhood to adulthood.

An estimated 1.2 billion adolescents live in the ...

Women's professional self-identity impacts on childcare balance, but not men's

2014-07-17

A new study finds that the more a woman self-identifies with her profession, the more paid hours she works and the less time she spends with the couple's children, but the more equal the childcare balance is between a couple.

However, the more a woman identifies herself with motherhood, the less time the father spends with the children.

And while the more a man self-identifies as a parent the more time he spends with children, this had no impact on the amount of time the woman spends on childcare – regardless of her self-identity.

The study, from Cambridge University's ...

Duck migration study reveals importance of conserving wetlands, MU researchers find

2014-07-17

COLUMBIA, Mo. – During the 2011 and 2012 migration seasons, University of Missouri researchers monitored mallard ducks with new remote satellite tracking technology, marking the first time ducks have been tracked closely during the entirety of their migration from Canada to the American Midwest and back. The research revealed that mallards use public and private wetland conservation areas extensively as they travel hundreds of miles across the continent. Dylan Kesler, an assistant professor of fisheries and wildlife in the College of Agriculture, Food and Natural Resources ...